9 Harmful Stereotypes We Never Realized Our Favorite Disney Movies Taught Us

We get it, Internet: You love Disney. But don't be blinded: Beneath the smiles, flowers and singing woodland creatures of the classic Disney oeuvre from our youth lies a host of stereotypes that shaped our generation. Sure, this new generation gets all the progressive glories of Frozen, but our Disney musicals were entertaining yet riddled with stereotypes. Below, you'll find nine of the most harmful Disney stereotypes we watched on repeat during our childhood. Disney seems to have learned from some of these mistakes, but looking at all these stereotypes together definitely sheds some light on the way of thinking we grew up on and what was considered normal just a decade or two ago. From outdated ideas about gender roles, to offensive representations of other cultures, let's take a look.

1. You should change who you are for a love interest. ('The Little Mermaid')

Photo via The FW

In The Little Mermaid, Ariel starts out as a brave, curious, and adventurous young mermaid. She explores the sea with her friends and saves Flounder and Prince Eric from drowning. Once she develops a crush on Eric and is briefly transformed into a human, however, she turns into a quiet, lovesick puppy, spending most of her time obsessing over the prince and staring wide-eyed in admiration at him — and he is totally into this version of Ariel. She literally becomes mute when she trades her voice to the evil sea-witch Ursula in exchange for legs (so that she can live a human life with Eric). Her demeanor changes from bold to submissive, and her former interest in human culture narrows to just seeking out a kiss. She ultimately "gets" the prince, but at the expense of having totally revised her personality and leaving her friends, family and world behind. The message here, kids: Don't be yourself if you want someone to fall in love with you.

2. Men are hopeless and need women to take care of them. ('Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs')

In Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, one of the seven dwarfs is straight up named Dopey, and each and every one of them is portrayed as a hapless dummy who can't take care of himself. Snow White saves these slovenly adults from their pigsty by dusting, sweeping, washing dishes, tidying and sprucing — tasks that the dwarfs apparently never learned from their mother (since women must teach men how to do all the things).

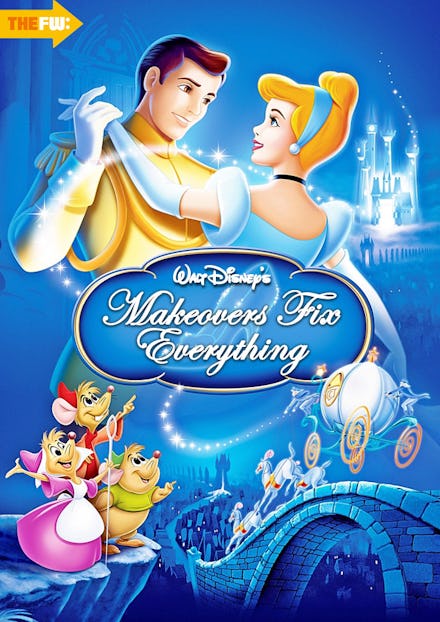

3. Outward beauty is what makes you special. ('Cinderella')

Photo via The FW

This is arguably the message of most Disney films, but it's exemplified most in Cinderella, where the basic plot of the story is that a prince sees her all dolled up, thinks she's super cute and falls in love with her on the spot. Sleeping Beauty is another big offender: Aurora and Prince Phillip instantly fall in love upon meeting, spend absolutely no time getting to know anything about each other, and then live happily ever after. Literally all Aurora does to receive "true love's kiss" is be beautiful. This sends a message that when it comes to love and affection, it's what's on the outside that counts. Attractiveness is synonymous with happiness. Equally important: Though men don't play central roles in these two examples, being handsome is always a stipulation for being a desirable prince in a Disney movie.

4. Being thin and white is what makes women beautiful and valuable. (Everything pre 'Mulan')

Photo Credit: Fanpop

Concurrent with the notion that outward beauty is most important is the message that this beauty has a specific look: thin and white. While the Disney princess list now includes a handful of non-white women — Tiana from The Princess and the Frog, notably — the "major" Disney princesses that most 20-somethings grew up with were pretty effing white (white as snow, if you will) and very thin. Megara from Hercules has the most impossibly tiny waist you will ever see.

