This Gay Filmmaker Made a Movie in One Of the Most Homophobic Places On Earth

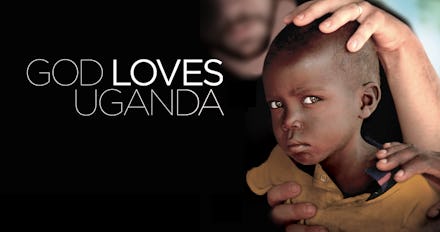

On Dec. 3, 2013, God Loves Uganda — a searing indictment of evangelical Americans' role in the spread of homophobia abroad — was announced as one of 15 films to be shortlisted for this year's Best Documentary Feature Oscar.

Seventeen days later, Uganda's infamous "kill the gays bill" finally made its way through parliament, having stirred up international outrage ever since its introduction in 2009. If signed by President Yoweri Museveni, consenting adults could face up to 14 years in prison for engaging in homosexual acts, and be jailed for life for repeat offenses.

As LGBT activist Rev. Kapya Kaoma says in God Loves Uganda's opening moments, "If we don't move fast, I foresee a lot of death happening."

The film's Oscar-winning director Roger Ross Williams, who is gay and grew up as a member of the African American Baptist church, first set his sights on Uganda upon learning that the overwhelmingly Christian nation is the premier destination for American missionaries; half of Uganda's population is under the age of 15, making it a promised land for evangelicals seeking impressionable new converts.

Around the world, there's a global homophobia that's spreading.

Williams followed prominent (and vehemently anti-gay) religious leaders like The Call co-founder Lou Engle and controversial pastor Martin Ssempa, African activists (including David Kato, who was beaten to death during filming), and a group of bright-eyed young missionaries from Kansas City's International House of Prayer ("IHOP") to uncover how the American evangelical right has ignited intolerance across the Pearl of Africa — intolerance that has led to the demolition of successful safe sex programs and contributed to Uganda's becoming one of only two African nations where AIDS rates are on the rise.

I spoke with Williams about being a gay filmmaker in Uganda, the problem with millennial missionaries, and near-death experiences at the hands of pastors.

A young man mourns at the funeral of David Kato, Uganda's most outspoken gay rights advocate.

Julianne Ross [JR]: When you were filming, did you think it was likely that the Anti-Homosexuality Bill would actually pass?

Roger Ross Williams [RRW]: That was always a looming threat. The bill sort of held as this way of threatening and distracting both the international community and Ugandans, so you never knew if they were going to follow through. It was pretty shocking when it actually did pass by the parliament.

JR: Can the film be shown in Uganda? I would assume based on the provisions in the bill that it can't at this point.

RRW: No, I can't show the film there. There's a provision in the bill against the "promotion" of homosexuality. It's an extremely hostile environment, and there's no way I could have a public screening.

They all surrounded me and said, 'We know you're gay.' And these are men who believe that it's God's will to kill gay people.

IHOP Meeting in Kampala, Uganda. Image credit: Roger Ross Williams.

JR: Had you been planning to focus on the actions of American missionaries from the start?

RRW: I knew that they were playing a certain role, but I didn't know the extent of it until I got deeper into the story. When I first went to Uganda on a research trip, the first person who I met was David Kato. And David said to me, "There are lots of stories about the activist community, but no one has really told the story of the damage that religious fundamentalists from America are doing in our country." He really inspired me to move forward with that story.

IHOP is a church of young people, of millennials. Many of them have come from troubled pasts, drugs, broken families. They found this sense of community, and they get lost in that.

JR: All of the activists' bravery was incredible. To be so outspoken in that environment was just a really inspiring thing to see.

RRW: Yeah, it's unbelievable. It's mind-boggling. They're just fearless. In the little time I spent with David Kato, he was terrified for his life, because he had — they all had — been beaten, and harassed, and threatened. But they just refused to back down. They loved their country, and were like, "We're not going any where. We're Ugandans and this is who we are, and you have to accept us."

Ugandan Bishop and LGBT rights activist Christopher Senyonjo, who was excommunicated from the Church of Uganda for his refusal to denounce homosexuality.

JR: Did you ever have any moments when you felt unsafe while filming?

RRW: Absolutely. There were many, many moments! [Laughing] But the biggest moment came when I was outed by one of the Americans in the film. She wrote about me on her blog, and someone sent her an email saying that I'm gay. And she sent that email to all of the anti-gay pastors in Uganda. I had been spending a lot of time with them, so they invited me to dinner and it was an ambush. They all surrounded me and said, "We know you're gay." And these are men who believe that it's God's will to kill gay people.

I was with my crew, and we were all terrified. They said that they had Googled me, and they had found that I won an Academy Award. They said that I was probably too high profile, and they were going to cure me. So they started laying hands and praying over me. And I just went with that!

A woman prays at IHOP in Kansas City, MO.

JR: Have any of the people who were in the film reached out to you since it premiered? What was their response after seeing it?

RRW: Yeah! We brought [IHOP Director of Media] Jono Hall and Stuart [Greaves, a Senior Leader at IHOP] to New York and showed them the film. I was pretty nervous, but what was great was that afterwards we sat down and had a four-hour conversation. Stuart said it made him more sensitive to the way they spread their message. Jono was a bit more defensive.

Jono Hall, IHOP Media Director.

Jesse Digges [founder of Digges mission base in Uganda] showed up at a screening in New York that just happened to have been adopted by immigrant gay theologians. So Jesse stood up there and started really to defend [anti-gay pastor] Scott Lively, which was kind of indefensible. [Lively is currently on trial for crimes against humanity for his involvement in Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill.]

