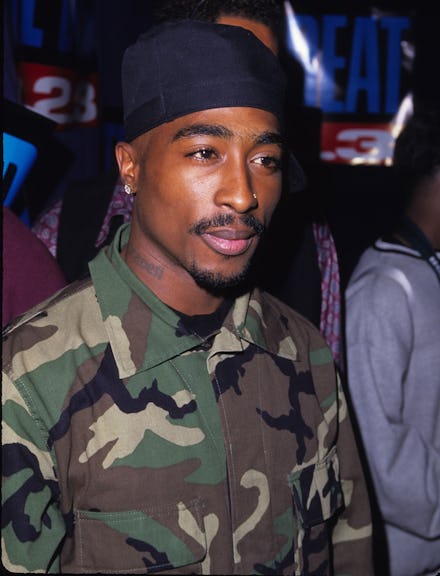

Oakland Elementary School Uses Tupac’s Poetry to Help Children Deal With PTSD

In the weeks leading up to the 19th anniversary of her son's death, Afeni Shakur found herself in an East Oakland, California, classroom trying to answer the question that's dogged hip-hop for the better part of two decades: Who killed Tupac?

The elder Shakur was dressed in a white linen blouse that contrasted beautifully with her smooth dark skin. Her warm eyes set behind her slightly oversized glasses. Maybe she's used to that question. Maybe she's not. But on this day, the person asking who'd killed her son wasn't a journalist or a rival. It was a small boy, no older than 9, who just wanted to know.

"It doesn't matter who killed my son," she said. "It matters why."

That boy and his classmates at Roses in Concrete Community School are part of an ambitious, community-based experiment that supporters hope is packed with answers about that "why" — why so many young people of color are caught in a vicious cycle of violence, and when they do survive, how they manage it. Shakur, with her daughter, Sekyiwa Shakur, were special attendees when the school last week welcomed the inaugural class of 196 students in kindergarten through fourth grade.

The school employs a full-time community organizer and begins each day with 15 minutes of meditation. The school draws its name and its mission from the poem, "The Rose That Grew From Concrete" written by a teenage Tupac. The piece was eventually adapted into a best-selling book of poetry published in 1999 after the rapper's death. "You wouldn't ask why the rose that grew from concrete has damaged petals," Tupac wrote. "On the contrary, we would celebrate its tenacity."

Just as Afeni Shakur said and her son wrote, the Roses faculty knows it's important to nurture and celebrate that tenacity. Vidrale Franklin, the school's principal, put it to Mic this way: "For a lot of families, we're their last hope. They've bounced from school to school because their kids weren't being successful."

Oakland is routinely ranked among the top five deadliest cities in the United States; many homicides occur in the stretch between the city's Lake Merritt and neighboring San Leandro that make up East Oakland.

Jeff Duncan-Andrade, a longtime educator and cofounder of Roses, gave a TEDx talk in 2011 during which he showed the Oakland Tribune's homicide map across 13 years, or the amount of time a student usually spends in the city's public schools. "You tell me where a young person can live in my community where they don't personally witness homicide," he told the audience.

What Oakland's children see: What Oakland experiences on a local level is part of what's only recently been identified as part of a long-simmering national epidemic: the impact of post-traumatic stress disorder in U.S. communities that are routinely under siege. Historically associated with combat veterans, PTSD is a clinical mental disorder sparked by exposure to a traumatic event and characterized by intense flashbacks, withdrawal, thoughts of depression and sometimes suicide. Nearly 8% of people in the United States will experience it at some point in their lifetimes, and anywhere from 11% to 20% of recent combat veterans have been diagnosed with the disorder, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

But black America has been suffering from a PTSD crisis that's been largely ignored until recently. When researchers in Chicago started screening patients for PTSD in 2011, they found that 43% of patients — and more than half of gunshot victims — showed some form of PTSD, according to ProPublica. Urban youth are twice as likely as soldiers returning from Iraq to have PTSD, according to a 2007 study by Stanford University researchers.

This problem is so prevalent it's earned its own name: CPTSD, or complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Instead of experiencing a traumatic event and then leaving it, as soldiers typically do, people who experience CPTSD are constantly exposed to their trauma over an extended period of time. The diagnosis "captures the complexity of young people living in urban poverty who return to the violence," Duncan-Andrade said in the 2011 TED talk.

How this pain builds: That trauma isn't just bad for students, it can be deadly. In 1997, the year after Tupac's death, a landmark study asked more than 17,000 adults about their history with adverse childhood experiences, ranging from physical and sexual abuse to living with a caretaker who suffered from a mental illness or was frequently imprisoned. The results were sobering: Compared with children who suffered no adverse childhood experiences, those who experienced four or more had a 220% increase in heart disease, a 160% increase in diabetes and were 1,220% more likely to attempt suicide. The stress associated with poverty didn't just inflict emotional pain on children. If left unchecked, it would eventually kill them.

But before it does, it will severely impact the way they learn. "They respond to the world as a place of constant danger," researchers at the Kirwan Institute wrote last year. "With their brains overloaded on stress hormones and unable to function appropriately, they can't focus on learning." That stress literally impacts their brain's development. Eighty-five percent of the core areas of the brain develop by the time a child reaches age 3, but for those who experience severe trauma or neglect, the part of the brain that's responsible for memory of emotional control will develop much more slowly.

For Zeyda Garcia, Roses in Concrete's counselor, the challenge of educating children with acute trauma is steep, but not insurmountable. "We're looking at our scholars as holistic human beings who are carrying everything in their lives into the classroom with them," she told Mic. "It helps having a staff of people who are on the same page and work from their heart and have the same desire."

Roses' educators are no strangers to Tupac's poetry in the classroom. Duncan-Andrade told Emily Wilson of AlterNet, "'Pac's work is about seeing the full humanity of someone who endures suffering and trauma on a regular basis, and I think that's what the most successful adults working in our communities do. They acknowledge the hurt and the unearned suffering while at the same time acknowledging the tenacity and the will to reach the sun."

In 2009, Duncan-Andrade laid out his theory on how educators can help grow roses from concrete in the Harvard Educational Review. "The ability to control, in a material way, the litany of social stressors that result from growing up in concrete is nearly impossible for urban youth," he wrote. Effective teachers were those who helped locate cracks in that concrete — food for the hungry, for instance — where children could flourish.

Only three weeks into the school year, it's too early to tell how effective Roses will be in its mission. But the staff seems committed to the long haul. Reena Valvani taught bilingual education to kindergarten and first-graders in neighboring San Leandro for 13 years before joining Roses this fall. She was so inspired by its mission she also enrolled her second-grade son, Narayan.

"I think we all anticipated coming into a very heavy workload and we've all been deeply humbled by how heavy that workload is," she said of the staff, which works up to 90 hours a week and on weekends. Still, she says, "it's incredible."