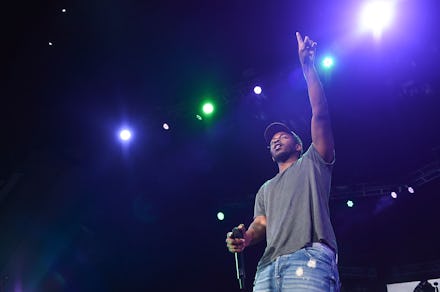

There's a Secret Message Hidden in Every Song on Kendrick Lamar's New Album

One of the most interesting parts of Kendrick Lamar's opus, To Pimp A Butterfly, isn't a rap at all. Throughout the album, Kendrick slowly unveils a poem, line by line, at the end of his songs:

"I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence. Sometimes I did the same," he recites after nearly every track. "Abusing my power, full of resentment. Resentment that turned into a deep depression... "

At the end of the record, it all comes together and poses the album's central question: What responsibility do artists have to their listeners? Lamar's response, across a 16-track journey that ends in the resurrection of Tupac, is resolute: Artists have a huge responsibility to their communities, and they're ignoring it.

Hip-hop's responsibility. "How many niggas we done lost bro? This, this year alone," Lamar asks on the outro to "i." "Exactly. So we ain't got time to waste time." Conversations about race and race relations have hit a cultural spotlight in a big way after the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner last year. Hip-hop, specifically, played a big role in Michael Brown's case, with a New York Times obituary suggesting that Brown's hip-hop aspirations somehow factored into the youth's untimely end.

This is a common theme. Sociologists and media figures have long blamed the genre's glorification of drugs, guns and violence for encouraging delinquency in the black community. And in a way, so has Lamar.

That's the sort of influence Lamar is tearing down on To Pimp A Butterfly. He plays out a parody of what he sees as hip-hop's lionization of wealth and violence on the album's opening track: "When I get signed homie I'mma buy a strap / Straight from the CIA, set it on my lap / Take a few M-16s to the hood / Pass 'em all out on the block, what's good?" he raps. "Uneducated but I got a million-dollar check, like that." But Lamar's own conclusion is that he must use his fame to spread knowledge and offer solutions to the problems his community faces. He decides he must lead by example, and determines that a traditional hip-hop example is flawed.

It's a similar conclusion that rapper Tupac — Lamar's idol and one of only a handful guests who shares vocal duties on the album — once came to before the end of his life. "If we really are saying rap is an art form, then we got to be true to it and be more responsible for our lyrics," Tupac told Vibe in 1995. "If you see everybody dying because of what you saying, it don't matter that you didn't make them die, it just matters that you didn't save them."

It "matters" because music has power. Music's effect on listeners can be difficult to measure. But several scientific inquiries have made it clear that lyrics and the images presented in music videos actually do have a poignant and measurable impact on listeners.

For example, an April 2014 study found that teenagers who like songs with explicit references to drinking or alcohol brands were twice as likely to have engaged in binge drinking than those who prefer songs with more sober lyrical content. Most surprisingly, teenagers' ability to recall these alcohol brands in song lyrics had as strong a correlation to drinking behavior as the influence of parents' or peers' drinking.

Additionally, an August 2014 study on music videos found that people who watch videos that portray "women as sex objects, and especially black women as hyper-sexualised 'endlessly sexually available' objects," have a greater tolerance of "racist, sexist and even rape tolerant attitudes," as End Violence Against Women wrote in a news briefing.

Artist's lyrical and visual choices clearly can and do drastically modify behavior.

But music can also affect listeners in a positive way. Organizations like Musicians Without Borders have used music to great effect to stem violence in some of the most divided locations in the world, including Kosovo, Tanzania and Palestine. Within our own borders, musical immersion programs like Los Angeles' Harmony Project can turn children away from gang violence and provide astounding cognitive benefits.

The Harmony Project introduces underprivileged from gang-ridden neighborhoods to classical and instrumental music as a way to give them alternative outlets for expression.

"It gives them something else to do, something else that they're about. Something that's about achievement. They set different goals," project founder Margaret Martin told NPR. "They actually say, 'I'm thinking about possibilities I never would have imagined.'"

Martin's words are oddly reminiscent of lines in the poem that ends Kendrick's To Pimp A Butterfly: "Finally free, the butterfly sheds light on situations that the caterpillar never considered, ending the internal struggle." Music can inspire listeners to reach higher and better themselves and their communities, and break the cycle of violence.

And if more messages like this were to come through in popular music, we really might change the world.

Lamar's role. On To Pimp A Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar has pledged his dedication to trying to bring this positivity to his listeners. Though his own assessment about hip-hop's responsibility for the systemic problems facing the black community is off, his willingness to take his music's impact seriously is exactly what we all need. Because music is a truly powerful force, and one of the most arresting facts Kendrick proved with the album is that music can be conscious and positive while still critically and commercially successful — something many rap fans have long insisted conscious rap could never achieve.

It's important that artists pay attention to the messages they push in their music, because it really may be one of the only sources of "hope that we kinda have left," as Kendrick claims on the end of the album. It's definitely one of the most universally accessible resources. Culture can be changed. It just takes artists and people brave enough to break the mold.