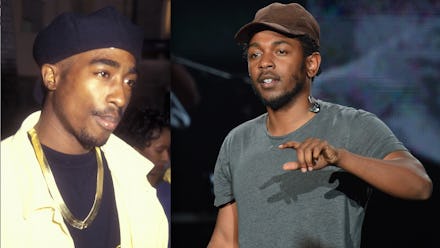

Kendrick Lamar's New Album Proves Tupac Is More Relevant Than Ever

Conceptually, lyrically and musically, Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly is miles ahead of most every hip-hop record from the past decade. It's been an absolute critical and commercial blockbuster. Most surprisingly, it's been able to top charts while including bold social and political commentary. Lamar has quickly defined himself as one of the most distinctive voices in our generation. His influence is clear, though: Lamar got his social conscience from Tupac Shakur.

Nowhere is Lamar's social consciousness more apparent than in the album's concluding track, "Mortal Man," when Lamar conjures a long-dead Tupac for a conversation. In a series of clips lifted from a 1994 interview with a Swedish radio host, Tupac offers some harrowing wisdom for Lamar's listeners. Within the span of a six-minute, partially fictionalized conversation, Kendrick Lamar shows exactly why we need voices like Tupac's now more than ever.

The conversation. Tupac saw the same need for social justice as Lamar does still. "I think that niggas is tired of grabbin' shit out the stores and next time it's a riot there's gonna be, like, uh, bloodshed for real. I don't think America know that," Tupac says at the end of the record.

His words have a powerful resonance in light of the protests surrounding last year's racially motivated police brutality cases, which resulted in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. There wasn't bloodshed to the degree Tupac predicted, but our conversations about racism have an urgency to them they haven't had in years.

But both the living and dead rappers see a solution: music as a means to influence society, of uniting history and contemporary art to affect social change. "Because the spirits, we ain't even really rappin', we just letting our dead homies tell stories for us," Tupac explains.

With this line, Tupac sums up the fundamental philosophy that he left hip-hop: Music can change people. And if one's raps are not honoring the legacy of those not fortunate enough to be with us — if it isn't socially conscious — it's not rap at all. That's the attitude that gave us Kendrick Lamar.

Taking responsibility with your words. For Tupac, hip-hop wasn't all about crafting a perfect lyrical flow and provocative hook; it was all about the change one could create with those raps.

"If we really are saying rap is an art form, then we got to be true to it and be more responsible for our lyrics," Tupac said in a 1995 Vibe interview. "If you see everybody dying because of what you saying, it don't matter that you didn't make them die, it just matters that you didn't save them."

He felt rappers should feel responsibility for pushing lyrical content that inspires and empowers those struggling against poverty and discrimination. Rap was more than just entertainment. But only a scant number of MCs agreed with that view in his day. And looking at the rappers that get the most buzz today — Iggy Azalea, Gucci Mane, Migos — there might be even fewer who agree with him now.

"How can they be talking about they so 'real' and they don't care about our communities?" Tupac said in 1995, as seen in the documentary, Tupac: Uncensored and Uncut - The Lost Prison Tapes. "Listen to the words that people say in their lyrics, and tell me if that some real sh—, if that's real to you ... Don't just bob your head to the beat, peep the game and listen to what I'm saying: Hold us accountable for it."

Lamar is Tupac's legacy. This unflinching accountability to himself and to his community is at the core of Kendrick Lamar's record. He struggles with his sense of responsibility to portray race and injustice in this country accurately rather than rapping about drugging and thugging. Throughout the album, he builds a poem line by line that describes his struggle: "I remember you was conflicted / Misusing your influence / Sometimes I did the same / Abusing my power, full of resentment."

The album is simultaneously Kendrick's journey towards realizing he has a responsibility to challenge and uplift his community with his music, while also offering perfect examples of what those insightful songs can sound like. He takes a penetrating look at the structural and cultural causes of racism on songs like "Blacker the Berry" and "You Ain't Gotta Lie (Momma Said)." In the latter, he poses an uncomfortable challenge to the rest of the hip-hop community: It's time to stop rapping about guns and drugs.

If that sounds like the sort of thing Tupac might encourage, that's because it is. In fact, Tupac brought these ideas to Lamar in a dream.

Two visions. Back in December 2013, Kendrick told GQ about a dream he had in which he was visited by a specter of Tupac: "I'm not huge on superstition and all that shit. That's what made it so crazy," he said. "Hearing somebody that you looked up to for years saying, 'Don't let the music die.' Hearing it clear as day. Clear as day. Like he's right there. Just a silhouette."

In that moment, Kendrick realized he had to be a conscientious voice for his community. "It wasn't just about money, hos, clothes, drinkin'," he told GQ. "I mean, I come from that world, but at the same time, I started to realize that there's people out there that can't really connect to that lifestyle. They're in the struggle."

This album is about that struggle. Lamar's inclusion of Tupac on the album is more than just mindless self-aggrandizement. It's a way for Lamar to align himself with Tupac's legacy of penetrating the heart of the most complex cultural and social debates of our time. It's a reminder that rappers have incredible responsibility.

It wasn't only Lamar who dreamed of Tupac, though — Tupac dreamt of Lamar, too. "I'm not saying I'm gonna change the world, but I guarantee that I will spark the brain that will change the world," Tupac once said in 1994 interview with MTV. Lamar might just fulfill his prophecy.

March 27, 2015, 6:44 p.m.: This article has been updated.