One Troubling Chart Reveals the Harsh Truth About Inequality In America

It's one of our country's founding myths: Everyone is born equal.

But a new study from the Brookings Institution suggests that our celebrated equality is wiped out by the time we begin to walk and talk. An overwhelming majority of Americans, no matter how smart they are or how hard they work, will reach the age of 40 in the same economic class they were born.

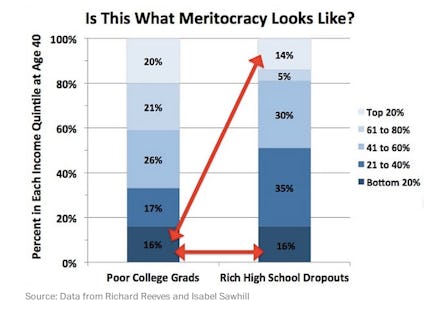

In the graph below from the Washington Post, we see that that "Poor College Grads" and "Rich High School Dropouts" are likely to end up earning the same amount as they enter middle age:

It's getting worse: Richard Reeves, whose work with budget expert Isabel Sawhill formed the basis for the chart, writes in his "Saving Horatio Alger: Equality, Opportunity and the American Dream" that "there are forces at work in America now — forces related not just to income and wealth but also to family structure and education — that put the country at risk of creating an ossified, self-perpetuating class structure, with disastrous implications for opportunity and, by extension, for the very idea of America."

In this YouTube clip, Reeves illustrates just how unlikely it is for someone born at the bottom to end up anywhere near the top:

Don't let the cute Lego people fool you. The message is troubling, and backed by a mountain of new and increasingly urgent statistics.

A January study from the National Bureau of Economic Research showed that economic mobility in the U.S. has remained stagnant for the better part of 30 years. Children born to "parents in the bottom fifth of the income distribution" in 1971 had an 8.4% chance of reaching the top one-fifth themselves. Fast forward to 1986 and that number had moved less than a point, to 9%.

Education remains the best vehicle out of rough economic terrain. But even as the number of people with college or postgraduate diplomas hits an all-time high, students' likelihood of pursuing or having the opportunity to pursue higher education is still deeply rooted in their parents' income.

The NBER study shows only a slight movement between the class of 2006 and graduates a decade younger:

Children born to the highest-income families in 1984 were 74.5 percentage points more likely to attend college than those from the lowest-income families. The corresponding gap for children born in 1993 is 69.2 percentage points, suggesting that if anything intergenerational mobility may have increased slightly in recent cohorts.

Most troubling is the indication that the effects of economic inequality are felt as early as preschool and kindergarten. In a June memo released by the Hamilton Project, economists found that "despite similar starting points, by age 4, children in the highest income quintile score, on average, in the 69th percentile on tests ... while the children in the lowest income quintile score in the 34th and 32nd percentile."

How is this possible? The 2011 book Whither Opportunity? points to a significant built-in advantage for wealthier children: time with their parents. In a chapter called "Parenting, Time Use and Disparities in Academic Outcomes," Meredith Phillip presents evidence that by age 6, children raised in wealthier households will, on average, have had the benefit of 1,300 more hours of "enrichment activities such as music lessons, travel and summer camp."

Deeply rooted and politically intractable as these issues might be — the potential solutions don't fall neatly into either major party's political platforms — there has been some success in expanding access to early education. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio has finally launched a "universal pre-K" program that sent, per the New York Times, "a fresh crop of 4-year-olds, more than 50,000, embarking on the first day of free, full-day, citywide, city-run prekindergarten" this September.

What can we do about it? Even progress at a younger age supposes that those students will eventually have the opportunity to reap the benefits of a stronger educational underpinning. An increasing amount of research, a fraction of it cited here, show that this is very much in doubt.

Without better access to more affordable college loans and a higher education system that makes an active effort to recruit from outside its usually white, privileged pool of applicants, the fact remains: In America, there is nothing more indicative of where you end up than where you start.