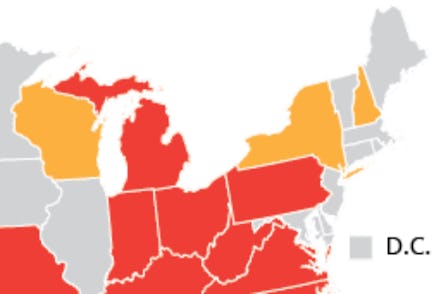

This Map Shows All the States Where You Can Still Be Fired for Being Gay in 2014

Tim Cook's public announcement last week that he's gay was a celebratory moment that marked the first time a Fortune 500 company was being led by an openly gay CEO.

"I've been open with many people about my sexual orientation," Cook said in a statement. "Plenty of colleagues at Apple know I'm gay, and it doesn't seem to make a difference in the way they treat me. Of course, I've had the good fortune to work at a company that loves creativity and innovation and knows it can only flourish when you embrace people's differences."

But Cook also noted not everyone is able to come out the way he did, saying that "there are laws on the books in a majority of states that allow employers to fire people based solely on their sexual orientation," as well as countless forms of discrimination against the LGBT community that are still lawful in America.

While not surprising for LGBT advocates, this may come as a shock to most Americans — according to a 2013 HuffPost/YouGov poll, 69% "think that firing people for being gay is illegal."

Indeed, in 29 states it is legal to fire someone based on their sexual orientation. Barring protections provided by Title IX, 32 states still lack protection against gender discrimination.

According to an American Progress report using 2010 census data, this means that over half of the labor force is susceptible to workplace discrimination:

While President Barack Obama's executive order this year protects federal workers from LGBT discrimination, there is still no federal law that prevents the discrimination nationwide. The Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) has been sitting in Congress for two decades with no hope of it becoming law anytime soon; the most recent incarnation passed in the Senate last fall and is awaiting a vote in the House.

This means that coming out at work for many people isn't even an option. And, as Dorie Clark noted on MSNBC, there is a psychological toll of staying in the closet or remaining "covered" — that is, kind of out, but not really.

We need to keep in mind, as Darnell L. Moore points out in the above segment, that Cook coming out happened in a privilege space — today, 91% of Fortune 500 companies have LGBT protections. Furthermore, Moore notes that "folks outside the demographic" that Cook resides in — "white, cisgender, gender-conforming, gay male and wealthy" — live in bodies that are already oppressed; they are bodies for which coming out is an even more complicated process. Not to mention that those bodies — queer bodies — are poorer and comparably have higher rates of unemployment and homelessness than others.

Clark further notes that in America today more states have same-sex marriage than workplace anti-discrimination protections. The hypothetical situation of a gay person telling their workplace that they got married only to hear the reply, "Congratulations, you're fired," might seem far-fetched, the possibility of it happening is real.

One unintended effect of Cook coming out is that it brings attention back to the fact that coming out is not an option for everyone. Only federal law can remedy this societal problem.