The Author of 'I Know What You Did Last Summer' Fell Tragically Victim of a Real Life Murder Story

Murder two ways: You probably haven't heard of author Lois Duncan (real name Lois Arquette) or the untimely murder of her teenage daughter Kathryn Arquette. But you most certainly have heard of the 1997 cult thriller, I Know What You Did Last Summer.

Under her pen name, Duncan wrote the 1973 book that went on to inspire, I Know What You Did Last Summer featuring '90s girl-next-door actress Jennifer Love Hewitt, Buffy star Sarah Michelle Gellar, Freddie Prinze Jr. and heartthrob Ryan Phillippe. Along with Scream, it was the quintessential '90s horror flick.

But unlike other suspense thrillers of that era, or any era for that matter, the real meat of this story isn't what appears on screen or in the pages of Duncan's book. Rather it's the enigmatic way Duncan's daughter was murdered, the possible police cover-up and the elusive assailant(s) and potential gang affiliations that were discovered in the aftermath. This is not her E! True Hollywood Story. This is her real life.

The plot of the film is loosely based on Duncan's book. Both follow high school teenagers who accidentally kill a man in a hit-and-run and make a pact to never tell about it. Eventually, the teens find a worrisome note saying, "I know what you did last summer," — hence the eponymous book and film titles.

The film went on to gross $125 million. Duncan, who wasn't involved with the Hollywood adaption, was still knee deep into crime-solving her daughter's 1989 homicide when the film hit theaters. In a bizarre twist, Duncan, who has authored several young adult suspense novels, became the protagonist in her own real life crime saga after the events of July 16, 1989.

Image Credit: Columbia Pictures

Life imitates art: BuzzFeed contributor Tim Stelloh reported on the mysterious death of Kaitlyn Arquette, or Kait as she was known, and Duncan's steadfast pursuits of identifying her daughter's killer.

On the night of the event, 18-year-old Kait had just graduated high school. After watching Valley Girl at a friend's house, she drove her '84 Ford Tempo at 10:45 p.m. through downtown Albuquerque. She was shot with two bullets to the head that entered through the driver's window. Kait died the following evening.

Duncan has spent the last 25 years deciphering the possible motives and assailants related to the attack. While the police later determined the crime was a random act of violence, Duncan found evidence that pointed elsewhere.

Probable cause? Kait's boyfriend at the time was Dung Nguyen, a Vietnamese immigrant. He was initially dismissed as a suspect because his fingers tested negative for gun residue. The police found a letter from the victim in the apartment she shared with Nguyen, saying, "Hon, where are you. I know you're still mad. I'm so sorry OK! I miss you today. I went to mom's house to return these books. I'll see ya. Love." A lover's quarrel was ruled out as motive then.

Five days after the murder, Nguyen was found with stab wounds to his stomach when he claimed he was trying to commit suicide. Curiously, people committing suicide rarely self-inflict stabs wounds in their stomach. But the curious case of Nguyen doesn't stop there.

At the time, Nguyen was involved in insurance fraud in Southern California, where scammers would stage car accidents to claim the insurance money. He would sometimes bring Kait with him to California. Duncan claims that as Nguyen was in the hospital recovering from the stabbing, he told her that he didn't kill Kait but that he was "deciding" whether he loved Kait enough to tell who did. (He never admitted to knowing if he did know, just that he was deciding.) Also, the Alberque police department knew of Nguyen's illegal activity, but were never concerned and did not even follow up about possible Vietnamese gang affiliations.

The puzzle surrounding Nguyen escalated for Duncan when she later discovered that the note from Kait and Nguyen's shared apartment was not in her daughter's handwriting and was clearly misspelled, which was out of character for Kait. Also, Kait's friend claimed that Nguyen called her the night of the murder screaming, "Kait['s] dead!" But "the police didn't notify Nguyen of Kait's murder until 3 a.m. — several hours after [the friend] had that panicked conversation with Nguyen," reported Stelloh.

Charges Dismissed: Two men, Miguel Garcia and Juvenal "Juve" Escobedo, 18 and 21 years old, were arrested in 1989 as the perpetrators. Authorities claimed it was a random drive-by shooting — Escobedo dared Garcia to shoot the victim and he did so. Even though many, including the district attorney Robert Schwartz, believed the two to be guilty, there was barely any evidence or a viable motive. A jury eventually dismissed the cases against Garcia and Escobedo.

An overlooked detail: Duncan blames the disorganized and possibly incompetent police officers for missing a key detail in the case, which was only discovered by private detective Pat Caristro later.

On the night of the murder, the first detective on the scene found Paul Apodaca standing by Kait's car, who claimed to be just passing by. According to Caristo, "standard procedure would have required police to run Apodaca's name," which they did not.

If they had, they would have found that he was "charged with committing multiple violent attacks against women, including robbery and beating a young girl with a baseball bat," wrote Stelloh. Apodaca's car was matched the make and model, though not the color, of eye-witness testimony of the type of car that left the scene after the crime.

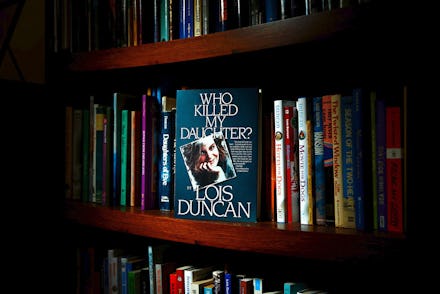

Curious speculation: The case consumed Duncan for years. Duncan turned to psychics, Caristo and crime scene evidence to help unfold the narrative. She even wrote two books revolving around the ordeal: Who Killed My Daughter? and One to the Wolves.

At one point, Duncan met with a psychic that oddly resembled a character from a suspense novel she wrote years before meeting the actual psychic. "I had the crazy feeling I had scripted the story of my own future," Duncan wrote.

Stelloh suggests that Duncan raised questions with obscure answers. "Was there a relationship between Apodaca, the 'Vietnamese connection' and Escobedo and Garcia? Had the crime scene been derailed by incompetence or by a cover-up? Had Kait stumbled onto something even more sinister than insurance fraud?"

Sadly, Duncan does not know the answer to these questions. Nor does she know who is to blame for Kait's murder.This case, unlike her novels, is an ongoing investigation.