Musical Genome: Third Eye Blind On Their First Album, Bowie and How Music Shapes Us

One sweaty Sunday in July, my best friend Hannah and I are speeding down highway 27 West heading home from my DJ gig in Montauk, New York. The '90s Sirius station has blared for the last 45 miles, and our hungover heads bob lightly to the sounds of our childhood. Suddenly, a drum intro punctures the haze and gives us both the rush that only a song you've known forever can. Our faces whip towards one another's like magnets. Third Eye Blind's irresistible "Semi-Charmed Life" is on, and it demands harmonies.

"I'm packed and I'm holdin! I'm smilin'/ She's livin'; she's golden; she lives for me." We spew the rapid-fire verse in unison, royally messing up a good portion of the words. "Says she lives for me/ Ovation, her own motivation/ She comes 'round, and she goes down on me!"

"You know," I scream over the radio. "It's because of this song that I know what going down on someone is!" Hannah laughs. My mind begins weaving through all the other memories I have attached to this song. I have many.

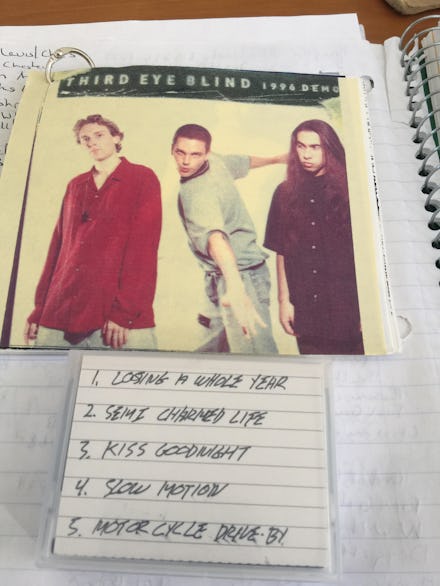

My dad used to represent the band and its lead singer, Stephan Jenkins, when I was a kid. He played it for me when the song just a long-shot demo. I loved it then, and it's still close to my heart. In fact, I begin to think, if one were to trace the development of my tastes and career, it might all lead back to here. Does everyone have an equivalent song in their past?

Hannah turns to me again, and the chorus' lyrical coda jolts me out of my reverie, "Goodbyeeeeeee!!!!"

When I get home later that day, Third Eye Blind, Stephan and all the nostalgia attached to his music weigh heavy on my mind. I put on the band's first album, one of the first I ever loved, while I unpack.

As it unspools, I suddenly have complete clarity on why I love music, why it's so fundamental to my very existence. Since my 3EB days, music has gone on to be my life. It's ushered me through all my personal transitions, from a closeted, chubby, Jewish middle-schooler; to a shut-in, gay, pop-music nerd-cum-college stoner; to a New York club DJ; and now a writer who writes primarily about pop music.

This album isn't separate from me. The rock, hip-hop and pop all artfully mixed within its 14 tracks correspond precisely with my tastes today. Moreover, I recognize Stephan's presence in my childhood as a critical piece in my life's story. "Songs" or "album" feels too slight to describe this music. They're more like fibers or atoms. They're part of my very foundation.

Is Third Eye Blind is that good, that powerful? Or was being there the reason this music feels like a piece of my soul? I think about reaching out to Stephan. I wonder if he remembers me being around in those days too. I wonder if he can explain to me why his music cuts so deep.

"I've always found the process of songwriting painful. I'm one of those people who's lyric-focused, and if they're not right, they're wrong."

"Of course I remember you being around!" Stephan said reassuringly when I called him on a freezing January day (freezing for me, anyway; Stephan still lives in his beloved San Francisco). "Your dad was really our only major music business connection at the time."

Stephan's business association with my dad, who started his own entertainment law practice — Selverne, Flam and Mandelbaum — when I was seven, came via the most unlikely of sources: my grandmother Barbara. "Babu," as she's fondly known inside the clan, was at a wedding in the San Fransisco's Bay Area when she struck up a conversation with the band's then-manager, Eric Godtland.

The minute she ascertained that Eric managed a rock band, she bragged all about her son-in-law, the music attorney. Then she called him. "Tim, you have to hear this new band, The Third Eye Blind," she asserted.

When I called her about this story, I asked, "Babu, do you realize you're a crucial lynchpin in Third Eye Blind's success?"

"I am not the reason for anything," she insisted.

"'Semi-Charmed Life,' 'I Want You,' those were some of the first songs I ever wrote. It was just me, sitting on my bed, writing songs," Stephan told me about his early forays in music. "I really started Third Eye Blind so I could do a band on my own terms."

As I've parsed Third Eye Blind's music, I've grown increasingly aware of what an adept writer he is. But it's the combination of his dexterity with language, his ability to articulate in detail, paired with an unwavering lyrical fluidity that makes these songs work. "Semi-Charmed Life" is notable for a sheer plethora of verbiage flying forth, but also for the way in which the listener is never explicitly aware of just how lyric-packed it is. I was surprised to hear, then, that his way with words is the product of toil.

