The Fascinating Science of What Dreaming Does to Your Brain

This story was written independently by our editorial staff prior to Mic's partnership with GE.

As you're falling from the roof of a skyscraper to your almost-certain death, all of a sudden you realize you can fly. And then, just as you're whizzing over lush treetops and taking in the fresh, cold air filling your lungs, you wake up.

Dreams are often emotional; sometimes they even seem real: A frantic escape from a dungeon filled with angry nanobots can leave you spooked for the rest of your day. A pleasant dream, similarly, can make us feel happy.

But what purpose do these trips to pseudo-reality serve?

Scientists are well on their way to answering those questions. Most of their knowledge of our dreams comes from what they see on an electroencephalogram (EEG), the read-out of navy blue lines that displays the electrical dance of brain activity.

Image Credit: University of North Carolina

As we fall asleep and become less perceptive of the outside world, scientists have found, our brain gets quieter: Its electrical signature changes from short jagged hiccups to longer rolling waves. Even after we start to enter deep sleep, we still get interrupted, periodically, by stuff around us. Eventually, we succumb to a deep slumber. This is REM sleep, the time for dreams.

Image Credit: Nature

1. We dream to learn.

Scientists have been debating the purpose of dreaming since the 1970s, when a team of Harvard psychiatrists said it was meaningless. They were shortly outdone by a group of evolutionary psychologists who said dreams served an evolutionary purpose. Dreaming was our ancestors' way of gearing up for a fight, they said. While we sleep, we simulate potential threatening situations and work out how best to react.

Despite the conflicting theories on its purpose, we all know a good night'’s sleep improves learning and memory. Animals dream, too.

This month, a team of scientists in China and the U.S. studied mouse brains to see how they process new information while they sleep. After teaching a group of mice a new skill, they divided them into two groups where one slept and one didn't. In the brains of the sleeping mice, new connections between neurons in the brain had sprouted that weren't there for the mice that hadn't slept. Deep sleep, the period when most dreams happen, was also the time most of the connections were formed. During REM sleep, the mice were replaying the day's activities, the researchers say, committing the newly acquired skills to memory

2. We dream to deal.

After a particularly trying day, many of us need time to "process." But despite our attempts to think through stressful or infuriating situations while awake, much of our emotional processing may take place after we hit the pillow.

"Dreaming diffuses the emotional charge of [an] event and so prepares the sleeper to wake ready to see things in a more positive light, to make a fresh start," writes sleep researcher and psychologist Rosalind Cartwright.

When people don't get REM sleep (meaning they don't dream), they also have a harder time processing complex emotions during the day. If problems sleeping persist, scientists show, it can also lead to depression and anxiety, especially amongst children.

3. The way we dream and process memories is surprisingly similar.

Cristina Marzano and a team of scientists at the University of Rome wanted to investigate how humans remember their dreams. Her team showed that our brains exhibit the same activity patterns while dreaming as when we form memories while awake. This means that the way we process memories is similar to the way we dream.

In another study, researchers at France's National Institute of Health and Medical Research demonstrated that people who remember more of their dreams have more spontaneous brain activity in the middle of the front quarter of the brain and in the section of the brain where the temporal and parietal lobes meet, an area of the brain involved in noticing external stimuli.

This makes sense: People who remember their dreams are also easily and frequently awoken, and it is during wakefulness that our brains are capable of memorizing new information.

4. We can control our dreams.

If you're like most people, you don't dream lucidly. That means that when you're dreaming, you're not aware of it, so you can't make decisions that would control the outcomes of your dreams — like choosing to run in front of a speeding car because you know it's all make believe or jumping from a building because you decide you want to fly.

Until recently, scientists couldn't make people have lucid dreams. That is, until a team of scientists zapped the brains of a group of sleeping volunteers with varying levels of electricity. Since the brain's synapses are electric, the technique amplified the signals already present in people’'s heads.

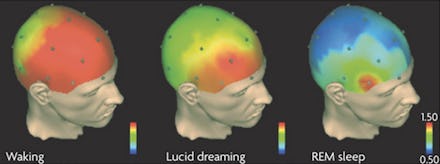

When most people dream, their brain activity is fairly calm. Lucid dreaming, however, amps up our brain waves to the highest levels recorded — 40 Hz. Amongst the volunteers, the ones who received that exact amount of electricity dreamt lucidly the most.

Image Credit: Science Illustrated

5. Scientists are working on decoding our dreams.

Scientists recently managed to correctly identify the type of objects people had seen in their dreams using a dream decoder. It sounds sci-fi, but it's a bit more practical than you might think.

The researchers had their participants watch a video montage of hundreds of images. While the viewers watched, the researchers had a computer record the patterns of electric signals exhibited by their brains. With each image, they found, the brain displayed a unique signature. Then they let them sleep. When they woke them up, they hooked them up to the decoder and asked them what they had been dreaming about.

The machine accurately selected the objects they'd seen in their dreams — to an extent. If someone said they had dreamt about a Schwinn, for example, the machine would have told them she'd dreamt of a bicycle, but wouldn't have given them the specific brand.

6. You can have several — even a dozen — dreams in one night.

We dream about every 90 minutes, with each cycle of dreaming playing out longer than the last. Most people have at least four to six dreams each night during the REM portion of sleep alone. During your lifetime, you can be expected to have about 100,000 dreams.

7. Bad dreams can make us more anxious the next day.

Can having a nightmare make us antsy during the day? Perhaps. An Australian study of more than 600 high schoolers found that the students who were upset by their dreams were more likely to suffer from general anxiety than those had pleasant dreams. When the researchers controlled for distressing events occurring in students' lives — such as parents' divorce — the effect remained.

Thinking they could disprove the researchers' findings, another group of scientists showed disturbing images to a group of volunteers (some who got REM sleep and some who didn't) before bed. In the morning, they had the subjects look at the images again. Those who got REM sleep (meaning they had the chance to dream) were more emotionally triggered by the images, while those who hadn't slept were not as affected.