Russell Brand Destroys America's Screwed Up View of Homelessness

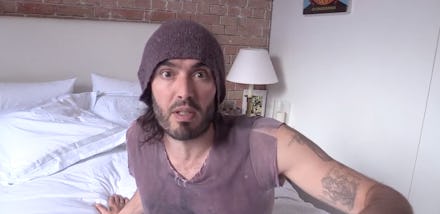

The news: When Fort Lauderdale police arrested a 90-year-old man for feeding the city's homeless, comedian Russell Brand recently decided to step in and speak out with a few choice words for the powers-that-be that made it happen.

"He couldn't look any more like an adorable old man, could he?" said Brand on Friday's episode of The Trews, Brand's daily YouTube web series. "And yet he's being ushered away by the police."

"These values now aren't the preserve of extreme activists, loonies in Anonymous masks tipping over police vans — they're the values of elderly old war veteran men, because the values we're talking about are just compassion and fairness."

"There's a prevailing idea that there's something ethically wrong with being poor, and that America's run according to Christian values. But when people are practicing genuine Christian values, they themselves are directly prosecuted ... [American businessmen] use Christianity and morality of all kind to protect their own corporate interests."

Brand accused businesses and corporations of promoting a "very popular current mentality" that brushes off the existence of vulnerable populations. "At no point do people think, 'We can divert some of this wealth and affluence at the top of the pyramid towards vulnerable people,'" he said. "They never think, 'That could be me.' They just assume, 'That person is naturally inferior.'"

"... Let's bear in mind that America just had midterm elections where $4 billion was spent on campaigning — which is just telling you that something's good. But feeding the homeless? That's illegal."

The background: Brand has a habit of going off on tangents, but there's a harsh bit of truth here. The arrest of 90-year-old Arnold Abbott for violating new city regulations on when and where food could be distributed to the homeless is just the latest in a push by the Fort Lauderdale city commission to crack down on homelessness. Fort Lauderdale businesses were behind much of this, backing rules allowing cops to seize possessions stored in public and lock up people for going to the bathroom outdoors for up to 60 days. The Sun Sentinel reported in April:

The commission's actions were backed by business leaders who said they were looking for some controls on a situation that scares away customers and makes visitors uncomfortable — and residents feeling the community is being overrun by homeless people.

So it seems that Brand's tirade against businesses for their part in this is actually pretty spot on. And, the thing is, he's right.

"Cities' hope is that restricting sharing of food will somehow make [the] homeless disappear and go away," The National Coalition for the Homeless' Michael Stoops told The Salt. "But I can promise you that even if these ordinances are adopted, it's not going to get rid of homelessness."

As for that popular mentality Brand is talking about, it's measurable. A 2011 report commissioned by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority found that people have condescending attitudes toward the homeless and over-estimate how many homeless people have mental health or substance use problems. The authors concluded that if people think of "personal failings as the main cause of homelessness, it is unlikely that they will vote for increased public assistance or volunteer to help the homeless themselves."

Why you should care: Laws designed to crack down on high rates of homelessness are counterproductive because they don't address any of the root causes of homelessness, yet the National Coalition for the Homeless reports that such regulations are increasingly common across the country. In 2013 alone, 23 cities passed bans similar to Fort Lauderdale's.

While Brand sometimes makes it hard to agree with him, he has a point: Helping the very poor is an unfortunately low national priority. Total welfare spending under the TANF program was just 0.47% of the 2012 federal budget. The Center for Budgetary and Policy Priorities reports that "states now receive 30% less in federal TANF funding than when Congress enacted the welfare law in 1996."