One Week After 'Charlie Hebdo,' Here's the Lesson No One Is Thinking About

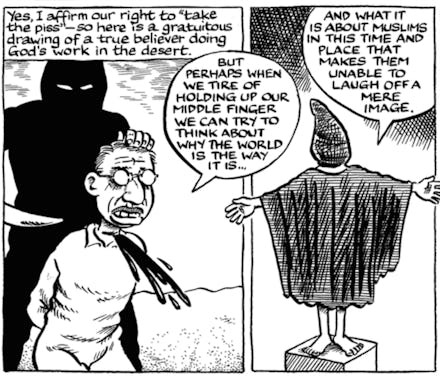

The conflict at the heart of Charlie Hebdo has nothing to do with Islam and everything to do with art and cross-cultural representation.

But you wouldn't know that judging by the response to last week's events in Paris, which brought global attention to the Islamophobia brewing both within France and abroad. There have been at least 54 documented anti-Muslim hate crimes committed throughout France since last week's horrifying attack, which killed a dozen people, including Charlie Hebdo journalists, cartoonists and two police officers.

This misguided retaliation holds the entire Muslim community accountable for the crimes of the extremist few. But it's nothing new: Artists have historically been vilified, imprisoned and even murdered for their art. But the Charlie Hebdo massacre is a symptom of a much larger problem having to do with cultural collisions. In an increasingly globalized world, artistic renderings of other cultures and ethnicities can no longer only be viewed through a Western lens. Technology has made us all neighbors, and artists are in a powerful position to embrace this by becoming more conscientious about living in a world where there are no longer borders to keep cultures segregated. And they can challenge their audiences to do the same.

A more closely connected world means new conflict about identity and representation. The Internet has broken down the boundaries that historically existed between cultures. At the click of a button, an image or thought is immediately shared to the world. It is the nature of something going viral. Within hours of the Paris shooting, for instance, over 166,000 tweet used the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie and over 3 million people used #CharlieHebdo just hours after the shooting.

As a result of the immediacy provided by the Internet, representation in media, cartoons and film no longer get a free pass. More than ever before, cultural stereotypes of minority identities are challenged and criticized for their sexism, racism and xenophobia.

Charlie Hebdo's brand of humor is far from unique. Remember The Interview, illegally downloaded at least 750,000 times within the first 20 hours of its online release?

Last month's backlash against the racism and homophobia of The Interview is yet another instance of this cultural conflict. In this case, the object of alleged "satire" was North Korea, and the country seemingly sought revenge by hacking into Sony's emails and leaking private documents (according to the FBI).

The problem is satire is subjective: A Western literary concept, satire's effectiveness hinges on the ability of viewers to understand it. But this doesn't always happen. Just look at the #CancelColbert hashtag campaign (a reaction to unpopular jokes about Asian-Americans) or the diatribes leveled against Lena Dunham's skewering of millennials on Girls.

If satire is prone to fail within its own culture, imagine how well it fares between cultures.

"What's funny and what's offensive aren't static concepts and are informed by all kinds of dynamics, both specific and broad and immediate and old," Gene Demby argues in his insightful piece about cultures colliding over at NPR. "There are no hard-and-fast rules — any that exist are specific to our contexts. What we need, as always, are better understandings of contexts that are not our own."

The takeaway: Whether it's Charlie Hebdo or James Franco, white men of the Western world have spent centuries assuming their world views are the right ones. Last week's attacks in Paris shattered this illusion, revealing that culture and values (both aesthetic and ethical) are relative. What we need to do is think more globally about how we represent one another in art and in discourse. Artists and satirists are in an ideal position to step in and depict cultures in a nuanced, sensitive and challenging way.

This is not a call to political correctness or limitations on artistic freedom. Calling for an ethical awareness is not the equivalent to censorship. But in an increasingly interconnected world, artists must go forward with knowledge of, and responsibility toward, the objects of their art.