50 Years After Selma, Voting Rights Are Once Again Under Assault Today

Fifty years ago Sunday, President Lyndon B. Johnson stood before a joint session of Congress in the evening and offered an uncompromising challenge to elected officials. During his speech, strategically titled "The American Promise," Johnson affirmed:

"There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem. And we are met here tonight as Americans — not as Democrats or Republicans — we are met here as Americans to solve that problem."

The problem he was referring to was the nonexistence of equal rights for black people in the U.S. One example of that inequity was the lack of federal protections to ensure black Americans had equal access to the voting booth.

In fact, eight days before Johnson gave his now-celebrated speech, 600 people gathered in Selma, Alabama, to march as part of a campaign led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

SNCC, SLCC and well-known leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., Diane Nash and John Lewis brought national attention to the bigoted practices used to keep black people from voting in municipalities like Selma.

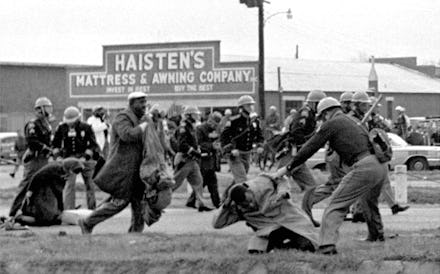

Alabama state troopers and local police met the protesters as they attempted to march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge to Montgomery. That Sunday was memorialized in American history as "Bloody Sunday." Protesters were beat with billy clubs and tear-gassed as people across the country watched on television. That moment, and the audacious activism of organizers, was the impetus for Johnson's fiery speech one week later.

"The brave grassroots organizing of the foot soldiers on the bridge led Johnson to assert that, 'The real hero of this struggle is the American Negro," Duchess Harris, Macalester College professor and author of Black Feminist Politics from Kennedy to Obama, told Mic. "His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation. His demonstrations have been designed to call attention to injustice, designed to provoke change, designed to stir reform.'"

And, yet, Johnson still had to offer a roughly 7,500-word speech after the events of Bloody Sunday to convince elected officials that federal protections were necessary to ensure equal access to voting for black Americans.

Johnson's efforts paid off. The Voting Rights Act was ratified in 1965.

"Like all major legislative reforms, the 1965 Voting Rights Act has a double historical meaning. It marked both the culmination of decades of activism and the origin point for ongoing battles to ensure that its promised reforms were enacted," Beryl Satter, professor of history at Rutgers University, told Mic.

Today, it is clear that the civil rights movement, and the subsequent legislative victories following it, were not enough to ensure the voting rights of black Americans remain protected. In June 2013, the Supreme Court gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act when it rendered its decision in Shelby County v. Holder.

"The Court's decision to gut Section 4 of the Act — which established a formula to not only identify the states wherein racial discrimination was most pervasive but also to promote stringent remedies where appropriate — sent shock waves through the black community. Like the recent march in Selma, it symbolizes the reality that the struggle continues," Luke Harris, associate professor of political science at Vassar College and co-director of the African-American Policy Forum, told Mic.

The court's decision has had dire consequences.

"Since 2011, every state but one has considered legislation that would make it harder for many eligible citizens to vote, and half the states passed new voting restrictions," Wendy Weiser, director of the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, wrote for the center. "By the 2014 election, after lawsuits and repeal efforts, voters in 21 states faced tougher voting rules than they did in 2010."

But what do the changes to the Voting Rights Act mean to freedom fighters today? What are the implications for contemporary organizers in the movement for black lives?

On the one hand, some organizers do not think voting, or state intervention, is a formidable approach to ending institutional racism and state-sanctioned violence.

Patrisse Cullors, co-founder of #BlackLivesMatter and executive director of Dignity and Power Now, told Mic, "Voting was never the viable option towards liberation for my community. My family bore the brunt of police repression and so the clearest place to organize was around ending state violence. The call to vote is often seen as away to placate more radical reactions to repression and subjugation of black people."

Yet, some organizers like Charlene Carruthers, national director of Black Youth Project 100, see a direct correlation between voting and transformative justice.

"The relationship between black people and citizenship was strengthened through the Voting Rights Act. While the relationship has always been tenuous and never fully actualized, organizing our vote is one important piece in a much larger strategy towards liberation. Voting alone will not save us, but for many of us, it can be an entry point into a broader movement," Carruthers told Mic.

Despite these differences within today's movement, the fact remains that some states like Alabama are pushing legislative agendas and new voting laws that will further disenfranchise many black Americans.

"Unfortunately, legislative victories like the Voting Rights Act can create complacency and justify inaction among those on whose behalf they were won, even as their opponents work ceaselessly to undermine them," Satter told Mic. "Social movements are needed to create legislative reforms, and they are also needed to protect such reforms, ensure that they function as promised, and build upon them to further tip the balance in favor of justice."

Political subjugation in the form of discriminatory voting laws is just as sinister as a system that allows some police to kill civilians with impunity or escape civil rights charges. And that is why movement work is as equally important as legislative intervention. Both are necessary to ensure we move forward as a nation and not backward.