"I've always found the process of songwriting painful," he said. "I'm one of those people who's lyric-focused, and if they're not right, they're wrong."

It dawned on me that at 29, I'm just about the age Stephan was when he was writing those songs. I wondered aloud if the process of making things with words ever gets easier. "Nope. I haven't really gotten any better at it," he said with a chuckle.

"The only guy I've ever heard of who listens back to his old music is Kanye [West]. I'm about looking forward. We've been lucky to be able to continue to have people who care about what we're doing now."

In the 20-plus years since Third Eye Blind's debut, Stephan and the band (in various formations) have recorded four more albums, sold around 12 million copies of them and still tour extensively for an extraordinarily loyal fanbase. Their most recent record, Dopamine, came out in June.

"This newest iteration of the band is the first time I think things have really come together," he said. "We look at each other and we're super in sync."

I explained to Stephan how I couldn't seem to escape his first album, bringing up his much-blogged about iHeartRadio Music Festival performance of "Jumper" with Demi Lovato in September. He seemed mildly pleased, but not like the kind of guy who harps on past successes.

Does he ever listen to that first album, though? "Nope. Never listened to it ever," he asserted. "The only guy I've ever heard of who listens back to his old music is Kanye [West]. I'm about looking forward. We've been lucky to be able to continue to have people who care about what we're doing now."

Maybe the art we first consume is more important to us than the art we first create.

Research suggests that some songs, no matter how many times you hear them, have the power to call forth the free, unencumbered kid who first heard it. "Music lights these sparks of neural activity in everybody," Slate writer Mark Joseph Stern explained. "But in young people, the spark turns into a fireworks show. ... The music we love [then] seems to get wired into our lobes for good."

The massive amount of hormones surging through our bodies at that time wire certain songs into our very identities. "[These songs] didn't just contribute to the development of your self-image," Stern wrote. "They became part of your self-image."

When I asked Stephan about his own Third Eye Blind-equivalent music, the stuff that formed his genome, he mentioned everything from Bob Dylan ("I liked the way he would stretch out space for the verse,") to Cat Stevens' Tea for the Tillerman before moving onto David Bowie.

"The first time in my life that I actually cried, like a wet face full of tears, was when Bowie died," Stephan said. He then spelled out, with perfect lucidity, what hearing David Bowie for the first time did to him.

"A friend played me one of Bowie's records and I was blown away," he said. "[Bowie] was in his whole bisexual, space alien, Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane thing, and my whole world was so wildly parochial. So just to hear that way of singing, the itch, the way he sang 'Oh, oh, oh, oh,' I remember being like, 'What the fuck!?' I had just never heard something so wild, you know?"

As he spoke about Bowie, it was clear how much the late superstar lives inside Stephan. "Bowie said the difference between pop and rock is that in rock, you might get fucked," he continued, with a laugh. "And I always got that, from the first time I heard it, and I've always looked for the subversive. From the beginning, I always come from this place of, 'You've got to say that.'"

I immediately thought of "Jumper" introducing a generation to themes of suicide, "God of Wine" to the perils of alcoholism or "Semi-Charmed Life" and its disturbing accounts of meth addiction. But Stephan is a sponge when it comes to absorbing influences. Growing up and prior to starting the band, he devoured everything from Sly and the Family Stone to Joy Division to Public Enemy. Speaking of his affinity for hip-hop, he said listening to rap pioneers like Sugar Hill Gang made it "natural for me to rap."

If you think about the verses and the phrasing, "Semi-Charmed Life" is, more or less, a rap song.

Let me be clear: It's not that Stephan resents those of us who feel connected to his first record — quite the contrary.

"I remember this tweet I saw recently before a show where this fan was like, 'I hope you'll play "Semi-Charmed Life" tonight because every time I hear it, I know that summer's coming,'" he said. "And I mean, how can I say no to that?"

As our call wound down and Stephan told me about the band's new West Coast tour in support of Dopamine, a solid entry in Third Eye Blind's catalogue, I asked him the question I've been dreading since conceiving this piece.

"The way you feel about Bowie and the way Demi Lovato and I feel about you guys, do you think we'll ever feel that way about any music ever again?" I asked.

He didn't hesitate. "God, I fucking hope so!"

The thing is, we may not. In Stern's piece, he deduces "you'll never love another song the way you loved the music of your youth."

"No matter how adult we may become, however, music remains an escape hatch from our adult brains back into the raw, unalloyed passion of our youths," he wrote. "The nostalgia that accompanies our favorite songs isn't just a fleeting recollection of earlier times; it's a neurological wormhole that gives us a glimpse into the years when our brains leapt with joy at the music that's come to define us. Those years may have passed. But each time we hear the songs we loved, the joy they once brought surges anew."

I'm cool with that. My musical genome may have reached full capacity, but "Semi-Charmed Life" will always, always be another ecstatic car-ride sing-a-long.