Hillary Clinton Just Announced an Unprecedented Plan For Environmental Justice

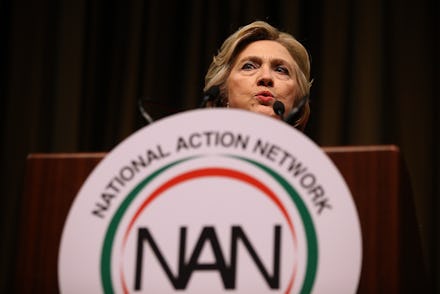

NEW YORK — Speaking before a crowd of veteran civil rights activists in Manhattan on Wednesday, Hillary Clinton announced her plan to make sure that a crisis like the one in Flint never happens again.

"Flint is not alone. There are a lot of Flints across this country," the Democratic presidential frontrunner said, in reference to the Michigan city that was discovered last year to have a water supply contaminated with extraordinary levels of lead.

Read more: Why Bill Clinton Just Tripped Up Hillary in the Worst Way Possible

Lamenting the lack of attention that's been given to environmental justice during this campaign cycle, Clinton said that some serious policy objectives in that realm were long overdue.

"I want to set an ambitious national goal to eliminate lead as a major public threat within five years," Clinton declared. "I say if we put our minds to it, we can get it done, let's set that goal and then let's get everybody moving toward achieving it!"

Clinton's remarks on her vision of environmental justice were something new for those who have been tuning in to her campaign, and she delivered it with passion. But the crowd, which had shown itself capable of some raucous energy during an earlier panel on the same stage, responded with only modest applause. Why would a crowd who cares deeply about issues like the horrors of Flint seem somewhat unmoved by Clinton's unassailably progressive commitment? The biggest clue lies in how she was introduced to the stage.

Location, location, location: Clinton was speaking at the annual convention of the National Action Network, a civil rights organization founded by Rev. Al Sharpton, one of the nation's most prominent living civil rights activists, in 1991. Initially, the network had local and regional impact, but its reach eventually grew national, and its annual convention is now one of the largest civil rights-focused gatherings in the country.

As the organization has aged and expanded, it has also evolved ideologically. NAN, whose banner slogan is "no justice, no peace" was once focused on getting people on the streets, rallying and marching, but increasingly it's shifted more toward policy and electoral politics. The annual convention has been dubbed "the Sharpton primary," and in 2007, it featured all of the major Democratic presidential candidates who ran in the 2008 cycle.

Sharpton introduced Clinton to the stage on Wednesday with a tone of respect and recognition of their friendship. He offered a funny anecdote about the time she'd once asked him how she could help him while he served time in jail for engaging in civil disobedience, and how he in turn asked her for a key. And he spoke with admiration about her confidence as an advocate and a lawmaker. But he also went out of his way to mention that they've had disagreements in the past, explicitly mentioning the 1994 crime bill as a point of tension.

That tough-on-crime bill, which has recently experienced a fresh wave of retrospective scrutiny in light of Bill Clinton's flustered defense of it last week, was likely top of mind for many people in the crowd. Through a crude demographic lens, the crowd sitting before Clinton would appear exceptionally Clinton-friendly — older, almost entirely black, close observers of Democratic politics. But it was also a group particularly well-versed in the way the tough-on-crime ethos that prevailed in the 1990s has inflicted extraordinary damage on communities of color. They're also particularly likely to be resentful of some of Clinton's past rhetoric on black communities, such as her reference to certain kinds of young black criminals as "super predators" in 1996.

Clinton hit all the right notes on how her contemporary policy platform prioritizes the interests of people of color. She spoke about the need to tackle "systemic racism" and her plan to invest in a "breaking every barrier agenda" that would account for the way racial discrimination shapes outcomes for people in countless spheres of American life, from the courts to housing to the workplace. She offered numbers and details on how she would do it, and she sounded resolute. But, as a couple members of the audience told us after the speech, the specter of the 1994 crime bill seemed to hang around even after Sharpton had left the stage, lingering throughout Clinton's remarks.

When she finished her speech, some in the crowd stood up to give Clinton a standing ovation. But others appeared to have forgotten they were listening to a speech altogether and were lost on their phones.

Should Clinton become the Democratic nominee, there's virtually no doubt she'll have a lock on black voters in the general election. But that won't mean that some of them don't believe there could be better options.