But then one of the audience members said, "Do you understand that you are in Chelsea, New York in an audience of gay theologians? Gay men who understand the Bible?" And Jesse goes, "Well, I pray for you all and I pray for your salvation." I stood back and they just tore into him. It was pretty intense.

Jesse and Rachelle Digges, founders of Digges Mission Base in Uganda. Image credit: Derek Wiesehahn.

JR: The young missionaries seemed like they genuinely believe they were doing good work, but at the same time they came across as very naïve. Do you think they had any idea of the repercussions of their actions on Ugandan culture?

Young IHOP missionaries sing with Ugandan locals.

RRW: There's a lot of naiveté there. It's what they've been told by the adult leaders in IHOP, that they're in a spiritual war to eradicate sin. They're looking for an adventure. That's the thing I wanted the film to do. They need to understand the repercussions of what they're doing, that they're going into a culture that is very different than the Middle America they come from.

One after another people lined up to come out publicly to the pastors. And something miraculous happened at the end.

IHOP is a church of young people, of millennials. Many of them have come from troubled pasts, drugs, broken families. They found this sense of community, and they get lost in that. But I think the leaders have a master plan. [IHOP leader] Mike Bickle was on the ground in Uganda the day Idi Amin fell from power. And he said, with bullets flying over his head, that there was a group of evangelicals to take that country as a Christian nation. [The adults are] well aware of what they're doing, but the kids are the innocent foot soldiers.

JR: They didn't seem to know what they were doing, and then just seemingly by virtue of them being American, people listened to them.

An IHOP missionary preaches to a Ugandan woman.

RRW: Exactly. If you notice [one of the missionaries] says [to a villager], "I've come all this way on an airplane." You know those women sitting in that village have never left Uganda, and have definitely not been on an airplane. So it's intimidating. You see this woman sitting on the ground, and this 20-year-old girl from the Midwest hovering over her saying, "We've come here." They represent everything that America represents, wealth and power. It's imperialism. It's colonialism.

Rev. Jo Anna Watson has been traveling to Uganda as a missionary since 2002. Image credit: Derek Wiesehahn.

JR: Have you shown this film — obviously not in Uganda — but elsewhere in Africa, and what has the response been to it?

RRW: Yeah, we did a whole African tour with the film, which was an unbelievable experience. There was a moment in Malawi when we were screening to about 80 members of the faith community and about 40 LGBT people, but every single one of them was in the closet because you couldn't be openly gay in Malawi. We had a conversation afterwards, and the pastors immediately stood up and started saying [gay people are] worse than dogs, the usual stuff you hear. They were really angry and worked up, and cheering each other on.

And then a gay man, who was very nervous and scared, walked down to the microphone. He was shaking, and you could hear the quivering in his voice. He said, "I was born this way, and my life has been so horrible. If I could change I would, but I can't." He addressed the pastors, which was so powerful, and he said, "You have made my life a living hell."

A Ugandan man protests homosexuality at a church meeting.

Then a woman came down, and she said, "I'm married with two kids and I love my children, but I don't love my husband because I'm a lesbian. And you have forced me to live a lie." And then her girlfriend came down and they kissed! That just got all the gay people going crazy, they started cheering and jumping up and down. It was this incredible moment because no one had ever come out publicly in Malawi. Then just one after another people lined up to come out publicly to the pastors. And something miraculous happened at the end.

One of the first pastors who'd been saying all this anti-gay stuff stood up and said, "I had never seen a gay person, I didn't think you were so human. I just thought of you as monsters. I take back everything I've said. I want to recant my statement, and I want to say that now that I see you I think that gay people are okay." It was unbelievable. We were all in shock.

A Ugandan man prays at "The Call" Uganda, a Christian prayer movement brought to the country by Lou Engle and Rev. Jo Anna Watson.

JR: So what's the next step? What can people who see this do to help?

RRW: So much money flows from American churches [to Africa], but a lot of parishioners don't know that their money is going to fund hatred and intolerance. We have a campaign called Keep Hate Off the Collection Plate, for parishioners to question their pastors about where their funds are going. We also have a petition for the U.S. government. A lot of government money is administered by faith organizations on the ground, so HIV and AIDS funding in Uganda never reaches the LGBT community. [The petition] is about the U.S. government holding organizations accountable for where that money is going in Uganda so that they are not excluding LGBT people from treatment.

JR: Another thing that struck me was the scene where Rev. Ssempa is showing pornography in the church. It's so absurd it was almost like satire. I just kept thinking, he can't honestly believe this. Was this consciously a performance?

Rev. Martin Ssempa shows an S&M video to parishioners.

RRW: Ssempa is a performer. But those theatrics play very well in Uganda. For us, it seems totally absurd. Uganda — people need a distraction. Uganda has one of the highest rates of corruption in the world, so people are looking for a scapegoat, for someone to blame all their problems on. If you go to the streets of Uganda and you say, "What would you do if you saw a gay person?" I guarantee everyone you ask would say something like, "I would try to kill it." It. That's how crazy it is. But it's not about the gay person. You demonize these people and you make them not human, and people put all their anger, all their frustration into that "evil."

A street preacher in Kampala, Uganda. Image credit: Derek Wiesehahn.

The world is paying attention. It's happening all across the African continent, and I think that if we ignore that, we're going to have a huge problem on our hands. It's like history repeating itself. There's an impending sort of genocide of gay people, and it's not just in Africa. You see it happening now in Russia, in India. Around the world, there's a global homophobia that's spreading.