There's nothing wrong with being white and/or skinny, but growing up, we were exposed to heroines who all looked remarkably similar. This has a host of implications: That thinness and whiteness makes you valuable, prosperous, moral and beautiful. This also implies that the opposite is true: Non-whiteness and non-thinness is unwanted, undesirable, evil and unattractive. Disney seems to (ever so slowly) be catching on and adding more variety to their characters, but there's still an incredible amount of work to be done if young women are to have relateable characters to look up to.

5. Weight determines temperament. ('Beauty and the Beast')

Photo via Blu-ray.com

Disney would have you believe that being small and waif-ish makes you gentle and kind, and that being large makes you beastly, coarse and/or prone to angry outbursts as demonstrated by characters like Beauty and the Beast's Belle and Beast. Yes, Beast is, well, a beast, but his juxtaposition with tiny Belle implies that one's literal body size affects mood, essentially teaching children that fat people are mean and angry, and skinny people are sweet and nice.

See also: Ursula.

6. Women have to be strong AND gentle. ('Pocahontas')

In most Disney films, men are not called upon to be anything but strong (sometimes additionally smart or clever, or just handsome). But in Disney films like Mulan and Pocahontas, the stories revolves around strong female leads, and there's a double standard. Women must also demonstrate kindness, thoughtfulness, gentleness and humility — femaleness, essentially — in order to be acceptable "strong female" characters.

There's obviously nothing wrong with a woman being all these things; it's very human. But it's a caveat that doesn't apply to men in most Disney movies: Women can be brave, but they must also have stereotypical lady qualities and maintain a pretty face all the while. Mulan and Pocahontas are two badass, warrior women and yet the films take pains to make sure we know they also are loving (demonstrated through relationships with men, and let's not even get started on the historical inaccuracies of the Pocahontas/John Smith thing) or understanding of the fact that their strength is shameful or atypical.

7. Arabs are erotic, barbaric and ignorant. ('Aladdin')

Photo via The FW

Aladdin would have you believe a long list of stereotypes of Arab culture. For one, Jasmine's clothing is extremely revealing compared to cultural and historic norms, and the women in the movie are all portrayed as sexy, exotic dancing sirens. (Which also buys into the racist and sexist idea that non-white women are all sexual or animalistic.)

The Middle East is shown as a brutal place full of brutal people. The original lyrics of the opening song, "Arabian Nights," actually included the lines "I come from a land/From a faraway place/Where they cut off your ear/If they don't like your face/It's barbaric, but hey, it's home." The words were changed in 1993 after being deemed racist.

The depictions of the characters are by and large ignorant and backward-thinking: The Sultan lets Jafar walk all over him and control him, thinks his daughter needs a man to take care of her and is seen playing with his toys or generally acting doofy. Other men in the movie are shown as sword-swallowers, coal-walkers, snake-charmers, crooks or swindlers; women are confined (in revealing clothes) to the home to do laundry.

Photo via Theories and Effects

8. Men are saviors. (See: all)

Men are saving women in practically every Disney movie ever made (usually with a kiss). In Tangled, Rapunzel is saved from a life of sequestered boredom by a charming bandit; Ariel is saved by Prince Eric in The Little Mermaid; Aurora is saved by Prince Phillip in Sleeping Beauty; Wendy and her brothers are saved from growing up in Peter Pan; Snow White is saved by a nameless prince ... you get the idea. In The Lion King, Simba is called on to save pretty much everyone (no pressure).

Disney is spreading a few different stereotypes with this focus: Women need men to save them; saving a woman makes you a man; and that only men are capable of protecting others from harm or danger.

9. Being masculine means being hot and buff (and white, obviously). ('Hercules')

Two of the best examples of this stereotype can be found in Hercules and Beauty and the Beast with Hercules and Gaston (there's no man in town half as manly). This representation of masculinity as an attractive man with big muscles and nice hair (who is usually white) is often paired with a foil played by a small and/or fat male character that plays comic relief — Phil, Lefou, Timon and Pumbaa and even Heimlich — implying that their size and characteristics are considerably less "masculine." These sidekicks are often given more "feminine" qualities: They offer advice to the hero, listen to his woes and are more caring or sensitive.

While Gaston doesn't woo Belle with his hairy, manly chest, it's clear he is meant to represent a man's man. Disney may not be making the judgment that these forms of masculinity seen in Gaston or Hercules are desirable, but the corporation is making a statement on what masculinity looks like, and in doing so presenting an unattainable standard and alienating a large demographic of men.