Why We Need 'Angry Feminism' Now More Than Ever

"Angry feminists." You've heard it all before. Part woman, part troll, the "angry" feminist is a beast out for blood and vulnerable manhoods. But in an age of "basic bitches" and "post-not-post-Mean-Girls," and during a time when self-described feminists want to "ban 'bossy,'" has the emotion that has denigrated feminism for so long actually been productive?

Any civil rights activist — especially for those currently at the frontlines in Ferguson, Missouri — would say "yes." Anger does not pass legislation, but it can incite social change. Protests don't automatically increase minimum wage, but they do create visibility, which leads to discussions that can shape a political landscape.

The problem for feminists, and to some extent the black community as well, is that they have been maligned as being angry since the dawn of the "second wave" in the 1960s. Anger is the reason cited for young women like Kristen Stewart and Taylor Swift, among others, originally refusing the political identity. The stereotype is also negatively applied at large to women of color — need we even delve into the media fiasco that was the New York Times' egregious, infuriating use of "angry black woman" to stereotype Shonda Rimes' contribution to television?

But the deliberate appropriation of the loaded, "feminine" emotion is changing feminist discourse for the better. From Jezebel to Jessica Valenti, feminists are saying "hell yes" to being angry. Madeleine Davies' unmitigated rant perhaps said it best — "I'm still angry, still furious," Davies wrote before launching into a list of reasons that seems to go on forever: "I am furious at the people who will inevitably tell me to calm down after reading this."

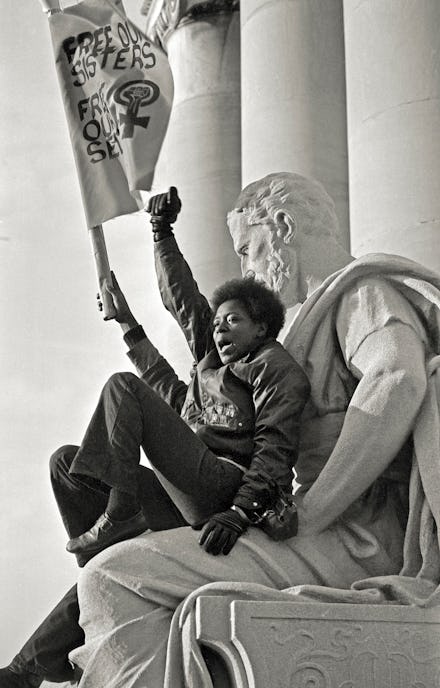

It is this deliberate, consciously crafted anger that connects this current wave of feminism with the earlier waves. The upcoming documentary She's Beautiful When She's Angry depicts the rise of the second wave in the 1960s, from the foundation of the National Organization for Women through Roe v. Wade.

Focusing on the movement's grassroots elements and individuals — like Rita Mae Brown, Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton and Kate Millett — the film shows how the battle is never over, that the struggle for gender equality and for women's control over their own bodies is never completely won. Unlike the documentary MAKERS, which aired on PBS, She's Beautiful When She's Angry will open in theaters and, more importantly, doesn't shy away from the radical elements of the women's rights movement, especially the vitriol and the anger — and the lesbianism.

In an interview with Mic, director and co-producer Mary Dore said the film's release comes at a "fortuitous" time because "while many areas of women's rights are diminishing, there's a huge number of young people who are fighting against limiting abortion laws, against rape culture, homophobia and the right wing's efforts to make voting difficult for people of color and older citizens."

It couldn't come at a better time. As the nation reels from a series of what many see as racial injustices, it's worth noting how the women's rights movement has historically been connected to other civil rights movements.

"I always wanted to focus on the early years of the women's liberation movement," Dore said, "since that was both crucial in terms of showing the political roots (no, it didn't sprout by magic) in civil rights and anti-war movements, as well as showing how movements develop."

Dore said making the film made her realize "how misinformed many people were" about feminism, and that she was moved by the bravery of these pioneering women, many of whom were women of color and/or queer.

"A small group of people working together can make a huge impact," said Dore, who believes anger is essential to political and social change, which is why she incorporated the overdetermined term in the film's title, one she borrowed directly from an early newsreel documentary.

"Anger is necessary to make social change," she said. "If you think everything is just great, why change it?... It works on many levels, as satire, 'You're so cute when you're mad' and as a provocation, 'What's the worst thing a woman can be?' Angry! Or an angry black woman, the worst thing on Earth!"

Instead of shunning anger as a misogynistic stereotype, feminists and women in general are well advised to see its political viability and power to create change. It is an emotion weaving together women's history — and one we should not be afraid to appropriate for our empowerment.