‘National Geographic’ has reckoned with its racist past — now what?

It’s difficult to look at old issues of National Geographic and not cringe. The magazine published its first issue in 1888, when America began flexing its muscles as an imperial power, and eventually employed the finest photographic talent of the day to head out and bring back stories of the noble savage back to the white world.

For example: one caption on a 1916 photo of two Australian indigenous people says: “These savages rank lowest in intelligence of all human beings.”

The magazine was, in no ambiguous or uncertain terms, racist. Until this week, it had done little to come to terms with its role in telling the white world of the 20th century of its superiority.

On Monday, National Geographic editor-in-chief Susan Goldberg, both the magazine’s first female and first Jewish editor, published an editorial declaring that it was time to set the record right on the magazine’s racist history, writing that “to rise above our past, we must acknowledge it.” The magazine’s upcoming issue on race will include a series of corrective articles exploring, for example, the construction of white identity and the history of bunk racial science. In doing so, National Geographic is setting a new standard not just for themselves, but for publications that continue to advance racist causes into the 21st century.

“What we wanted to do was an issue about the topic of race, and what’s happening at this important moment in time, historically,” Goldberg said in an interview. “But I didn’t see a credible way to do that without discussing our own role.”

To have a fair investigation, Goldberg brought in an an outside auditor, John Edwin Mason, a scholar of not just African history and apartheid, but photography. Mason had already surveyed the history of race in Life, another iconic magazine that combined evocative photos with anthropological writing to chronicle American culture throughout the 20th Century. Mason grew up, like many Americans, in a household that kept stacks of National Geographic magazines as an ever-growing encyclopedic record of the world.

“For a lot of people, this magazine is a part of their childhood as a way that they saw the world, and a lot of people as children took these images in uncritically,” Mason said in an interview.

With free and unrestricted access to the National Geographic archives in Washington D.C., Mason combed over 130 years of the magazine’s history. Mason focused most of his attention on issues published during significant moments in African history, like the crowning of Ethiopian King Haile Selassie. What he found was that until the 1970s, when changes in magazine leadership finally adapted its coverage to post-civil rights America, National Geographic’s white explorers regularly portrayed Africans and African Americans in ways that reinforced ideas of racial hierarchy.

“Americans and British saw ourselves as partners in empire, and there was a belief that the white world had the right to rule the black and brown world, and at very best had a responsibility to uplift them and bring them to the light of civilization,” Mason said.

Readers of the magazine were never unwitting rubes, passively taking National Geographic’s voyeurism at face value. Stephanie Hawkins, another scholar who was once afforded access to the National Geographic archives, combed through over 500 letters to the publication from the early 20th century. For her book American Iconographic, Hawkins said in an interview that she excavated readers’ condemnations of the magazine’s imagery, and its problematic vocabulary.

“In volume XXXV [...] you use the words ‘Southern Darky,’” one reader wrote in 1919, “These are the words of the lower stratum of the white South. The word ‘Darky’ is very offensive to the refined and educated colored man. We expect better language from a first class magazine.”

Hawkins said that the New Yorker particularly served as a foil to National Geographic, and once printed a cartoon of a bare-breasted black woman at a models’ casting call with the caption, “Practically all my calls come from the National Geographic.”

National Geographic did virtually nothing to respond to these critiques until recently.

Magazines that once held gilded sovereignty over the American imagination can no longer afford to maintain their vested authority without self-awareness — not in the age of social media and increasing distrust in mainstream news. National Geographic is far from the only guilty party increasingly dragged into the greater conversation of the media’s accountability to social progress.

Throughout U.S. history, the media’s stewardship in curating and advancing racist causes isn’t limited to blatant racism. Journalists still do the work of subtly advocating for segregation, gender discrimination, foreign intervention, censorship and austerity.

“If you were to go back a few decades in the archives of any publication around for a half century or so, you’d find some fairly shocking things in the back issues,” Jim Naureckas, media watchdog and editor of Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, said in an interview.

Media’s treatment of African American leadership during the Civil Rights movement, for example, would shock the sensibilities of those who hold up figures like Martin Luther King Jr. as an icon. The upcoming 50th anniversary of King’s assassination was in fact one of the inspirations for National Geographic’s race issue. It was the Washington Post that insisted at the time that King had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people.”

Kentucky’s Lexington Herald-Leader apologized in 2004 for not having covered the Civil Rights movement at all. And it was the New York Times, the New York Daily News, and the New York Post that allowed President Trump to run full-age ads in 1989 calling for the execution of five young black men wrongfully accused of rape.

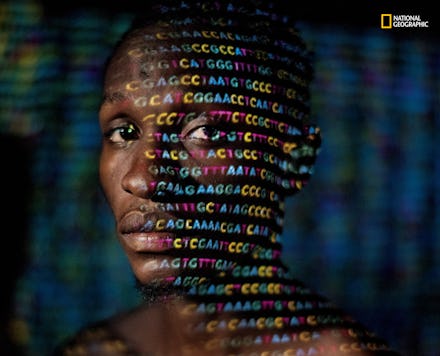

One persistent debate that National Geographic is attempting to correct the record on in its upcoming issue is race science, the bunk field of study that insists in subcategories of the human species, and argues that certain racial groups enjoy, for example, higher IQs. The New Republic has repeatedly condemned its own role in publishing a lengthy preview of Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve, a foundational text in the theory of racial IQ, in 1994.

Though scientific racism has long been debunked, the debate has yet to be settled. For every lengthy taxonomy explaining precisely how insidious and pseudo-scientific racial science is, there are a dozen op-eds condemning campus activists and anti-racists who dare to protest speakers who continue to enjoy lucrative careers as public intellectuals. Media organizations can issue public retractions and rebukes, but racist ideas will march on forward without the media’s close attention to correcting the record at every future opportunity.

“It’s simply not enough for institutions to claim they’ll no longer be racist,” Ibram Kendi, the founding director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University, said in an interview with Mic. “An institution needs to demonstrate that these ideas are not only racist, but false, and show studies that disprove those ideas, and have been disproving them consistently.”

The April race issue will be only the beginning of a year’s worth of coverage in National Geographic on race and identity, both at home in the U.S. and elsewhere. Mason, for his part hopes that to write this coverage, the magazine will employ non-white and non-American voices who can tell those stories. Only continuing accountability and reflection, measured against the actual trajectory of social change, can be the judge of whether they will have done enough.

“Those of us living now didn’t create that content, but the publications still own those histories,” Goldberg said. “But we need to own those histories, because that’s how we can remind ourselves that we have a long way to go.”