The Handwritten Love Letter Is Dying — Here Are All the Wonderful Things We'll Lose

The evidence of my earliest forays into romance are in a manila envelope on the bottom of my old desk, squirreled away in a corner of the bedroom in the house I grew up in.

As a young man raised on '90s rom-coms like 10 Things I Hate About You and American Pie, thrust into navigating romance and courtship, I fully embraced the idea of writing love notes, if for slightly nerdier reasons: Ovid wrote them. So did the likes of Ludwig von Beethoven and Jane Austen. My literary impulse was affirmed by pop culture: Hell, the entire plot of Can't Hardly Wait revolves around Ethan Embry's kind-of-MacGuffin love letter to Jennifer Love Hewitt.

So I wrote love notes for my high school sweetheart — lots of them. I left them in her locker and in our school theater. I left them around the library. I snuck them into her purse and backpack so she'd see them after we'd parted ways for the evening. She lived less than two blocks away, and I'd often walk by when she wasn't home and leave them in her mailbox. This was pre-Facebook, and I wasn't really keen on the current digital tools: I didn't email or text much, and the closest I'd get to digital romance was hanging out on AIM late at night.

The week after we broke up in college, the envelope arrived, full of every letter or note I'd ever written her. My ex and I don't talk anymore, our lives moved in different paths in the decade since we met. But every holiday or unexpected excursion back home, after a few drinks, I find myself up at nights reading through these old strips of paper, these last remnants of a relationship long past.

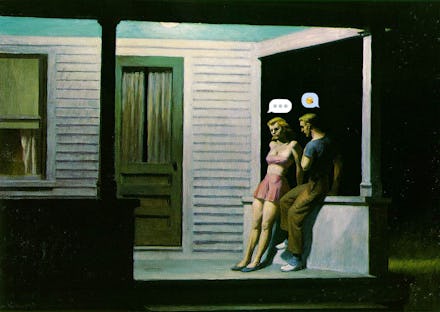

Soon, this ritual will turn into a remembrance of a medium past, too. Romantic writing is alive and well, made more democratic and commonplace by technology. But today's digital love notes don't actually capture what makes love letters so powerful in first place — the aesthetic and emotional value of the act of handwriting and the resultant physical artifact that lives on.

The love letter, the medium of Beethoven and Embry, is facing a slow and painful death, and it's taking one of humankind's most beautiful expressions of love with it.

The love letter has a long, rich history: Love letters have evolved to fulfill and express a myriad of human desires. Histories of love letters exist — of celebrity love letters, literary ones, ones written by kings and queens and presidents — but there's no one definitive history of the romantic missive. Laura Boyle of the Jane Austen Center suggests that the love letter's earliest manifestation may perhaps be the Bible's Song of Solomon: "Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth! For your love is better than wine; our anointing oils are fragrant; your name is oil poured out; therefore virgins love you. Draw me after you; let us run. The king has brought me into his chambers."

Love letters took on a less biblical tenor in the writings of Cicero and Pliny, who penned affectionate letters to their wives. But Boyle argues that the love letter as a literary form probably began in the early Renaissance, evolving further in the period of the Enlightenment.

Romantic writing is alive and well . . . but the love letter, the medium of Beethoven and Ethan Embry, is facing a slow and painful death.

"In the early 18th century, love letters became much more personal and pure," Boyle writes, a change from the chaste admirations and exaggerated language of the Middle Ages. "Missives from this period showed tenderness, charm and even humor. As the 18th century progressed and romantic ideals were cast aside, love letters too were changing. Intellectuals applied their ideas to the art, which they considered not to be trivial but rather essential to the search for self-knowledge and happiness."

The love letter evolved far beyond a literary vehicle for romance and affection, a foil for self-reflection and introspection. The great private love letters of Beethoven to his "Immortal Beloved" added a new dimension to his life and music; the messages from Napoleon Bonaparte to Joséphine seemed to transcend time, space and geopolitics.

Even Marlon Brando's 1966 pass at a flight attendant who caught his fancy tells us something of the mores of the time: "It's been a pleasant if brief encounter and I wish you well and I hope we shall have occasion to cross eyes again sometime." Well, shucks, Marlon — if only bros today were like you.

Technology should theoretically make love notes better: The explosion of digital communication in the past decade has made the world smaller and, in turn, our connections more ubiquitous and constant. No longer constrained to the arduous task of penmanship, our romantic overtures come pouring in through email, in bursts of GIF-powered nods and winks sliding into your DMs. We write one-size-fits-all missives on Tinder. An emoji is worth a thousand words, its meanings constantly in flux.

And this is, for the most part, a great thing. The majority of people see the Internet as a net positive in terms of developing and maintaining relationships. In a 2013 Pew Research Center survey, 59% of all Internet users agreed with the statement that "online dating is a good way to meet people," a 15-point increase from the 44% who agreed in 2005. Hell, 29% of Americans know someone who met their spouse or other long-term relationship online. A 2014 survey found 67% of Internet users say their online communication with family and friends has generally strengthened those relationships.

We write one-size-fits-all missives on Tinder. An emoji is worth a thousand words, its meanings constantly in flux.

