Remember Your Old Graphing Calculator? It Still Costs a Fortune — Here's Why

This year, high school juniors and seniors will buy a $100 calculator that's older than they are.

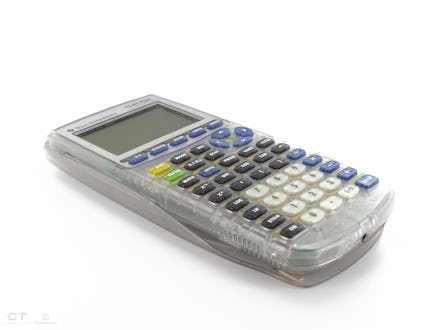

You remember the TI-83: the brick-sized graphing machine you likely covered in stickers and used to send messages, spell out obscenities, play games and maybe do some math, if you were paying close enough attention. Some students today will be the second generation to use it.

The TI-83 was released in 1996, when mobile phones had antennas and PCs were mostly used for word processing. In 1996, Google was born. It was also the year of the Palm Pilot and Hotmail. Microsoft Office '97 debuted on a floppy disk. You could install the Internet on your computer with a CD from AOL.

In fact, the TI-83 existed for half a decade before the iPod, which became smaller and more powerful for generations before it, too, became obsolete. The iPod made way for the smartphone, a computational powerhouse — the size of, well, a calculator — that is quickly taking over the world.

Technology has not yet killed the reliable old TI-83. Nearly 20 years later, students are still forced to use a prohibitively expensive piece of outdated technology. It's not because better tools aren't available; they exist, and some of them are even free. It's because Texas Instruments, the company that creates them, has a staggering monopoly in the field of high school mathematics. The American education system is addicted to Texas Instruments.

It's the Internet age. Why does anyone still use a clunky, expensive graphing calculator?

The primary driver of Texas Instruments' incumbency: TI-series calculators have been so prominent for so long, they've worked their way into the bloodstream of mathematics instruction in the U.S.

Pearson textbooks feature illustrations of TI-series calculators alongside chapters so students can use their TI calculator in conjunction with the lesson plan. The calculators also have a significant learning curve, and moving students over to new technology is a risky proposition when success in the classroom is so tied to the technology being used.

TI calculators have been a constant, essential staple in the slow-moving public education sector. Students and teachers are so used to generations of students learning the familiar button combos and menu options that TI provides a computer program that perfectly resembles the button layout of the TI-83.

However, even if teachers wanted to be bold and bring in better technology, they would end up right back at square one because of that infamous force in American education: standardized testing.

College Board and other companies that administer the country's standardized tests have approved lists of calculators. TI-series devices are ubiquitous — mobile apps are nowhere to be found.

"I'm actually at the point now where when I do parent conferences, I tell the parents it's in their students' best interest to buy one, because the device will become necessary," Bob Lochel, a math teacher in Hatboro, Pennsylvania, told Mic. "But you feel dirty, because you're telling parents they need to buy a device, and I know I can teach without it."

Mic's sources say that Texas Instruments provides services like technology and emulators for free to companies like College Board (Texas Instruments did not return repeated requests for comment). Texas Instruments also keeps a standing militia, an organization called Teachers Teaching for Technology (T3) — the church of Texas Instruments. T3 has programs to educate teachers on how to best use Texas Instruments calculators, a hotline called 1-800-TI-CARES and a yearly conference.

A few math teachers told Mic that while the T3 program offers support and communications, it's lacking in organization and community, and in turn the members become evangelists for T3. At conferences for organizations like the National Council for Teachers of Mathematics, Texas Instruments constructs massive pavilions.

The way Texas Instruments works with testing companies, standards boards, teachers and textbook publishers is reinforcing the achievement gap between upper-middle-class students and everyone else.

It's a profitable technological incumbency that is nearly monopolistic. In the 2013-2014 school year, Texas Instruments sold 93% of all graphing calculators in the U.S. The Washington Post estimates that TI is manufacturing the calculators for $15 to $20 and achieving a more than 50% profit margin, making calculators one of the company's most profitable items.

There's no reason they should cost so much, and it's shutting out students who can't afford them. Just this past week, Amazon started selling Internet-capable Kindle tablets for $50 each. But a new TI-84 still runs a retail price of $100, and classrooms that use TI-Nspires (the newest addition to the TI line) are shelling out $140 a pop — about the price of a brand new Chromebook. All for a calculator that is older than the .MP3 file extension.

Worse, the calculator is starting to show its age. "Perpendicular lines don't look perpendicular because the window is a rectangle," one Texas-based math teacher told Mic.

