The Sacred, Profane and 'Charlie Hebdo': Why We Must Protect Art’s Ability to Shock

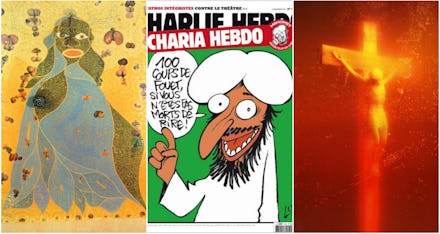

In 1999, artist Chris Ofili put on display in New York City a painting he made depicting the Virgin Mary as part of an exhibition called Sensation. The work, "The Holy Virgin Mary," is a riot of tropical color that plays toward none of the usual cliches of Western Christian imagery. Mary's skin is dark and her lips wide and red. Her robe is open to bare one breast, which is represented by a piece of dried elephant dung that Ofili had appropriated. Looking closer, it's apparent that the image itself is made up of collaged pornography.

Interpreting the piece without understanding Ofili's background as a Roman Catholic or failing to appreciate the work's visual beauty and its unorthodox celebration of such a revered Christian icon, it might seem Ofili was degrading the holy by mixing it with the lowbrow, forcing the sacred to intermingle with the profane.

That's certainly how some saw it. New York City's mayor at the time, Rudolph Giuliani, called it "sick" and sued the Brooklyn Museum to take it down. Under the First Amendment, however, the museum won, and the painting stayed on display.

More than a decade before the debut of Ofili's "Dung Mary," photographer Andres Serrano submerged a plastic statue of Jesus in what he described as a plastic tank full of his own urine. The piece, "Immersion (Piss Christ)," is a little nauseating but not aesthetically unpleasant: The color is a deep, luminescent yellow, and the figurine's pose remains beatific despite its context.

Yet when "Piss Christ" was exhibited in 1989, two U.S. senators called for its removal and expressed outrage that Serrano had received funding for his work to the tune of $20,000 from the government's National Endowment for the Arts. Serrano received death threats, and the piece has provoked controversy ever since. One version mounted in France was damaged irreparably by hammer-wielding protesters in 2011.

Yet unlike Stéphane Charbonnier, the editor-in-chief of Charlie Hebdo, Ofili and Serrano are still alive.

Ofili and Serrano escaped their artistic controversies with little more than bruised egos. The journalists, cartoonists and staffers killed at the French satirical magazine Wednesday were not as lucky. These creators died standing by their satirical art.

The events prove that even with the constant bombardment of images and narratives going viral, art retains its ability to shock us. In fact, it is art's purpose to provide such a shock. But no matter how controversial, this is a purpose no one should ever have to die to defend.

In 1913, Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring" inspired near-riots in its audience, shocked at the composer's avant-gardism. In the '80s, Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses drew violent protests in Pakistan. The millennia-old Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan proved so offensive to the Taliban that the sculptures were blown up in 2001.

These examples, alongside the Charlie Hebdo massacre, show that we still haven't answered a fundamental question: How can we accept art that crosses the boundary between the sacred and the profane?

Islam is an iconoclastic religion in a literal sense — it forbids depictions of the Prophet Muhammad. This ban may have been the cause of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's pulling of images of Muhammad from its Islamic collection galleries in 2010, according to the New York Post. The French magazine crossed this boundary pointedly and often for all organized religions, so far that the publication had more legal run-ins with Christian organizations than Muslim.

The creation of a caricature of Muhammad printed on a magazine's front page or an effigy of Jesus dunked in urine hung in a gallery are not inherently tasteful acts. As some have pointed out, the cartoons published by Charlie Hebdo might represent a virulent strand of anti-Islamic racism, with their simplistic caricatures of Muslims engaged in self-referentially absurd acts, like making out with, say, a French cartoonist. As Jacob Canfield writes in an exhaustive deconstruction of the magazine's work, "free speech does not mean freedom from criticism."

In this case, we must be able to evaluate the art while condemning what happened to its creators and upholding their ability to be controversial within the bounds of free speech. This can be a difficult process. Art, after all, is made to "undermine the sacred," Arthur Goldhammer wrote in Al-Jazeera America.

The need to accept controversy is as true for Charlie Hebdo's work as it is for the work of Serrano or Ofili, who managed to offend members of a different religion — Christianity — who would doubtless hold themselves far above the ideology of Islamic extremists. In either case, when art shocks, when it offends or profanes, the proper response is not lashing out in anger but asking yourself why it's offensive and what its supposed trespasses against the sacred mean.

How can we accept art that crosses the boundary between the sacred and the profane?

The ideas we hold sacred are often the most worth reconsidering. And if art cannot be allowed to create dialogue between cultures, what will? Little else throughout history has proven as effective at translating between nations and peoples.

"The whole point of Charlie's satire was to be tasteless and obscene, to respect no proprieties, to make its point by being untameable and incorrigible," writes Goldhammer. "In mourning the tragedy, let us not forget that Charlie Hebdo was shocking, obscene and offensive because the world is."

What we need now is for creators to keep provoking — and we need to support artists in making work and prompting cultural discussion, whether we like it or not. Fellow cartoonists have created the most poignant, striking responses to the Charlie Hebdo murders: The imagery of the cartoons they have created often feature pens as counterpoint to guns. In this conflict, the former is creative and the latter apocalyptically destructive. Regardless of personal politics, it's not hard to come down on the side of creation, of more speech rather than less.

A drawing by Lucille Clerc that went viral after the Instagram account of satirical artist Banksy posted it shows an image of a whole pencil labeled "yesterday," a broken pencil labeled "today" and the two halves of the pencil sharpened anew labeled "tomorrow." The cartoon shows that art, like satire and comedy, is indomitable: Wherever it is pushed out, it comes back twice as hard. We can expect the spirit of Charlie Hebdo to do the same.

We must have faith in our society's artists, whether it's Ofili or Serrano or another painter, cartoonist or writer, that they are illuminating truths worth seeing, despite the apparent shock value of their work. The true importance lies deeper than the surface, in the dialogue and progress art promotes through its provocations.

Finally, the best memorial is Charbonnier's own quote, an epitaph that serves as a lesson to never let anything silence us: "I prefer to die standing than living on my knees."