Here's What Our Obsession With Steve Jobs Really Says About Us

If you're not sold by the tech community's beatification of Steve Jobs, you should watch Alex Gibney's new documentary. Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine, currently in theaters, might not be full of industry-shattering revelations about the late Apple CEO — Gibney had limited access to Jobs' family, close friends and colleagues, and much of the information within can be found in Walter Isaacson's more evenhanded biography — but it does lift the godlike Jobs off his pedestal above Silicon Valley and show a little grime.

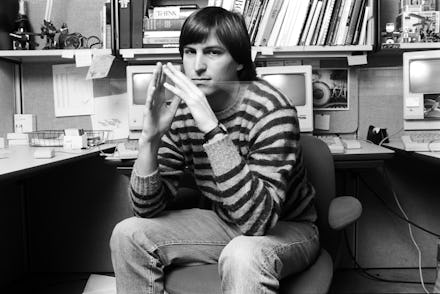

To much of the world, Jobs was a humble messenger who cast down from heaven lightning bolts that materialized in the form of friendly gadgets. We glimpsed Jobs twice a year in world-changing, earth-shaking product launches, much like the 2015 keynote address we're about to witness. He unveiled the future, and then we lined up at Apple Stores to experience it.

Apple's meteoric rise came at great cost to those who were close to Jobs.

When Jobs died in 2011, people held vigils and cried, as Gibney notes. They filmed their tears using their iPhones and iPads and uploaded those videos to YouTube. In Budapest, fans left flowers at a statue of Jobs holding the iPhone. Maybe the Cult of Mac never really understood the man they worshipped, or maybe they didn't care. What Gibney makes clear is that Jobs' genius and his substantial personal failings were two sides of the same coin.

Jobs was a legendary asshole, personally and professionally, and he was first to admit it. His technology may have connected billions of people, but connection itself was not the man's strong suit. Still, don't let that lead you to believe Jobs was a paradox, a man of contradictions: His incapacity for empathy was an intrinsic part of his success. Apple's meteoric rise came at great cost to those who were close to Jobs.

In many ways, Jobs embodied American exceptionalism. He was a man who believed rules didn't apply to him, and he pushed others out of the way in the name of greatness.

He parked his Mercedes in handicapped spots, sometimes filling two spaces at a time. Unable to process fatherhood at age 23, he invented an alternate reality in which his daughter wasn't his. His single-minded focus on building the Macintosh left little room for a personal life, and so his relationships suffered. He arbitrarily denied employees stock options, didn't waste time with charity and refused to acknowledge the devastating environmental impact of his Chinese factories.

Jobs' "reality distortion field," as his colleagues called it, likely also killed him. Facing a cancer diagnosis, Jobs refused surgery for nine months and tried to will away his tumor with a vegan diet, acupuncture and visits to a psychic.

For 30 years, that ability to seemingly bend reality was used to push his engineers to meet impossible deadlines and appease unrealistic and impractical design whims. As a result, of course, his inventions directed the personal computing industry. Apple was light-years ahead of its time.

The maker and the merchant: Many Apple fanatics today might not have heard of Steve Wozniak, employee No. 1 at Apple. Woz, as he was called, was the brilliant programmer who created the Apple I computer, which Jobs figured out how to effectively package, market and sell.

Early on in their collaboration, even before Apple, Jobs worked for the video game company Atari. He had an assignment from Atari to build a circuit board for the game Breakout, which he farmed out to Wozniak. He made Woz complete the assignment in four days, agreed to split the paycheck, then collected a sizable bonus for Wozniak's efficient work and allegedly hid it from his friend.

In their relationship, Woz was always the maker, while Jobs was the merchant. Woz, the maker, may have achieved cult-hero status in the tech community, but Jobs, the merchant, is a divine being, beloved by millions worldwide. It says a lot about what we value in an entrepreneur.

Greatness, at any cost: With every Mac we bought, we made Apple the most valuable company on the planet and cast its CEO, with all his tactics for greatness, as an exemplar of American innovation. Our blind devotion to Jobs contributes to the Randian myth that true greatness justifies a disregard for law and humanity — a common and problematic attitude in Silicon Valley.

Somehow, Jobs was able to turn this Randian philosophy on its head. He created the idea that his products represented the ideals of 1960s American counterculture. From the classic "1984" and "I'm a Mac" ads to the "Times They Are A-Changin'" recital to Jobs giving IBM the finger, every new Apple release was, in its own way, sticking it to the man.

First, the "man" was IBM, Dell and Microsoft. Buying Apple products felt rebellious and cool. But then the scrappy computing underdog Apple became the man, and Jobs had to undergo some impressive mental gymnastics to rationalize his behavior while on top of the heap.

For example, when the tech blog Gizmodo obtained and wrote about a lost iPhone 4 prototype in 2010, Jobs had a little-known police force break into editor Jason Chen's house and seize his property. Responding to the incident, Jobs told journalist Kara Swisher he was simply upholding the "values" of Apple Computer.

At a screening of The Man in the Machine in New York City Aug. 27, Gibney, who previously directed documentaries on Scientology, WikiLeaks and Enron, was asked what he'd ask Jobs if he'd gotten a chance to interview him before his death. "If I had the opportunity to ask Steve Jobs one question," he answered, "it would've been ... 'What are your values? Explain your values.'"

What our obsession with Jobs says about us: It's natural for people to admire a well-designed product, especially a powerful tool that empowered humans all over the world. But it's the Jobs myth that's problematic: The ambitious tech leaders of tomorrow will look to Jobs and admire how he embodied capitalist principles to an extreme — his work was so important, his calling so much higher, that he was impervious to the social mores to which the rest of us humans adhere.

Ultimately, Gibney's film asks us quite literally to look at our reflection in our iPhones and realize we're complicit in this attitude.

Our obsession with Jobs has continued unabated since his death, even as the final products he developed — the iPad, the iPod, the iMac, Apple Music — have been eclipsed by bigger, faster, flashier versions. The bestselling biography and two biopics — the latest, an Aaron Sorkin-penned drama à la The Social Network, premieres next month — have cemented Jobs' legacy as the great technological visionary of our time.

To find out how he got there, look out for this peek behind the curtain. Or just open your iPhone's selfie camera.