Rage Against the Machine Is Still the Protest Band Our Generation Needs

Last Thursday, Rage Against the Machine's lead singer, Zack de la Rocha, made a rare appearance in Run the Jewels' latest video, for their song "Close Your Eyes (And Count to Fuck)." He appears onscreen for only a few seconds, but the verse he delivers at the end of the song is one of the most compelling on Run the Jewels' album. It should remind everyone who hears it what a vital voice for protest he has always been.

To this day, Rage Against the Machine remains the most influential protest band of our generation. Few other "political" artists have challenged their listeners to seek truth and push back against oppressive political systems as earnestly as Rage Against the Machine. The legacy they left behind has inspired new generations of activists and protest musicians, yet no one yet has been able to push the same radical messages on the scale they achieved. They are the perfect template for modern protest music.

The sound. Rage Against the Machine never engaged in the bland, inoffensive activism that defines most rock star politics. As Al Mancini once noted in a piece on the band's legacy for ABC, there's nothing truly revolutionary about playing concerts raising money for AIDs, calling for an end to war or promoting voter registration. "It would be hard to find someone in favor of war or opposed to voting," Mancini writes. "The problem here isn't that the cause isn't noble — it's simply that the musicians are preaching to the choir, avoiding both the risk of offending anyone and the chance to change anyone's opinion."

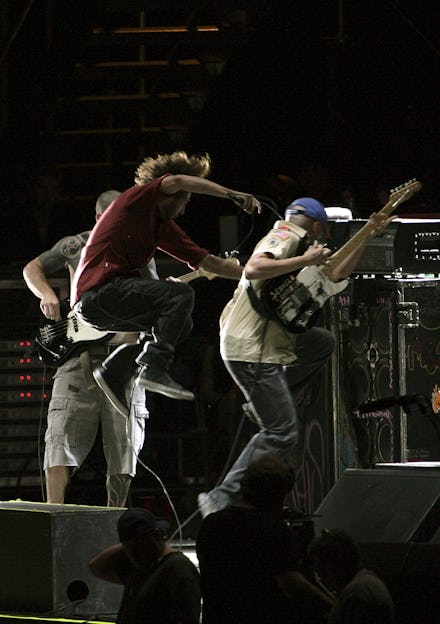

Rage Against the Machine pushed far beyond that. They threw themselves behind some of culture's most controversial causes. And yet, even though they were radical, they found tremendous commercial success. Now, their songs rake in millions of plays on streaming services (their famous "Killing in the Name" has over 39 million on Spotify) and they've earned serious chart success. Using their mainstream status, they brought these causes to audiences that may have never found them otherwise.

Their causes. In the late '90s, the band threw its might behind the campaign to free Mumia Abu-Jamal, a former radio journalist and Black Panther currently serving life in prison for killing a police officer in 1982. They immortalized him in their song "Voice of the Voiceless." In January 1999, the band played a benefit concert, with proceeds going to foundations dedicated to finding justice for wrongly accused. The concert met with stiff resistance from local authorities that threatened but ultimately failed to shut it down.

"It's not the first time that Rage Against the Machine has opened up a can of worms by standing up for what we believed in," Tom Morello, the band's guitarist, told the New York Times. "We've had the Ku Klux Klan protest our shows, but I didn't expect this from the governor of New Jersey's office."

Their visibility in Abu-Jamal case led to de la Rocha testifying against the United States' treatment of Abu-Jamal in front of the International Commission on Human Rights of the United Nations later that year in May 1999.

Rage showed the same support for the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, a Mexican guerrilla group, as well as Leonard Peltier, an imprisoned former leader of the American Indian Movement. Rage Against the Machine documented his case in the music video for their song "Freedom" and spoke to audiences about his imprisonment in long speeches at shows. Their agenda wasn't just a liberal one; it was revolutionary.

Organizing like activists. The band scheduled its shows to hit at key political junctures. They put together a free concert on the first night of the 2000 Democratic National Convention in a "specially designated demonstration area" across the street from the venue. Their protest was a backlash against the two-party system, claiming, "Our electoral freedoms in this country are over so long as it's controlled by corporations."

Similar protests followed outside both the Democratic and Republican conventions in 2008. After the band's performance on the first night of the DNC, the crowd morphed into a 9,000-person march led by veterans, according to the New York Times.

The band also paid careful attention to the timing and place of their 2000 music video "Sleep Now in the Fire," which protests income inequality. The band decided to "shoot the video in the belly of the beast," as the video's director, documentarian Michael Moore, described it — right on the steps of the Federal Building across the street from the New York Stock Exchange. The stock exchange shuttered its doors when the band tried to move its protest inside. Thankfully, "no money was harmed," as the band quips. The whole event foreshadowed 2011's Occupy Wall Street, which sought to dismantle the same economic systems.

The message before the music. To this day, Rage Against the Machine insists that the message comes first. When one-time Republican vice presidential candidate Rep. Paul Ryan said the band was among his favorites, Morello wrote an op-ed for Rolling Stone claiming Ryan understands nothing about their music.

"Some tune out what the band stands for and concentrate on the moshing and throwing elbows in the pit," Morello writes. "For others, Rage has changed their minds and their lives. Many activists around the world, including organizers of the global Occupy movement, were radicalized by Rage Against the Machine and work tirelessly for a more humane and just planet. Perhaps Paul Ryan was moshing when he should have been listening."

Few artists today write music as confrontational and incisive as Rage Against the Machine's. Few take it as serious of a tool for orchestrating political change. Hip-hop guru Questlove noted this absence in a December Instagram post, writing, "We need new de la Rochas!" He couldn't be more right. We need more voices to help further the principles laid out by #BlackLiveMatter and the brief but brilliant Occupy movement. Rage Against the Machine lit that political torch under rock music. It's time that flame caught again.