Even buying a TI-series graphing calculator for a reseller at a major discount can't compete with the Casio-made alternatives, which sell for $50.

Lochel told Mic, "I tell kids when they buy graphing calculators, 'You know what the difference between TI and Casio is? Marketing.'"

"I tell kids when they buy graphing calculators, 'You know what the difference between TI and Casio is? Marketing.'"

This cost can be prohibitive for students who can't afford to shell out over $100 for a graphing calculator, and anyone who's ever had one stolen knows they're a hot commodity. The way Texas Instruments works with testing companies, standards boards, complicit teachers and textbook publishers is reinforcing the achievement gap between upper-middle-class students and everyone else.

Some schools that have the budget to provide graphing calculators in every classroom, and can even sign them out for students when they have to take a standardized test. But that's not the case for schools without the economic means. Vernon, a teacher in the South Bronx, told Mic that he's not sure if his school could afford a large volume of calculators for their classroom, which is why his class uses free apps that do the jobs just fine.

There's an app for that — if it can manage to unseat the reigning king of calculation. It's called Desmos, an online calculator and mobile app that has all of the graphing functions of a graphing calculator. Desmos' business model is the opposite of Texas Instruments'. Desmos CEO Eli Luberoff charges companies like Pearson and College Board for integrating the app with the website, while the app is totally free for students and teachers.

The app is elegant, responsive and instantly graphs data as it's plugged in. It performs all of the same functions a TI graphing calculator does, even if there are some things that the TI-Nspire has added in order to compete.

"With the NSpire, I have everything in one piece of software, so I'm not going between seven different windows," Jennifer Wilson, a math teacher in Mississippi who is (admittedly) a member of T3, told Mic. "I'm not switching between seven different pieces of software to send a poll, or graphing, or geometry, or data collection."

Desmos is also bare, intuitive and much easier to learn. However, out of a small survey of students who have used both Desmos alongside a Texas Instruments calculator, students overwhelmingly chose the TI. Cathy Yenca, the Texas teacher who gave the survey, chalks it up to the fact that calculators are programmable.

"You can dump a list of numbers to find the mean, median, mode, list, every statistic into the sun," Yenca told Mic. "It's more worth it for kids."

"The learning curve is higher, but the buttons... students love pushing 'em."

Plus, she says, her kids love the fact that the calculators are clunky and tactile, an opinion anyone who misses the tactile, QWERTY keyboards of earlier smartphones shares.

"The learning curve is higher, but the buttons... they love pushing 'em," Yenca said.

To anyone who thinks that letting kids use their phones as calculators will open kids up to the distractions of simply popping onto Snapchat or Instagram during class, every teacher we spoke to said this was a non-issue.

"When I was in seventh and eighth grade, we passed notes across the floor and in class," Lochel told Mic. "Students have these tools anyway. It's our responsibility to teach them in a professional way and use the tools responsibly."

What Lochel said about passing notes — that students would just be distracted by something else if it weren't for their phones — was echoed by most teachers we spoke to. Vernon says those same kids who might be cruising Kik during math classes might otherwise be running around punching random kids as an outlet instead.

"We can trust students a lot more than we think," Vernon told Mic. "Current high schoolers have grown up with mobile technology, so they seem to treat it more responsibly. When technology becomes disruptive, I don't blame the device, I blame the student."

The No. 1 barrier for Desmos to unseating Texas Instruments is tradition. Teachers, standards boards and testing companies are conservative, which Luberoff, who learned to program on a TI-83 as a kid, admits is a useful approach. It's also keeping the American classroom out of the 21st century. "To be blunt," Luberoff said, "it's not going to be that way for much longer."

Things are changing. Last year, the Eanes school district in Texas was the first to approve a pilot program where students were allowed to use Desmos-installed iPads on the Texas state assessment STAAR, using the Casper Suite of focus-management tools to shut the iPads out from any other app during the test-taking process.

Luberoff says that Ontario and Quebec are next up for pilot programs, and that he's in conversations with more potential partners about integrating Desmos with the traditional education gatekeepers. If you Google "graphing calculator," Desmos' online tool is your first result.

And recently, when the eighth-grade math teachers in the Eanes district had a curriculum change that meant they'd be exposed to graphing calculators, Yenca said that every single teacher defaulted to using an app on a tablet instead of a graphing calculator.

"A couple of years ago, I would have looked at the idea that an app would replace these calculators and thought it was crazy," Luberoff told Mic. "But a couple of years from now we'll look back and say that this was quite an era."