The Supreme Court Has Taken on Lethal Injections

One week after the Supreme Court allowed Oklahoma to proceed with an execution by lethal injection, the court announced on Friday that it will review the state's so-called "cocktail."

Following the botched execution of Clayton Lockett in 2014, where the injection of an experimental cocktail of drugs caused him to writhe in pain for 43 minutes before dying of a heart attack, Gov. Mary Fallin ordered a review of the state's execution protocol. Executions were postponed until the state completed revisions.

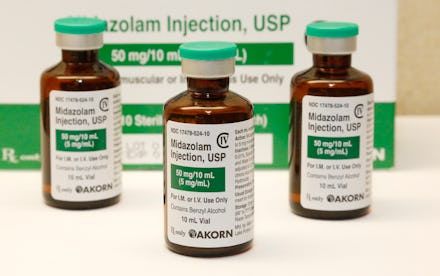

The new protocol, which went into effect in September 2014, is similar to its precedent: first, a sedative to render the inmate unconscious; second, a paralytic drug; third, a drug that stops the inmate's heart. The major change is one that dictates the administration of a much higher dose of midazolam, a sedative, in the first step. During Lockett's botched execution, 100 milligrams of the sedative were injected; Oklahoma now mandates the injection of 500 milligrams.

But inmates are protesting. After Lockett's death, several inmates on death row challenged the state's intention to use midazolam at all. "The drug protocol used in Oklahoma is not capable of producing a humane execution, even if it is administered properly," said Dale Baich, one of the attorneys representing Oklahoma's death row prisoners, in a failed appeal to the Supreme Court to stop last week's execution of Charles Warner.

Warner, who was one of the inmates protesting the implementation of the new protocol, was executed last week for the rape and murder of an 11-month-old girl over the protestations of the Court's four more liberal justices, who voiced Eighth Amendment concerns in their dissent. Justice Sonia Sotomayor cited testimony stating that the application of the second drug in the Oklahoma cocktail might render midazolam ineffective, but that it would be impossible to know whether or not the inmate was conscious: "Petitioners have committed horrific crimes and should be punished. But the Eighth Amendment guarantees that no one should be subjected to an execution that causes searing, unnecessary pain before death."

The use of the midazolam cocktail is largely the result of drug manufacturers, fearing political fallout, refusing to supply prisons with compounds traditionally used in capital punishment cases. As a result, executioners have either forgone tested cocktails (in favor of less reliable "one-drug" doses) or pushed prisons to employ "compounding pharmacies" (or lightly regulated labs) that create to-order drugs. Compounding pharmacies are subject to less oversight and are largely considered less reliable, as are the drugs they produce.

It's the biggest challenge to the death penalty since 2008. In the case Baze v. Rees, the Supreme Court rejected 7-2 a challenge to lethal injections. "Simply because an execution method may result in pain, either by accident or as an inescapable consequence of death, does not establish the sort of 'objectively intolerable risk of harm' that qualifies as cruel and unusual," wrote Chief Justice John Roberts.

However, that decision was fragmented: A majority of the court's members couldn't agree on the proper standard with which to judge methods of execution. Justice Clarence Thomas predicted that the divided decision was "sure to engender more litigation."

"I assumed that our decision would bring the debate about lethal injection as a method of execution to a close," wrote Justice John Paul Stevens, who also wrote in his dissent that his tenure on the Supreme Court has persuaded him that capital punishment is unconstitutional. "It now seems clear that it will not."

h/t Washington Post