11 Black American Icons You Won't Learn About On MLK Jr. Day — But Should

One day, just like one month, isn't nearly enough.

If the Black Lives Matter movement has taught us anything these past couple of months, it's that every black life matters. But more than that, it's proven that a single voice can never truly be representative of an entire moment. One federal holiday and one month celebrating black heritage, culture and activism is pithy at best, insulting at worst.

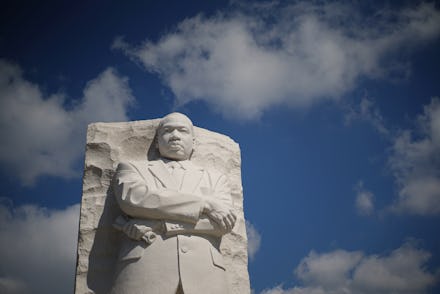

Martin Luther King Jr. is a symbol of civil rights for good reason. His passion for activism is and was an inspiration to countless others. But he was not alone in these endeavors. Americans like heroes, even if that means we have to rewrite history a little in order to simplify it. But if the past has taught us anything, it's that you cannot truly understand history in digestible soundbites.

Therefore, in honor of a holiday that has come to represent the spirit of the civil rights movement, we've compiled a list of the heroes you probably won't hear about on Monday. These are the people who marched in the streets of Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, side by side with King, who delivered inspiring speeches about civil rights and ending racial oppression, icons who, in their distinct way, expanded King's vision of "the revolution for human rights" to include women and queer people.

Harriet Tubman (1822-1913)

Tubman escaped from slavery when she was 29 years old and spent the rest of her life dedicated to helping others escape too using abolitionist friends and the Underground Railroad to facilitate slaves' journey to freedom. During the Civil War she was even a spy for the North. After the war, and later in life, she focused her advocacy on women's suffrage.

Booker T. Washington (1865-1915)

Born into slavery, Washington describes in fascinating detail what it felt like to be a slave during emancipation at the end of the Civil War in his autobiography: "The wild rejoicing ... lasted but for a brief period, for I noticed that by the time they returned to their cabins there was a change in their feelings. The great responsibility of being free, of having charge of themselves, of having to think and plan for themselves and their children, seemed to take possession of them."

Washington believed in education to help people transcend their social station in life. A revered orator, Washington extolled the idea that education not only led to freedom of station but freedom of mind, which was, he believed, the black person's greatest form of liberty in a profoundly racist world.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931)

If Wells-Barnett were alive today, she'd probably be a writer at Mic. She was a perspicacious journalist who documented the rise of lynchings, post-Emancipation, in the late 19th century, as a form of white panic about freed slaves. Born into slavery, she fought racial prejudices not only in print but in her own life as well. In a notorious 1884 incident outside of Memphis, Tennessee, she refused to give up her seat on a railroad train to a white passenger. She was then dragged off the train, kicking and screaming. Wells hired a black attorney and sued the railroad company — and won. She was the original Rosa Parks and journalistic firebrand.

W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963)

"Second sight." It is one of many great concepts give to the world by sociologist DuBois, most notably in his seminal collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, published in 1903. The text was a cry for the world to see the humanity of black people. It also delved into the psychology of the black man, who developed a "second sight," or ability to see the social structures of racism in America and how it kept him down. DuBois was the first African-American to earn a doctorate from Harvard, and was a co-founder of the NAACP.

Malcolm X (1925-1965)

Malcolm X is often, and generally incorrectly, posited as the anti-King, largely because of misunderstanding and fear surrounding his adopted Muslim faith. Born Malcolm Little and later known as the minister El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, his name has lived on as a symbol for radical black justice against racist oppression.

Knowing that white America didn't want racial equality, he preached for separation, not segregation, early in his career: "Separation is when you have your own. You control your own economy; you control your own politics; you control your own society; you control your own everything. You have yours and you control yours; we have ours and we control ours." Later in life during a pilgrimage to Mecca in the 1960s he witnessed Jews and Muslims and Christians all living together in harmony, which convinced him, as he narrated to Alex Haley in his autobiography, that social and racial integration was possible in America.

