He travels the world in a 400-lb. wheelchair — and he’s helping others with disabilities do the same

More than 10 million people visit China’s Great Wall every year. In April 2014, John Morris was one of them, though he went about it a little differently from fellow tourists: He took in the striking sight of the massive and complicated architectural work sitting in his 400-pound wheelchair.

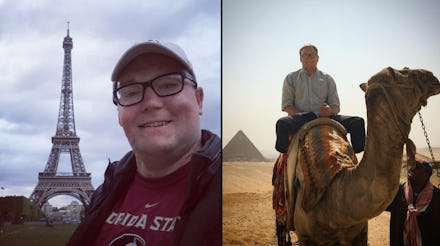

Morris is a 28-year-old triple amputee and wheelchair user, who, with one passport, one arm and no legs, has traveled to 29 countries and territories since a life-changing car accident in 2012. Morris evaluates what it’s like to travel with a disability and keeps a website with resources, tips and reflections on his own experiences to inspire and assist others with disabilities to see the world.

He didn’t plan to become an advocate for people with disabilities. Morris initially documented his travels to keep friends updated on his adventures. But it wasn’t long before he discovered people from all over were coming to his site for information.

“I didn’t understand the significance of the demand for accessible travel,” Morris, who’s now 28, said in an interview. “It wasn’t just a handful of people who were interested in this information; it was hundreds of thousands of people.”

More than 1% of people in the United States use a wheelchair. There is a hefty set of disability rights laws that affect the travel industry: The American Disabilities Act, passed in 1990, “prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life.” The ADA has put design standards in place for spaces like hotels, restaurants and movie theaters. Air travel is governed by the Air Carrier Act, which prohibits discrimination against those with disabilities in air travel — same deal. The mandates are in place, but not all businesses practice the standards.

“Pretty much every problem that I do face in traveling with a wheelchair in terms of barriers to accessibility are actually violations of existing law,” Morris said. He continued:

“These issues are not unique to me. They’re really much more common than anyone would believe. I just think that if the government would take a more active role in enforcing the right that we are already supposed to have, then more people would be encouraged to get out there and travel. As of right now, a lot of people chalk it up to being too risky.”

Stories about mistreatment of airline passengers with disabilities often make headlines, elicit outrage and sometimes move the needle, and Morris said he’s encountered plenty of discrimination himself. But these aren’t the stories he chooses to write about; he’d rather work with businesses to improve accessibility. Plus, he said, there are countless examples of businesses and cities making headway, and even though he’s in the unique position of being “late to the disability party,” he’s been able to see progress happen in real time.

“People aren’t asking for a monumental investment; what we’re asking for is the adherence to a basic set of standards that will allow people to participate in society.” — John Morris

In the summer of 2016, Morris flew across the world to Phnom Penh, Cambodia. “For someone like me using a power wheelchair, Cambodia really appeared off-limits,” he said, explaining that the transportation Cambodians rely on are hardly ideal for people using wheelchairs. At that time, however, the city was debuting the Mobilituk, the world’s first wheelchair-accessible Tuk Tuk (a three-wheeled taxi), and Morris was eager to try it. He even captured video of the experience:

“It was just sort of amazing to see the movement that is growing there about bringing accessibility to people who haven’t seen it before in a very affordable way,” Morris said. The wheelchair-accessible Tuk Tuk is not an astonishing technological achievement — it’s really just a ramp attached to the back of an existing vehicle.

But the recent development is especially significant because the country has one of the highest ratios of amputees per capita: Unexploded landmines leftover from the 1980s still litter the countryside, and unsuspecting victims are injured at an alarming rate. The Tuk Tuk signifies a movement and proves that accessibility doesn’t have to be very complicated, or very expensive. “People aren’t asking for a monumental investment; what we’re asking for is the adherence to a basic set of standards that will allow people to participate in society,” Morris said.

Advancements like the Mobilituk are part of what excites Morris most about his advocacy; “I was downright giddy,” he wrote on his blog, as he considered how many more people would be able to see the world if the technology caught on.

Beyond government mandates and tech innovations, Morris has found that it’s other people who make his experiences possible.

“I think for the disabled traveler, our safety net exists in the goodness of humanity,” he said. Morris recalled a precarious moment during his time in Beijing when, for the first time, his wheelchair battery died. Morris waited, immobile, for about 10 minutes, until he was able to find a man who spoke English. The man pushed him the five blocks back to his hotel. “It’s instances like those that have really made me believe that things always work out in the end,” he said.