Jeb Bush Says He's Not Like His Brother. Don't Believe Him

For former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, the family legacy is both a blessing and a curse. But mostly a blessing: His tribal connections allow him to tap into an existing network of fundraisers who have already shelled out millions of dollars to support his likely campaign for president. If he had any other last name, no one, for any discernible reason, would be discussing him as the frontrunner for the Republican nomination in 2016.

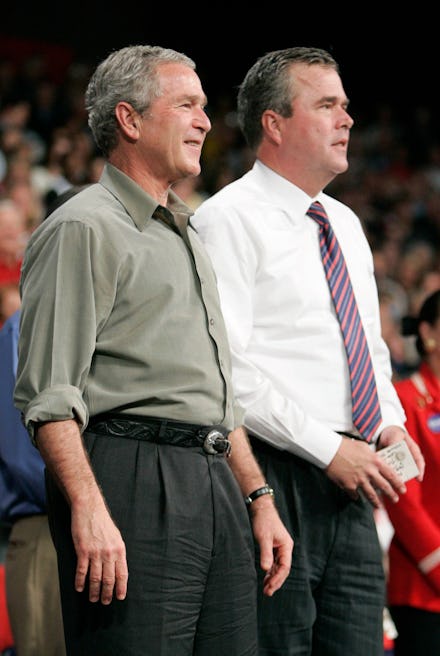

But politics being what it is, the brother of one former president and son of another is confronted with a challenge: how to leverage his significant built-in power base while keeping some sort of "distance" from those close family members. In particular, Bush will have to navigate his relationship with George W., who didn't leave the White House on the best terms with American voters.

Which brings us to Tuesday in Chicago. Bush, in the course of a meandering speech on foreign policy, made this headline-grabbing declaration: "I love my brother, I love my dad. And I admire their service to the nation and the difficult decisions that they had to make. But I'm my own man, and my views are shaped by my own thinking and my own experiences." (Only a politician could smilingly cast his love of family in opposition to a basic sense of individual propriety.)

Bush, though, had not been seized up by an untimely surge of household pride. This was a plain pitch to voters: The 62-year-old former governor is a proud Bush, sure, but only up to a point.

The stagecraft in Chicago also managed to obscure a considerably more interesting development in the Bush campaign. Just hours before the speech, Bush's top aides rolled out a cadre of former U.S. foreign policy wonks and wizards who would be advising him through this long process. At least 19 of them have deep ties to the earlier Bush presidencies. And they represent 19 reasons to question the notion that Bush's "own thinking" will be guided by his "own experiences."

The nightmare team: Republican establishmentarians will be quick to note that the bench of qualified advisers without ties to George H.W. and George W. is bound to be small, given it's been more than 25 years since a Republican president not named Bush occupied the White House. But this is nonsense. There are thousands of experienced and thoughtful potential advisers on offer who served in neither Bush administration. These, simply stated, are Bush's favorites.

Among them: Paul Wolfowitz, a neoconservative former deputy secretary of defense under Donald Rumsfeld who played a leading role in sculpting the case for war with Iraq in the years before the 2003 invasion. James Baker, who served as the first President Bush's secretary of state during the first Iraq War, has also signed up to advise the Bush campaign. Baker headed George W.'s political operation during the 2000 election recount fiasco. That, of course, took place in Florida while Jeb Bush was governor.

Those are the most recognizable names, but also the least likely to cross over into a potential new Bush administration. The presence of John Hannah, who worked as a top aide to former Vice President Dick Cheney, is more instructive. He was one of "56 leading leading conservative foreign-policy experts" who signed an open letter to President Barack Obama in 2012 urging the White House to arm Syrian rebels. George W.'s national security adviser, Stephen Hadley, also made the cut. He was a charter member of the infamous "White House Iraq Group," a collection of aides convened in 2002 to begin the process of building the case for the second Iraq War.

Also on Bush's team: former secretaries of the Department of Homeland Security Tom Ridge and Michael Chertoff, and former CIA chiefs Porter Goss and Michael Hayden. The latter, you might remember, repeatedly lied to Congress about the U.S. government covert post-9/11 torture program. Former Rep. Lincoln Diaz-Balart (R.-Fla.), a vocal Cuban-American critic of any attempt to normalize relations with the Castro government, is on Bush's team, as is Robert Zoellick, George W.'s choice to run the World Bank.

And those are just the names at the top of the page.

What's in a name? Many of President Obama's early supporters were disappointed when, soon after being elected in 2008, he appointed a slew of familiar names from past Democratic administrations to help manage and shape White House policy. In retrospect, those early decisions said a lot about how the new president viewed the task at hand, especially in dealing with major financial institutions. By hiring people with long histories on Wall Street, Obama signaled to the American public that cracking down on criminal banks was not a priority.

Bush's case is similar in many ways. Though he has now and will many times again assure the public that he is his "own man," the fact is that Bush's personnel decisions say a lot more about how he will govern than any 10 speeches.

The president is, by the nature of the job, called upon to manage domestic institutions and induce foreign ones from inside a deeply insulated pocket of influence in Washington, D.C. As the years pass, he or she will, inevitably, recede deeper into the confidences of trusted staff and aides. These are the people who prepare "briefing books" and calibrate "threat assessments."

If a leader is meant to consume information before making tough decisions, then the surrounding team works as a collection of high-powered chefs — in Bush's case, the candidate has signaled he wants his counsel cut and flavored with the same ingredients that fed his father and brother. And for the country, not to mention his campaign, that is a stomach-turning proposition.