"Computers, fax machines and modern transportation have not outdated the art of the love letter," muses Boyle. "Instead, they have fueled its interest and effect. Love letters can now be emailed, faxed and even sent overnight to lovers separated by oceans and continents. Clearly, the love letter has evolved through the ages, only to become more treasured and meaningful in the present day."

Except this isn't totally true. The handwritten love letter, the literary aphrodisiac of the last two centuries, is one of the most personal, powerful expressions of romance whose qualities cannot be truly replicated in the digital world.

Writing and typing are not the same act: While there isn't much data on how many people hand-write love notes today, a U.S. Postal Service survey did find that the average U.S. home only got a personal letter once every seven weeks in 2010, down from once every two weeks in 1987. A U.K survey from 2010 found that one in five British children had never received a handwritten letter, and a tenth had never written one.

And that's a real loss. The act of writing a physical letter imbues communication with a level of uniqueness, a sense of space and time lost in the conversion to the flat landscape of digital communication.

Writing by hand forces us to think methodically, thoughtfully and carefully, without the benefits of Control-Z or the shortcut of emojis. "To form, strengthen or repair a relationship we must give time and meaningful attention to the other person; that's what I do when I handwrite a note," writes Jim Ross in his beautiful tribute to the handwritten note in the Morning News.

"I think out the sentence, the spelling, the phrasing. I don't write as quickly as I type, so that slows me down right away. There's no backspace/delete if I don't properly express the thought the first time, and, of course, I want to get the message just right — that slows me down even more. The physical acts of grabbing the card, finding the postal address, preparing the envelope, and affixing the stamp all take time, as well.

Slowing down the process turns the focus to the recipient, Ross added, making handwriting a glorious contrast to the banalities and immediacy of, say, Gchat.

"If talking is one thing, and conversation another, then what is chat?" asked the editors of literary magazine n+1 in an essay considering Internet communication. "The medium creates the illusion of intimacy — of giving and receiving undivided attention — when in fact our attention is quite literally divided, apportioned among up to six small boxes at a time. The boxes contain staccato, telegraphic exchanges, with which we are partially and intermittently engaged," they noted. Gchat "offers us so many opportunities for conversation that conversation becomes impossible. We are distracted from chatting by chatting itself."

Handwriting forces us to think methodically, thoughtfully and carefully, without the benefits of Control-Z or the shortcut of emojis.

This isn't to say that all messages written online are emotionless or lacking in authenticity or intent, as You've Got Mail proved. And our regard for people, as Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves' seminal 1996 The Media Equation reminds us, is no less diminished because our communication takes place through screens.

And to be fair, when it comes to authenticity, all social interaction is a farce at some level. Love letters are just as deliberate a construction as the strategic Gchats and emails we deploy in our daily lives. Internet flirtation is not more or less authentic than a love letter — "authenticity" is a dead term anyway, and the New York Times Sunday Review killed it — but it's less structured, more organic. And that's not always a bad thing.

But the beauty of love letters, as Ross put it, lies in the passionate, deliberate desire to "get the message just right." Writing by hand slows us down and turns the act of writing a love letter into an act of composition, of reflection, of introspection, with the recipient front of mind.

The written artifact has more staying power than an email ever can: As every first-year media studies student knows, the medium and message are inextricably entwined. Writing a love letter is an act of literary craftsmanship. Part of the enduring power of handwritten notes from the likes of Beethoven and Brando is that they are true artifacts of romance, embodying the best and most intimate parts of the writers physically and emotionally.

From the smell and texture of the paper to the quirks of handwriting, the physicality of a love letter carries more context, meaning and memory than a note dashed off on a smartphone in the back of a cab. (A former student of my grandfather's, a longtime history professor, once claimed he could tell how long Professor Keller had spent reading a paper based on how deeply it reeked of cheap cigars.) After all, it's proven that sensory experiences, especially olfactory ones, can be powerful triggers for memory. In cyberspace, love has no scent.

They are true artifacts of romance, embodying the best and most intimate parts of the writers physically and emotionally.

The physical and aesthetic trappings that make the love letter great are being edged out by an advancing army of messaging apps and devices. The deliberateness of guiding a pen across paper, the uniqueness of loopy handwriting on a tortured sheet of paper, the scent and smell and memory of opening and reading and rereading — all of these things exist elsewhere, in another time reserved for other people who didn't have email.

There's a level of intimacy, of authenticity and of romance in actual letters more powerful than any instant communication can afford now. Years later, these artifacts tell stories about relationships that few historians will ever be able to know or understand unless they were reading over the writers' shoulders.

In recalling my first love, I could look at photos from our trip to Cape Cod and of us playing beer pong in suburban basements — all nostalgic, but they fail to capture the emotions felt at the time. Or I could click through final emails from girlfriends past or peruse old chat histories, but all fall short in giving me a sense of who and where I was when I wrote those loving words.

Leafing through my returned letters in my childhood bedroom, however, I can remember exactly when and where I wrote them — beside a campfire at the summer camp I worked during my teens, in a basement clogged with a haze of pot smoke and whiskey, on the shores of Walden Pond (yes, I'm a New England kid). Those memories are baked into every drop of ink on every page.

Most importantly, a decade later, that manila envelope is a much-needed reminder that one of the most powerful tools of modern romance lives on. All you need is a pen and paper.