All the Ways Muhammad Ali Showed Us That Black Lives Matter

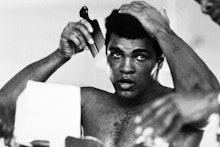

Black boxing legend Muhammad Ali was known as one of the greatest athletes of all time. He conquered the world of boxing in an era fraught with racial tensions and political turmoil. No one could deny his athletic ability, but his pro-black political activism made him a polarizing figure and nearly cost him his career in the late 1960s.

Ali died late Friday night in Phoenix at age 74, his family confirmed to NBC News. Born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky, Ali grew up in the segregated South and experienced racial prejudice firsthand.

Ali's upbringing and conversion to Islam shaped his worldview. He placed a great deal of emphasis on being black, proud and unbowed in the face of discrimination and injustice. Ali's bold political statements during the civil rights era and the protests against the Vietnam War have undoubtedly inspired later generations of social justice and peace activists.

Here's a look at how this larger-than-life sports figure showed that black lives have always mattered, long before young Black Lives Matter activists would turn the idea into a rallying cry nearly 50 years later:

He wasn't just bragging — he was showing blacks how to love themselves.

At the height of his boxing career in the mid- to late-1960s, Ali drew attention for his over-the-top boasting before and after matches. Among his most famous remarks was a colorful description of his boxing style: "[I] float like a butterfly, sting like a bee," Ali said in a 1964 interview before claiming the heavyweight title from Sonny Liston.

Ali also spoke to the political realities of the time, when black people faced blatant and subtle barriers in employment, housing and the voting booth. In 1967, Ali, delivered a speech titled "Black Is Best" to students at Howard University, the historically black college in Washington, D.C. He blasted what he described as a black inferiority complex, the psychological conditioning in which blacks sought out white society's approval:

See, we have been brainwashed. Everything good and of authority was made white. We look at Jesus, we see a white with blond hair and blue eyes. We look at all the angels, we see white with blond hair and blue eyes. Now, I'm sure if there's a heaven in the sky and the colored folks die and go to heaven, where are the colored angels? They must be in the kitchen preparing the milk and honey. We look at Miss America, we see white. We look at Miss World, we see white. We look at Miss Universe, we see white. Even Tarzan, the king of the jungle in black Africa, he's white! ... Black dirt is the best dirt. Brown sugar causes fewer cavities, and the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice.

His words positively altered the self esteem of generations of black people, including President Barack Obama and first lady Michelle Obama, who saluted Ali. "That's the Ali I came to know as I came of age – not just as skilled a poet on the mic as he was a fighter in the ring, but a man who fought for what was right," the Obamas said in a statement released Saturday by the White House. "[Ali was] a man who fought for us. He stood with [Martin Luther] King and [Nelson] Mandela; stood up when it was hard; spoke out when others wouldn't."

He held true to his religious, cultural and political convictions.

Still known as Cassius Clay in 1964, Ali converted to Islam and joined the black Muslim group Nation of Islam. He later legally changed his name to Muhammad Ali and became a minister, and worked with civil rights icon Malcolm X to expand the Nation of Islam's national influence. In response to racial discrimination, the group controversially preached Black Nationalism, encouraging black people to forge paths independent of influence by European social and cultural norms.

During this time, the U.S. was at war in Vietnam. Selective Service laws meant that Ali and many other black men were eligible for the draft. Indeed, the boxer was drafted in April 1967. Declaring himself a conscientious objector to the war, Ali refused to serve. Boxing officials stripped him of his world title and barred him from boxing for three of his prime years. He was arrested for draft dodging and convicted, a felony.

When asked by reporters why he'd seemingly given up everything to oppose the war, Ali said, "My conscience won't let me go shoot my brother [in Vietnam] or some darker people or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America."

He continued: "And shoot them for what? They never called me n*gger."

Ali appealed his felony conviction, which the U.S. Supreme Court overturned in June 1971.

His integrity attracted other black athletes to the cause.

Before his draft-dodging trial, other top black athletes rallied around Ali in what has become known as the Cleveland Summit. Then-retired Cleveland Browns football player Jim Brown met with Ali. So did Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Carl Stokes, John Wooten, Willie Davis, Sid Williams, Walter Beach, Curtis McClinton and Jim Shorter.

After a three-hour meeting, the athletes announced in a press conference that they supported Ali, marking one of the first occasions that a group of the nation's top black sports stars made a joint political statement. "We didn't care about any perceived threats [to our careers,]" Wooten told Cleveland Plain Dealer in 2012. "We weren't concerned because we weren't going to waver. We were unified. We all had a real relationship with each other and we knew we were doing something for the betterment of all."

The influence of that moment could be seen last year, when members of the University of Missouri football team refused to take the field in support of a hunger strike and protest over racial discrimination and animosity toward black students. The players' decision led to the resignation of the university's president last fall.

Ali continued his friendship with the group of athletes who stood behind him. In 2014, Ali, Russell, Brown and others reunited more than 45 years after the Cleveland Summit, at the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville, Kentucky. Brown received the Muhammad Ali Humanitarian Award that year.

As news of his passing spread Friday night, activists within the Black Lives Matter movement poured out messages of appreciation for Ali and his activism. Here are just a few:

June 6, 2016, 9:51 a.m. Eastern: This story has been updated.

Correction: June 4, 2016