Scientists Want to Unlock the Secrets of Distraction — and Use Them to Your Advantage

Distraction is a double-edge sword. Our mind's propensity to wander is great when we need a diversion: It keeps us occupied and sane during meetings and helps us cope with trauma while we mentally regroup. But distraction can also ruin our lives: It keeps us from finishing those pressing assignments at work or in school or from staying focused while we're doing important things like, say, cooking and driving.

Scientists are closer than ever to figuring out how the human mind becomes distracted and how we can use it to our benefit, according to research published in the Journal of Neuroscience. That's not just a good thing in terms of helping you focus on things that require your attention — researchers think they can harness the evils of distraction for good. In fact, It might be the key to helping us deal with physical or even emotional pain.

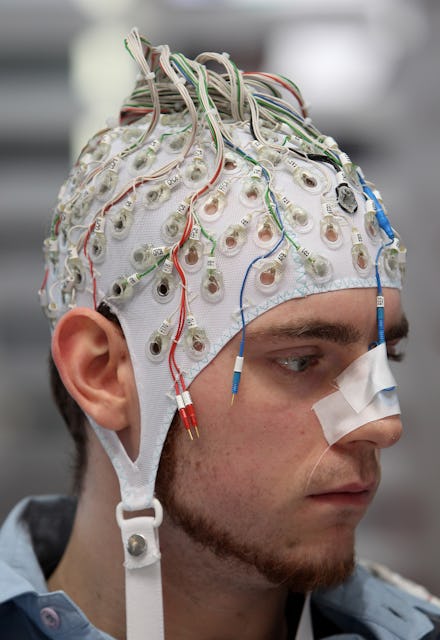

How scientists are harnessing the secrets of distraction: Right now, neuroscientists know that the brain amplifies responses to the things a person wants to focus on and weakens the nerves to the stimuli that person wants to ignore. Researchers at Brown University want to tap into our brain's power grid and figure out exactly how brain cells communicate to keep the average person from being distracted all day.

Think of this science like stage lights at the theater: A single spotlight will direct attention to one subject even while dimmer overhead lights illuminate other things and people on the stage. And even though the audience — you, in this instance — can see everything, you are focused on what's beneath the spotlight. In the same way, the brain funnels impulses toward the region that will help you to maintain focus.

Researchers suspect that by mapping the brain's mechanisms for dealing with distraction, they might be eventually able to use this information to teach us how to distract ourselves from other things like, say, excruciating physical pain.

"It's really more about making our attention more effective or efficient," Matthew Sacchet, a graduate student in Stanford University's Neurosciences Program who co-authored the study, told Mic.

The latest research is remarkable: For their study, the researchers recorded brain activity from 12 volunteers who had to pay attention to a tap on either their left middle finger or their left big toe. If instructed to pay attention to a tap on the finger, they had to ignore any taps to the toe and vice versa. The basic idea was to see how regions of the brain controlling sensory information from say, the finger, might be responding to ignoring the same kind of feedback in another region (the big toe).

The team found that in the brief second after a volunteer was told to focus their attention on either the finger or the toe, there was a distinct pattern of brain activity that indicated the brain was preparing to either ignore or take note.

"Our findings are generalizable to a wide range of behavior in our everyday lives, particularly in an increasingly distracting world," Stephanie Jones, an assistant professor at Brown who led the study, told Mic.

This seems like an isolated example, but the brain gets put to the test in this way every day beyond mere physical distractions. Just consider visual distractions. As part of another recent study on distraction led by John Gaspar for Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia, researchers tried to spot a single yellow circle among a bunch of green ones without paying attention to the flashy red ones. Gaspar's team found that the mind constantly suppresses potentially distracting visual objects when subjects were attempting to fixate on a particular task.

The consequences: The researchers aren't ready to embark on any pain-inducing experiments just yet, and their work is preliminary. They still have a long way to go before they unravel all the science behind the brain waves they studied in their scans.

"Beyond pain, these brain waves may be involved in the filtering of distracting or negative thoughts or ruminations and therefore relevant to studies of depression," Jones said.

Neuroscientists are convinced that harnessing the brain's mechanisms for coping with distraction is the best way to deal with physical pain. Gaspar told Mic that the idea we might somehow be able turn our senses to pain down is a "cool possibility" but "premature." Pain, he said, is handled much differently from other sensations in the brain.

"Pain actually carries not only very salient information but also very relevant information that the body might not have an easy time suppressing in this same attentional fashion," he said.

But Sacchet points out that the research is about more than just "distraction" — it's about attention control. He said identifying ways to harness this power benefits more than just individuals with psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, it would probably help everyone.

"Improved attention can help people be more effective in general, whether it's in fast-paced traffic, engaging with friends or understanding one's own mind," Sacchet told Mic. "Attention is a fundamental aspect of engaging with the world, and therefore the implications of better attention are really quite broad."