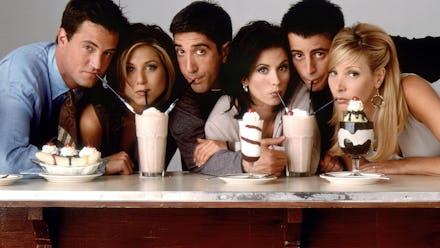

'Friends' Wasn't Just Great TV — It Was a Blueprint for Modern Relationships

The release of Friends on Netflix Instant last month prompted a critical re-evaluation of the show, despite the fact that reruns were already showing twice a day on TBS. That's because binge-watching allows us to pick out themes that are otherwise hard to spot in the segmented blocks on cable. Ruth Graham started the conversation with a Slate article on the show's homophobia, pointing out the abundance of gay jokes and the condescending attitude of Chandler Bing toward his transgender parent. The evidence to support her theory is ample (check out the nearly hour-long "Homophobic Friends" supercut), although opponents have made a strong case, as well. Readers of Andrew Sullivan's The Dish chimed in to defend the show, pointing out Chandler's unabashedly loving friendship with Joey, as well as the fact that one of Friends' creators, David Crane, is an out-and-proud gay man.

No television series is a monolith: At best, every work of art can be seen as a snapshot of its time. Friends cycled through dozens of individual writers who shaped its values over the course of 10 seasons. But looking at the beloved show in 2015, what stands out are the values represented at the show's core, which are perfectly encapsulated in the show's name. Friends is about the idea that friendship between a man and a woman can be just as rewarding as a romantic relationship, a possibility rooted in the equality of the sexes. Believe it or not, this was a pretty revolutionary idea at the time. And more than 20 years after its premiere, Friends represents one of the best portrayals of the messy, complicated, beautiful reality of modern relationships between men and women.

Most of the popular sitcoms of the 1980s revolved around families (The Cosby Show, Roseanne, Family Ties). The rest relied on "will they or won't they" romances (Cheers, Moonlighting, Who's the Boss). Some wisely revolved around both (The Wonder Years). But both types of shows are problematic because they reinforce the notion that romantic love and the pursuit of a traditional family are paramount. And it perpetuates a conservative view of gender relations that paints women only as objects of desire or homemakers. These shows reflected the politics of the era, when Ronald Reagan was advancing what many liberals considered to be an anti-women agenda: opposing the Equal Rights Amendment, supporting abortion bans and reducing the size of government agencies like the Equal Opportunity Commission.

By emphasizing platonic instead of romantic relationships (at least for the first few seasons), Friends offered a new, more progressive snapshot of social life. And the series came at a time when American audiences were ready: Beloved cinematic rom-coms like 1989's When Harry Met Sally and 1992's Singles captured the messy truth of modern friendships, in which men and women emphasized friendship and put romance on the back burner. Even Seinfeld, which debuted in 1989 and was seen by many as a precursor to Friends, refused to hook Elaine up with any of its male leads.

By emphasizing platonic instead of romantic relationships (at least for the first few seasons), 'Friends' offered a new, more progressive snapshot of social life.

Here's why this matters: Depicting women as friends of men is akin to depicting them as equals, and it's a significant social shift from when they were simply prizes to be won on a male's journey to self-actualization. Consider an anecdote from the shooting of the Friends pilot: In the original script, Monica was supposed to be dumped by a guy after sleeping with him on the first date, but the network executives worried that the audiences would not be able to relate to such behavior. They handed out survey cards to a test audience, asking if they considered Monica "A) a whore, B) a slut, C) a tramp or D) your dream date." The audience chose the last option, which revealed a distinct generational shift between TV viewers and the network executives who had been calling the shots, and it paved the way for the show's feminist victories.

Of course, Friends had more to offer than sex-positivity. Women who are not love interests are free to have richer, more well-rounded personalities. They can even have careers. The lead female characters in Friends, Seinfeld and Singles, for example, all have jobs that are important to them. With Friends, that dynamic is particularly central. Protagonist Rachel's journey to self-actualization involves cutting her financial ties to her father and fiancé in order to strike out on her own to build a life and career.

To add to that balance onscreen, the men of Friends were also designed to be vulnerable and emotional. Ross and Chandler were geeks who were generally depicted as lucky to be with their beautiful girlfriends (although Graham sees Chandler's emasculation as the potential source of a troubling misogyny). Joey, the alpha male of the group, became more vulnerable as the show progressed. He exposed his vulnerability every time he had a bad audition, and he ultimately shed his womanizing ways when he fell for Rachel in the show's final seasons.

The focus on friendship also allows the creators of film and television to think outside of the box and address the rise of alternative families. Phoebe becomes a surrogate mother for her brother and his wife, while Monica and Chandler go through an adoption process. Ross also learns to accept his ex-wife's marriage to a woman (which, because it was introduced in the pilot, is in some ways just as integral to the show's values as Rachel's journey). In a basic way, Friends and its precursors frame friendship as a replacement for the traditional family (as did the very progressive Golden Girls), but they also allowed for the possibility that getting married and having children is not for everyone.

There is a caveat: Friends – like Singles and When Harry Met Sally — ultimately ended with its lead characters falling in love. But that should be considered a comment more on the limits of progressiveness in pop culture (which, by definition, ultimately seeks to reaffirm the status quo) than an indictment of the works themselves. Seinfeld got around this problem by making its characters so unsympathetic that we didn't really care if they got a happy ending. Friends, on the other hand, was unapologetically sentimental, and that heart worked in its favor; it is often said that one of the reasons for its success is that viewers of any stripe could find a character to root for. Its depiction of modern women, so rare just a decade earlier, as well as vulnerable men, made all of that possible.

Friends, on the other hand, was unapologetically sentimental, and that heart worked in its favor.

Given the abundance of sitcoms anchored by strong, well-rounded female characters today – The Mindy Project, Jane the Virgin, New Girl – we should celebrate the shows that paved the way for them. Friends may have occasionally resorted to a cheap homophobic joke in order to draw in viewers that were generally far less socially progressive, but pop art of the past always comes with a few antiquated elements that makes us cringe. And that's how we know that progress has been made.