#BlackLivesMatter Must Move Beyond Protests — Or Risk Losing the Fight for Racial Justice

Witness the rupture.

Once the worry of minorities and leftists, the ease with which a white man with a badge can end the life of a black person is finally on America's mind. The realization that police practices can be brutish and unfair to black men has become a matter of serious concern for many whites, bourgeois liberals and some conservatives — apparently even George W. Bush. Law enforcement is undergoing a crisis of legitimacy.

The window of opportunity for the racially equalized institutional changes is wider than it's been in decades. The recent non-indictments for police killings in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, have reignited awareness of the systemic nature of racial discrimination. Riot, protest and media pressure has made the White House anxious and piqued the interest of a generally useless Congress. Some modest reform is in the works.

But all of this is fragile. When there is a long enough pause in the rate at which black men are killed by the police, the cameras will point elsewhere. If there is any hope of reaping lasting change from this moment, it must take shape in the form of something more durable than rage.

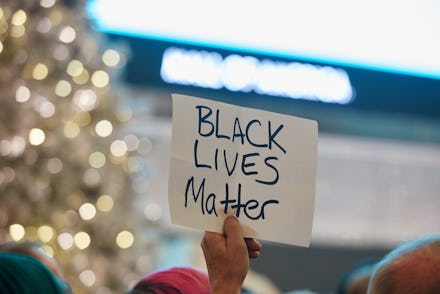

"Black Lives Matter" is the closest thing to a unifying banner for the demonstrations in response to the absence of justice in Ferguson and Staten Island. It's a slogan, a website and a Twitter hashtag, which first surfaced in 2012 in response to vigilante George Zimmerman's acquittal after he killed unarmed black teen Trayvon Martin. At this point, the phrase has become shorthand for the various streams of resistance to police brutality across the country.

The Black Lives Matter movement resembles Occupy Wall Street in 2011, which is cause for both celebration and concern: Both establish a polarizing antagonist — police, bankers — who serves as an entry point for structural critique (systemic racism and politico-economic inequality, respectively). Both have given birth to and mobilized highly decentralized, politically diverse and fairly spontaneous protest movements. Both operate in the register of contentious politics and feed off friction — or the threat of it — with the state. And just as Occupy mostly dissolved during its first winter, so too could Black Lives Matter.

So now the movement must evolve. Here are three ideas for those interested in carrying on with campaigns under the umbrella of Black Lives Matter:

Public protest is a tactic, not a strategy: Protesting is vital, but it's not a substitute for the organization, discipline and grit needed for long-term change. Groups small and large need to organize locally and coordinate nationally on specific programs with short- and long-term goals. Resources for political, economic, legal and cultural advocacy need to be pooled and employed strategically. Campaigns for reform — whether assigning special prosecutors for police homicide trials, disarming the police or closing the white-black wealth gap — must be focused. Local community efforts should be paired with efforts engaging the federal political process.

Past efforts with similar agendas provide useful case studies. One example worth considering is the rise of the Black Panther Party in response to police brutality in the late 1960s through the early '70s. Typically depicted as armed separatists, the Black Panthers were antiracist and committed to building interracial coalitions. Their most divisive position, advocacy of armed self-defense, was only one relatively short-lived element of their complex political program. Soon after they developed a nationwide following, they focused on community programs providing free services to neighborhoods; their most popular nationwide initiative was the Free Breakfast for Children Program. The Panthers' other communitarian programs — which included free clothing, medical care, transportation, housing cooperatives and much more — highlighted the shortcomings of the state and economy, while empowering ordinary citizens to conceptualize and participate in an alternative political economy.

Successful political movements have always focused on liberation.

The Black Panthers began as a response to the police, but quickly evolved into a broader vision of how people of color can find dignity and autonomy in a congenitally racist country; they knew that oppression by the police was inextricable from oppression in economic and political life. While their practice of armed resistance was ineffective in the long-term, and is certainly not something that should be embraced today, their holistic view of change merits study. Their 10-point program connected their concern with self-defense to a broader agenda of wholesale social change, and it intended to capture political and economic gains that the Civil Rights movement had failed to target or secure.

While it's tragic that today's grievances bear such a strong resemblance to those of the '60s, it bodes well that today's conversation has been similarly panoramic in its discussion of racial injustice and the actions that will be needed to address it.

Use civil disobedience to generate attention: During the Civil Rights era, activists gained legitimacy not just by expressing discontent publicly, but also by actively defying unjust laws. Protests and die-ins are valuable, but they do not have the same ability to captivate as the sacrificial spectacle of nonviolent refusal. A willingness to endure arrest is a powerful asset, and it's something that white allies can bring to the table in a big way. Recall Occupy's explosive growth in popularity and media attention when police overreacted to occupations with mass arrests and pepper spray. Today, peaceful resistance to the institutions that are behind today's crisis can take many forms, but it will need to go beyond permitted marches.

Words matter: Lastly, it's worth contemplating the limitations of the slogan "Black Lives Matter." It's a defensive plea that affirms its own unreality in the criminal justice system. While its vagueness allows it to cast a wide net as a brand, it's also unambitious; "Black Lives Matter" sounds like a cry for general validation rather than a non-negotiable demand for freedom from discrimination. "Hands up, don't shoot" is another popular slogan at protests these days, and it also suffers from defensive posturing.

Framing matters. As political scientist Corey Robin has explained, today's liberals' defensive language on everything from taxes to foreign policy often reinforces the conservative paradigm they take issue with, while successful political movements have always focused on liberation:

From Emerson and Douglass to Reagan and Goldwater, freedom has been the keyword of American politics. Every successful movement — abolition, feminism, civil rights, the New Deal — has claimed it. A freewheeling mix of elements — the willful assertion and reinvention of the self, the breaking of traditional bonds and constraints, the toppling of old orders and creation of new forms — freedom in the American vein combines what political theorists call negative liberty (the absence of external interference) and positive liberty (the ability to act). Where theorists dwell on these distinctions as incommensurable values, statesmen and activists unite them in a vision of emancipation that identifies freedom with the act of knocking down or hurtling past barriers.

There is no simple answer to this problem — one that afflicts the left as a whole — but the language of Black Power could provide a useful toolkit for Black Lives Matter.

As we enter 2015, let us resolve to stay the course in working toward more inclusive notions of freedom. The fire must keep burning, but it's also going to have to burn slowly.