Think Ted Cruz Or Obama Are Radicals? So Were Jesus and MLK

In politics, and especially in light of the recent government shutdown, one of the most common ways that people deride and dismiss their opponents is by calling them "extremists" or "radicals." President Barack Obama does it, radio pundit Rush Limbaugh does it, even journalist Ron Fournier does it in explaining how "crazies" are ruining the Republican and Democratic parties.

But there's at least two big problems with this sort of rhetoric. First, these words are so poorly defined that it's not clear who they apply to. And second, people throwing them around rarely explain why being a radical or extremist is a bad thing.

When does a political position become "radical" or "extreme" as opposed to "mainstream"? If you're going to call someone a radical or extremist, what evidence would you use to back it up? Polling? Party affiliation? The Constitution? I'm not sure, but the burden is on whoever uses this rhetoric to prove that it's accurate. "This person is very strongly in favor of a policy I don't like" isn't enough.

The more interesting question, though — and the one that doesn't get asked as much — is whether there's actually anything wrong with being an extremist. I'm not sure there is. Civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., was called an extremist, and he responded to the accusation in his 1963 Letter from Birmingham Jail. King admits that he was initially troubled by the label, but quickly realized that some of the most admired and admirable leaders ever were extremists:

"Was not Jesus an extremist for love … Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel … And Abraham Lincoln … And Thomas Jefferson … the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice?"

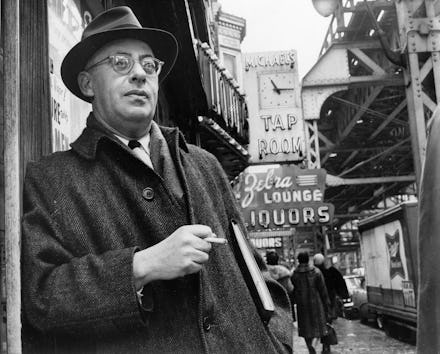

Like activist Saul Alinsky, author of Rules for Radicals, King took the label as a badge of honor.

MLK's argument — the whole letter is worth reading if you've never read it before — follows similar lines as a quote from Sen. Barry Goldwater's acceptance speech at the 1964 Republican Convention: "I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue."

The point is this: In politics, as in life more generally, we value a variety of different things that we can't always get all at once. We have to prioritize and make choices, picking one thing over the other. When we choose A over B, you could say that we're an "extremist" for A. People who would prefer B over A will say that we've gone "too far" in our commitment to A, and see us as "radical." But, of course, we could just as easily say the same about them and their commitment to B.

As King puts it, we can't avoid being extremists. The challenge is to choose and defend what kind of extremists we will be. When we dismiss somebody else's policies as being "extreme" or "radical," we're not explaining what's right about our priorities and what's wrong about theirs. We're just deriding their choice using words that imply some sort of nihilistic, militant fervor. In other words, it's name-calling.

It's very tempting to describe people who disagree with us as being impossible to get along with, as people who simply don't value any of the things that we see as good and right. But we shouldn't let frustration force us to resort to exaggeration.

Rather than writing people off as "radicals" or "extremists," we should describe (without exaggerating) what we believe is wrong with their policies, and what we think is the better way to go. That's what civil discourse is about.