A Radiohead fan revisits 'OK Computer', 20 years after he gave up on it

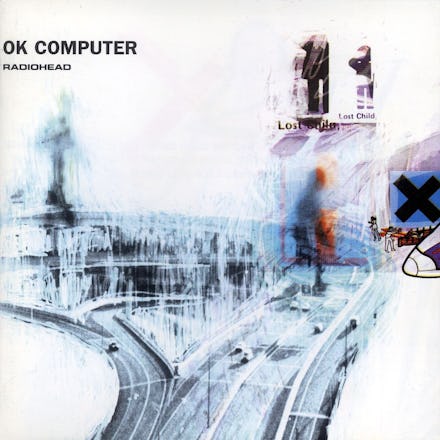

If you're reading this sentence, you probably have an opinion about Radiohead's landmark third album, 1997's world-weary OK Computer. One way or another, you've probably felt something in relation to that suite of songs: the mixture of creeping pre-millennium ennui, consumerist nausea and technological dread that's laced into the record's DNA; the impact of rapturous media hosannas (in Rolling Stone, in Spin, in Entertainment Weekly) the music immediately inspired; maybe a sense of joy or despair over the more overtly experimental turn the British quintet's career had taken. Not I. I spun OK Computer twice in 1997, felt next to nothing, and hadn't felt compelled to revisit the album until this past week, ahead of the 20th anniversary of the album's U.K. release.

When I first heard the record, it was autumn. Princess Diana had recently died in a car crash, on the run from paparazzi. I was early on in my junior year of undergrad, residing in the newly designated creative arts hall at Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland, only vaguely aware of Radiohead's earlier self-loathing radio smash, 1993's "Creep." That single belonged to the Oxford outfit's debut, 1993's Pablo Honey, and was very much in line with that full-length's conventional-enough rock action. By the time of 1995's The Bends, Radiohead had graduated to more theatrical dynamism.

In the fall of '97, OK Computer was shelved alongside Bauhaus and Joy Division CDs in the dorm room of two apprentice goths, who were happy to loan it to me when I asked. The print, online and word-of-mouth praise the album was accruing had gotten to me.

Now, it's important to offer some additional context. Punk and American indie-rock were personal manna in that moment; krautrock, jazz, noise, minimalism, IDM and post-rock hadn't yet become part of my musical diet, and I hadn't yet discovered British avant-garde music mag the Wire. Fast, distorted guitars reigned, basically.

It's also worth noting that it was during this period that I first encountered My Bloody Valentine's 1991 shoegaze opus Loveless as part of a small gathering. I can still recall the shock, the joy, the endorphin-flooded physical shove of that music, along with whose room I was in, where that room was situated in the overall campus geography, and who else was in that room at that moment. I remember this so vividly that it's almost humbling. I may have actually said "whoa" aloud. But reaching for memories of first listening to OK Computer, my mind closes, mostly, on empty space.

All I can remember today is a growing appreciation for "Karma Police," a glorious, mournful single I played ad nauseum despite not fully understanding what it was trying to say. The rest? The rest was vapor. I felt total absence, and a complete lack of curiosity. This was in stark opposition to the era's budding-muso ethos, wherein one might buy an album — Sleater-Kinney's Dig Me Out, say — dislike it immediately, yet play it eight to 10 times to determine why it didn't pass muster before casting the disc into exile. But OK Computer wasn't a CD I merely disliked; it was a CD that didn't even seem to exist, as far as I was concerned.

I listened to the album all the way through twice, each time drifting back to "Karma Police," before returning the disc to whichever of the apprentice goths loaned it to me. I'd climb aboard the Radiohead panic-wagon a few years later with the band's next album, 2000's electronic-driven and impressionistic Kid A, and then fill in the pre-OK Computer gaps around the time of 2003's Hail to the Thief, but I never returned to OK Computer.

This past week, I reacquainted myself with Spiceworld-era Radiohead by degrees: a casual third listen before bed on Friday, then a more focused fourth listen after lunch on Saturday at slightly louder volume.

The third listen confirmed OK Computer as a competent, unremarkable rock 'n' roll platter that traffics in tropes the band would improve upon or explode beyond in later years: shuffling or pureeing melody for effect, departing from traditional songcraft entirely, frontman Thom Yorke nudging his despair into bleaker realms.

As I shrugged along, it became quickly apparent why these songs failed to hold my consciousness 20 years earlier: the grand, stately sweep, the winding theatricality, the sheer, unadulterated Englishness of it all. The velocity was lacking. Perhaps mode of consumption and state of mind played roles as well. At the time, I fancied myself disaffected and cynical, an outcast — but maybe I wasn't quite alienated enough for OK Computer. I was 20 years old in that moment, but perhaps I was too jaded and too social for this record, experiencing these tortured workouts on a boombox in an illuminated dorm room instead of through Discman headphones in a darkened high school bedroom.

In his New Yorker review of Kid A, Nick Hornby hit the nail on the head, albeit an album late. "You have to sit at home night after night and give yourself over to the paranoid millennial atmosphere as you try to decipher elliptical snatches of lyrics and puzzle out how the titles ... might refer to the songs," he wrote. "In other words, you have to be 16." My third visit with OK Computer wound down with me rhetorically wondering what all the fuss was about.

After the fourth spin, I came away feeling slightly more charitable. Sure, opening track "Airbag" remains pretentious, but its effects-flooded, tape-manipulated coda almost redeems it. "Electioneering" is explosive and brilliant. Penultimate tune "Lucky" is almost the Platonic ideal for a Radiohead ballad, spare and angelic, with gentle chords and sleepy effects entangling themselves with Yorke's plaintive vocal. "Subterranean Homesick Alien" and "The Tourist" are no less boring in 2017 than they were in 1997.

The record's unsettling spoken-word interlude, "Fitter Happier," strikes right to the heart of the album's reason for being, succinctly encapsulating a particular horror: of a life drained of spontaneity and personality, of humanity sacrificed to technology and prescription. "Paranoid Android" definitely endeared itself to me, not least because of how casually it weaves genres together — folk, funk and prog, even heavy metal — into a coherent, surprisingly moving whole. "Karma Police," of course, is still "Karma Police" — but it sounded different to me. It felt of a piece with a surrounding album I could better appreciate, a dark jewel nestled in forlorn velvet.

Did I emerge transformed? I didn't, not really. Is my perception of 1997 altered retroactively? It has not been. My personal favorite Radiohead album, 2001's stellar Amnesiac, hasn't been toppled from its perch. I would still rather revisit "Present Tense" from 2016's pretty great A Moon Shaped Pool than go for an immediate fifth, sixth, or seventh round with OK Computer. But I certainly can appreciate Radiohead's third LP as a transitional move, a stepping stone away from where they'd been before and toward a complicated, fractured immortality.

Mic has ongoing music coverage. Follow our main music hub here.