How Close Are We Really to Finding Life in Outer Space?

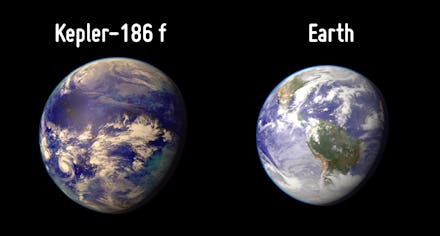

NASA's recent discovery of Kepler-186f, the first habitable Earth-sized planet is big news in humankind's long search for extraterrestrial life.

A universe full of exoplanets: Thanks to the Kepler Space Telescope, which was launched in 2009 to hunt planets across the universe, we've managed to find around 1800 exoplanets so far, many of which have been discovered in just the last year or so.

Image Credit: NASA

Kepler has had so much success because it's the first piece of space technology that is remarkably adept at detecting tiny changes in light coming from distant stars. The small, periodic dimming of a stars light is the classic smoking gun which scientists use to find exoplanets.

Image Credit: NASA

The long-held Holy Grail for planet hunters has been to find a world which is the Earth's "twin" and therefore thought to be capable of supporting life.

Kepler has advanced this cause amazingly so far, managing to find many planets that are a similar size to our Earth. In fact, thanks to Kepler, we now know that the Earth-sized planets are actually quite common in our galaxy.

Image Credit: NASA

The bad news? Most of the Earth-sized planets found so far are either too hot or too cold to support life. For instance Kepler-20e, the first Earth-sized planet discovered, has an extremely small 6-day orbit, making planet's surface temperature is an inhospitable 1,400 degrees.

Image Credit: NASA

On the other hand, the Kepler telescope has also discovered many planets within the "habitable zone" of star systems. This is the region where planets may be at the correct temperature to support liquid water. However, many of these planets such as Kepler-22b, the first habitable-zone exoplanet discovered, are several times the size of Earth. Unfortunately, these "Super-Earth" sized planets are unlikely to be rocky like our home, and are probably composed of liquid or gaseous outer shells.

Image Credit: NASA

Our first exoplanetary relative: Kepler-186f is the first exoplanet discovered that is both the right size and distance from its own sun, making it the best candidate for supporting life so far. That's exciting news.

Image Credit: National Geographic

The size of Kepler-186f, which is within 10% of Earth's, is particularly encouraging. Although scientists don't have direct evidence of the planet's composition, observations and models of other exoplanets suggest that planets similar in dimensions to the Earth are most likely to have a rocky composition. This can be seen with similar planets within our own system such a Venus or Mars.

Image Credit: NASA

We've actually found exoplanets in habitable zones that are as small as 1.5 times the size of Earth before, but the models predict that the chances of a rocky planet increase significantly the closer you get to the Earth's size, making Kepler-186f the most exciting exoplanet discovery to date.

What's next? Right size, right distance. Great news, but these characteristics alone don't guarantee that a planet is habitable. There's other crucial information that we need before we can be confident in launching future space-probes on long journeys to strange star systems in search of life.

One of the most important things that we need to know is what the atmospheres of exoplanets such as Kepler-186f are composed of. The atmosphere plays a crucial role in habitability in many ways such as protecting the surface from solar radiation, and by regulating the planet's temperature. Its significance can be seen in a planet like Venus, which is a similar size to Earth and orbits within the habitable zone, but has a greenhouse-filled atmosphere that renders it far too hot to support life.

So how can we find out more about the atmosphere of exoplanets? Well, in 2018 we're sending an exciting new telescope into space that can do just that. It's called the James Webb Space Telescope, and its mirrors are an impressive 7 times larger than those of the venerable Hubble Space Telescope.

Image Credit: NASA

The telescope will help decode planetary atmosphere by observing changes in light when a planet passes in front of a star. When this happens, the light changes because certain wavelengths are absorbed by the chemicals in an exoplanet's atmosphere. The gaps that appear in the spectra of the star's light are therefore a cosmic fingerprint that can reveal just what the atmosphere is made of. Because this absorption effect isn't particularly strong, it will take a powerful telescope capable of seeing in infrared like the James Webb to observe them.

Image Credit: NASA

So does this mean that we can confirm that Kepler-186f is actually habitable soon? Sadly that seems unlikely, even with the James Webb. The Kepler-186 system is 500 light-years from Earth. This means that the light from its star is too dim to gather the detailed light signatures needed to decipher further details about the exoplanet.

But we're sending up another piece of high tech space equipment that could help. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) will be launched in 2017 to conduct an all-sky survey to find exoplanets in our solar neighborhood. The stars that TESS will scan are 30 to 100 times brighter than those surveyed by the Kepler satellite, so we'll be able to quickly learn more about an exoplanet's composition soon after it's first discovered. With its wide-field cameras, TESS will cover an area of the sky 400 times larger than Kepler.

Image Credit: MIT

Because Kepler has shown that Earth-sized planets are relatively common, it's expected that Kepler-186f is just the tip of the iceberg, and we'll soon find hundreds more similarly sized planets orbiting the habitable zones of stars. Future space missions will allow us to find out a lot more about these planets than just their locations, and may even help us to directly detect the bio-signatures of life, such as the presence of water, oxygen, or even photosynthesis, on other planets.

Image Credit: Harvard

And just like that, our place in the universe may suddenly appear to be little less lonely.