Bayard Rustin (1912-1987)

Rustin was an openly gay black man and fierce proponent of peace and equal rights. He was an early leader of the civil rights movement, joining the Freedom Riders in the 1940s, and he is considered one of the movement's leading strategists behind the civil rights legislative and judicial victories of the early 1960s. He was known as the civil rights' top organizer, organizing such events as the March on Washington and the New York City School Boycott. A declared pacifist, his friendship with King was nevertheless severely strained because of his homosexuality, for which he was arrested in 1953.

In the 1980s he championed gay rights, and in a speech, asserted that "blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change. Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new 'n*****' are gays. ... It is in this sense that gay people are the new barometer for social change."

James Baldwin (1924-1987)

Go Tell It On the Mountain, the title of Baldwin's first pseudo-autobiography, captures how quintessential he was to civil rights throughout the 20th century. Notes on a Native Son, Giovanni's Room and The Fire Next Time are just some of his writings that have had deep and lasting impact on black culture, for how they discuss how black men intimately and platonically have relationships with one another.

He advocated for equality on behalf of both the black and gay communities. Baldwin, a gay black man like Rustin, was arguably the first black public intellectual, appearing on television programs and even taking on and smacking down panels of racist white men. His debates are legendary — and he debated them all, from Malcolm X to crazy white racist William Buckley.

Audre Lorde (1934-1992)

Baldwin's friend and lesbian poet, writer and professor Lorde was a comrade fighting for the civil rights of people of color — women and queer women specifically — using the power of her pen. Lorde preached the power of "the erotic," or what she describes as an "unexpressed," feminine power. She was as great a public intellectual as Baldwin, albeit less celebrated, probably because she was a woman. And she knew that. When, in a fantastic debate in Essence magazine in which Baldwin exclaimed "DuBois believed in the American dream. So did Martin. So did Malcolm. So do I. So do you," she was quick to clear a few things up about the role of gender in the fight for equality and women's place in the world:

"I don't, honey. I'm sorry, I just can't let that go past. Deep, deep, deep down I know that dream was never mine. And I wept and I cried and I fought and I stormed, but I just knew it. I was Black. I was female. And I was out – out – by any construct wherever the power lay. So if I had to claw myself insane, if I lived I was going to have to do it alone. Nobody was dreaming about me. Nobody was even studying me except as something to wipe out."

Maya Angelou (1928-2014)

Writer, poet and speaker of divine justice, Angelou was not only Oprah's prophet but the world's. Born Marguerite Annie Johnson, Angelou, who passed away last year, published multiple autobiographies, beginning with the beloved I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings in 1969. While deeply personal, these autobiographies were channels for understanding the condition of black women in America throughout the 20th century. They were, therefore, examples of how art works as catharsis, as her writing spoke to black women not only in America but across the world. After she read her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993, she became an international icon, appealing "cuts across racial, economic and educational boundaries."

Alice Walker (1944-)

Author of the critically acclaimed and Pulitzer Prize-winning bookThe Color Purple, Walker is an activist whose literature speaks volumes about the intersection of race, class, and sexuality in America, specifically in the South in the mid-20th century. (She herself identifies as sexually "curious," having celesbian-like relationships with musician Tracy Chapman, among others.) In the last couple of decades, Walker has directed her activism to fight for the rights of Palestinians, even taking part in the Gaza flotilla in 2011 in an effect to call attention to the Israel's "apartheid state."

Angela Davis (1944-)

With a Ph.D. in philosophy, Davis is a professor who ended up teaching the world. Put on the FBI's "Most Wanted" list and jailed in 1970, her redemption in her 1972 court victory symbolized that maybe justice could be served in America. Davis knew that some in white America found her dangerous as a black woman and as an avowed Communist — and this was even before she came out as a lesbian in 1997.

As she wrote in the 1974 Angela Davis: An Autobiography, "The one extraordinary event of my life had nothing to do with me as an individual — with a little twist of history, another sister or brother could have easily become the political prisoner whom millions of people from throughout the world rescued from persecution and death." Davis has become a global icon fighting for the end of political oppression and for changing the current criminal justice system in America.