'Esquire' Thinks Women Make Great Fashion Accessories — But Watches Are Better

"The style makes the man," according to Esquire. In the context of this aphorism, apparently, women are men's finest fashion accessory — well, one of them, at least.

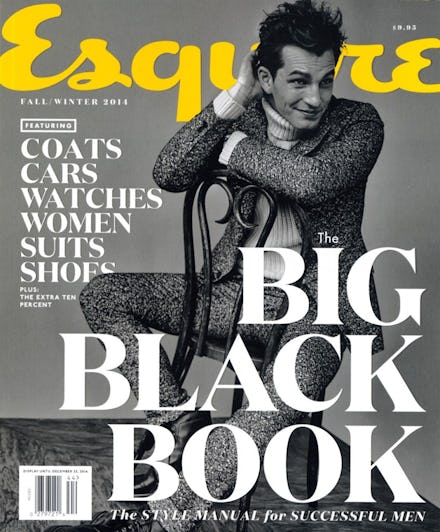

The magazine's fall/winter 2014 cover aims to portray "Man at His Best, All Day Long," with its new "style manual for successful men." To that point, the stylish black and white cover advertises the latest must-have's for men this coming season: "Coats, Cars, Watches, Women, Suits, Shoes."

That's right, in the pantheon of Esquire style, females rank somewhere between that hot new peacoat and the latest Italian leather loafers.

Perhaps the first question should be: Why are women fourth on the list, behind watches? Oh, that's right, because as "arm candy" we go on both men's arms.

Feminist blogger Amanda Hirsch is having none of it.

Esquire, which has attempted to cultivate a reputation as one of the more sophisticated men's glossies, really missed the mark with this. Here is a perfect example of advertorial sexism at its finest: Women are categorized like consumer goods, items to purchase, just like coats or shoes. Because they are commodities, this type of language also leads to women being fetishized and commercialized to the point that the become interchangeable with other consumer goods.

To everyone's detriment, this is how men are still too often marketed to. Just look at this ad for "Tom Ford for Men:"

Or this one:

The issue here isn't capitalism, or the age-old marketing instinct that "sex sells." This is about sexism ruled by the objectification of women's bodies to drive the market.

Not surprisingly, this isn't the first time Esquire has regarded women as commodity fetishes or intriguing objects of analysis. In April 2006 they offered "Women: The Manual."

Then there's this thoroughly unenlightened 1967 cover, which claims that women are "through," well-worn goods that are no longer desirable, by the age of 21:

Esquire's perpetuation of the sexist objectification of women needs to be called out for what it is. But it also represents an opportunity for us to re-evaluate what drives the market economy: Can we sell sex without sexism? Can men be stylish without "using" women to accessorize their latest suit?