Silicon Valley Is Lying to You About Economic Inequality

Multimillionaire Silicon Valley CEOs have found themselves on the good end of a miserable deal. As inequality in our economy and society widens even further, some of our nation's wealthiest people have stepped up to try to confront it head-on. Others have thrown up their hands and said, "It's not my fault!"

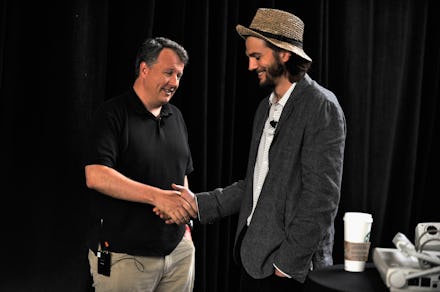

Silicon Valley luminary Paul Graham is a prolific and influential computer programmer who co-founded Y Combinator, a seed capital firm and startup accelerator. Graham spends much of his time advising ambitious young founders in the investment-addled tech business, helping to turn explosive amounts of money into profitable businesses.

Over the past week, Graham wrote a few essays addressing income inequality and Silicon Valley's role in exacerbating it. "I've become an expert on how to increase economic inequality, and I've spent the past decade working hard to do it," he explains in a screed that earned him the ire of tech critics and economists this week.

... when I hear people saying that economic inequality is bad and should be decreased, I feel rather like a wild animal overhearing a conversation between hunters. But the thing that strikes me most about the conversations I overhear is how confused they are. They don't even seem clear whether they want to kill me or not.

He argues that yes, economic inequality is real, but it's not bad "per se" — and even if it were, rich people in tech aren't the bad kind of rich people.

These tech billionaires aren't like other billionaires, Graham says — they have nothing in common with the gilded robber barons who attacked unions, built industrial leviathans that choked out the competition and bought politicians. The billionaires of Silicon Valley are better, and we can't hold them accountable for inequality.

He's wrong.

No, the tech industry does not "create wealth."

At the heart of Graham's argument is the idea that the rich of Silicon Valley haven't taken money from anyone else — that the economy isn't like a pie chart where you get rich by taking more of someone else's slice:

In the real world you can create wealth as well as taking it from others. A woodworker creates wealth. He makes a chair, and you willingly give him money in return for it. A high-frequency trader does not. He makes a dollar only when someone on the other end of a trade loses a dollar.

In other words: The tech industry generates new wealth. Graham says that "the rich aren't all getting richer simply from some sinister new system for transferring wealth to them from everyone else," even if hotels, record labels, the taxi industry and print ad salespeople would certainly use those terms to describe Airbnb, Spotify, Uber and the entire digital media landscape.

The marquee tech companies of the past decade have created digital empires where none existed before, true. But the claim that their wealth is entirely original doesn't hold up under close examination.

Research by economist John Fernald of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco shows that relative to the time when the internet was fresh and new, technology's recent contribution to the growth of the economy has slowed significantly.

"Many transformative IT-related innovations showed up in the productivity statistics in the second half of the 1990s and early 2000s," Fernald wrote with researcher Bing Wang in an online letter. "Over the past decade, however, productivity gains have been more incremental."

Of monopolies and men

Let's start with two particular qualities that corporations have used in history to advance inequality: using the power of monopoly to squeeze others out of a market, and hurting the ability of workers to secure their own rights.

Amazon shows us how tech companies can exploit power in a vertical supply chain to aggressively undercut any other competitor. The more business, distribution and consumer spending Amazon gathers under its umbrella, the more leverage it has to force entire industries to evolve on Amazon's terms. The publishing business bitterly fought that coup for years.

Uber shows us how tech companies can create labor markets that undermine established, regulated systems of employment. By setting up a business model where a driver is considered a "contractor" instead of an employee, Uber can avoid providing the kinds of labor amenities that traditionally allow for workers to share in corporate gains. Meanwhile, Uber claims to be creating a system full of new opportunities of transportation for the poor, though driver data proves that this is all PR.

Graham himself has expressed his own anti-labor sentiments. "Any industry that still has unions has potential energy that could be released by startups," he tweeted in November 2015.

In other words, unions set up guidelines and boundaries that prevent experimentation and innovation. Historically, that "energy" has been released by anti-union laws that erode the collective bargaining rights of workers. Or, throughout the history of the American labor movement for fair treatment of workers in the mining industry, factory workers and railroad workers, it's been "released" through killings, arrests, union busting and brutal beatings.

But tech companies don't have to break down unions. With an app, you can start a business entirely outside of existing legal frameworks and compete using your own set of rules.

"If you want to actually deal with poverty, you have to talk about how the whole economy works, including why some people are rich and some are not. They're two sides of the same coin."

For Uber, untapped resources like the extra working hours of the economically vulnerable are "released" through an extra-legal taxi system that either criminally evades regulation or, failing that, buys political players outright. Airbnb "releases" untapped cash when you break your leasing agreement to rent your extra rooms, and has mobilized millions of dollars to lobby against regulation (when Airbnb was taxed fairly, it covered San Francisco with passive-aggressive advertising).

Graham argues that, unlike oil barons and railroad tycoons, tech companies have no interest in exerting influence on publicly elected officials using their money. We know better than that.

Is there a better solution?

Graham ended his initial essay with a diversion: Instead of heaping blame on the rich, we should be focused on poverty itself — its effects, its root causes and how to treat it. As he put it: "When the city is turning off your water because you can't pay the bill, it doesn't make any difference what Larry Page's net worth is compared to yours." It's a fair assessment, if those two people — the one with the water turned off and the co-founder of Google — were totally unrelated, in separate economies where the flow of capital is governed by separate laws.

That's not the case. Marshall Steinbaum, an economist with the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, told Mic that portraying poverty as some sort of festering wound that needs a complicated, interdisciplinary intervention is bleary mythologizing.

"Poverty is not that complicated," Steinbaum told Mic. "Poverty is people not having enough money. If you want to actually deal with poverty, you have to talk about how the whole economy works, including why some people are rich and some are not. They're two sides of the same coin."

We need to worry about predistribution — how money gets into the hands of both the rich and the poor in the first place.

The most commonly proposed solution to the imbalance in wealth is redistributing that wealth through public programs or some sort of progressive taxation. After all, a country rife with plutocrats has potential energy that could be released by progressive taxation.

But Graham is right to say that simply redistributing the vast sums of wealth that are pooling into fewer and fewer hands doesn't solve the problem of income inequality at its roots.

Robert Reich, labor secretary under President Bill Clinton and public policy figurehead, told Mic in October that to address inequality and "save capitalism," we need to worry about predistribution — how money gets into the hands of both the rich and the poor in the first place — instead of treating symptoms after they've occurred.

"The only way we can begin to tackle all of these upward predistributions and create a market that works for all of us, rather than a few, is to change our politics and create — as we have had in various times in our history — centers of countervailing power, to balance our economy and democracy," Reich told Mic.