California Passed the Most Important Ballot Measure That No One Is Talking About

Major victories for marijuana legalization and minimum wage drew enormous fanfare on Election Day, but a ballot measure quietly passed in California could mean even more for the future of the country.

Proposition 47 downgrades penalties for a number of nonviolent drug and property crimes from a felony to a misdemeanor. It passed with support from 58% of voters.

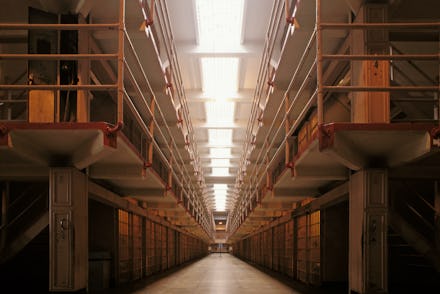

It may not sound revolutionary to lessen the intensity of punishment for a set of crimes, but in a state whose criminal justice policies have become a dark icon of the United States' unparalleled zeal for incarceration, the measure is a crucial shaft of light.

More prisons, more problems: California's criminal justice system is one of the harshest in the country. The state is most notorious for its 1994 "Three Strikes and You're Out" law, which imposed a life sentence for almost any crime, no matter how small, if the defendant had two prior convictions deemed serious or violent by the California Penal Code. The state is under a Supreme Court order to cut down its massive prison population, which suffers from the kind of overcrowding that led then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to ship inmates off to private prisons in Mississippi and prompted a federal judge to estimate that a prisoner died every week purely due to medical neglect.

Experts see the new proposition as a necessary step toward correcting California's mass incarceration debacle. "It would officially end California's tough-on-crime era," Thad Kousser, a professor of political science at the University of California at San Diego, told the Washington Post.

It's not the state's first attempt to mitigate the extremity of the three-strikes law. In 2012, a measure was passed that prevents a life sentence when the third conviction is for a minor crime.

Proposition 47 is the next step in dismantling the three-strikes regime. People convicted of the offenses that have been reclassified under Proposition 47 will now face shorter stays in jail or community supervision. According to the Los Angeles Times, the annual number of felony convictions in California should be reduced by 20%.

As important as these reforms are, if California wants to seriously reduce its prison population, it must reckon with how it views violent and serious crimes, of which a vast majority of its prisoners have been convicted. The Urban Institute has argued that California is going to have to become far more ambitious in reducing its sentencing for violent and serious crime, even if only to maintain the reductions brought about by recent reform.

Where next? For critics of America's criminal justice system, the hope is that reform in California will help carve out reform across the nation. Federal reform is an urgent matter. More than 2.4 million Americans are behind bars today — more than the combined population of 15 states or the U.S. armed forces. And that problem is racialized: The United States imprisons a larger percentage of its black population than South Africa did at the height of apartheid.

For serious changes to take place, we need to rethink why we put people in prison in the first place. Is it to rehabilitate them? Or is it, as recidivism rates and institutionalized discrimination in employment, housing, education and voting rights suggest, to debilitate them? People are starting to catch on.