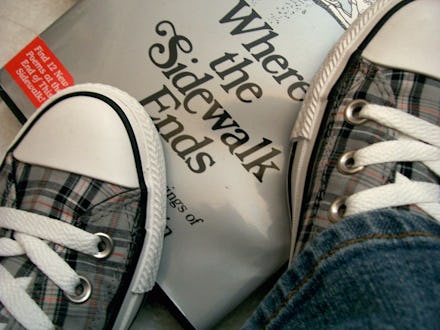

'Where the Sidewalk Ends' Just Turned 40 — and Matters Now More Than Ever

Where the Sidewalk Ends. The title alone is enough to take us back to our elementary school days, sitting on itchy classroom carpets, rapturously listening to our teacher read aloud some of the most beloved poetry ever written. Our imaginations fluttered with the fantastical creatures from the world past the end of the sidewalk. Few hear the magical words "There is a place where the sidewalk ends..." without being overcome by a warm wave of nostalgia.

On Friday, the seminal collection of children's poetry turns 40. It has lived a lifetime, having inspired generations to "follow where the arrows go." But its themes and lessons about imagination matter more now to adults than ever before.

In Silverstein's book, he tells the magical story of leaving the city to enter an astonishing world full of peppermint winds and moon-birds. At the very beginning, the wordsmith invites readers into the place beyond the sidewalk:

"If you are a dreamer, a wisher, a liar, / A hope-er, a pray-er, a magic bean buyer, / If you're a pretender, come sit by my fire, / For we have some flax-golden tales to spin. / Come in! Come in!"

As we grow older, we lose the spark of childhood: the extreme curiosity for things unknown, the desire to explore less-taken paths, the hope for a world that never loses its mystery. As adults, we're bogged down by bills and 9-to-5 workdays and the compulsion to prove ourselves to our parents — obligations that render us incapable of seeking out more than a little red wine and pizza. With Silverstein's words, we're reminded of the dreams and fantasies that we once had. His writing can transport us to a place where the answer to every yearning isn't "no" or "later" or "when I've figured my life out."

"Donald heard a mermaid sing, / Susy spied an elf, / But all the magic I have known / I've had to make myself."

The fantastic place that Silverstein creates isn't new by any means; using other dimensions or worlds as metaphors is a common device in literature. But Silverstein transports readers there through poetry, a medium often ignored in children's books as "not commercial," or ignored by children themselves as "too boring." He shows that prose isn't the only vehicle to to imaginary worlds, and his use of illustrations add another layer of depth and warmth to the stories he tells.

The bulk of Silverstein's work transcends time. Where the Sidewalk Ends was written in 1974, The Giving Tree in 1964. Both are staples on Amazon's top 100 bestsellers in children's books, holding their own against titles like the Harry Potter series and The Hunger Games. They continue to flourish because Silverstein's pieces hit on innate parts of childhood: imagination and gratitude.

Grown-ups can never truly return to the innocence and imagination of childhood, but we can recapture some of that lost zest for life. Maybe that's why television shows like Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead are so successful — they tap into the fantasies and fiction that adults once so easily accessed. It's what makes rereading Where the Sidewalk Ends feel like coming home.

Some may want to grow up fast, while others try to hold onto their childhood as long as possible. Whatever camp you fall into, Where the Sidewalk Ends reminds us to never stop dreaming of peppermint winds and moon-birds.

"There is a place where the sidewalk ends