The Story of How Bernie Sanders Became Famous Will Make You Love Him Even More

Sen. Bernie Sanders' (I-Vt.) bid for the presidency has been a long time in the making.

The firebrand politician, who will turn 74 in September, came from humble beginnings in Brooklyn. He's been demolished in several political races in his life, and every time he has won one — whether for mayor, the House of Representatives or the Senate — the establishment widely assumed the victory to be a short-lived stroke of luck.

And yet he has prevailed, winning reelections against the predictions of his critics and garnering national attention, despite lacking the kind of charisma one would expect of a politician stigmatized for identifying as a democratic socialist.

Now, as his campaign for president ramps up, he's already making a splash. He's in Iowa talking about the yawning gap between the rich and the poor. He's on Sunday morning talk shows talking about free college and health care. He is waging a rhetorical war against "the billionaire class," whom he believes Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton will side with at the expense of the middle class.

As he goes about building his campaign for president, it's worth taking a look at where he's from, and how he got here.

The beginning: Sanders was born in 1941 and raised in a poor Jewish family in Brooklyn. His father, a Polish immigrant who was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust, was a paint salesman who struggled to make ends meet. According to the New York Times, he slept in the living room with his brother in his family's one-bedroom apartment in Flatbush, and, he told the New York Times, "money was always a source of friction." His mother, who always hoped to escape that apartment, died at the age of 46.

Sanders' taste for attempting long-shot political races on a radical platform emerged early in life. In high school, he ran for class president on a "platform to provide scholarships to war orphans in Korea," according to the University of Chicago Magazine. He came in third place.

In the '60s at the University of Chicago, where he transferred after a year at Brooklyn College, he studied psychology and took on leadership roles in the radical political scene. "When I went to the University of Chicago, I began to understand the futility of liberalism," he told the Los Angeles Times in 1991. According to Chicago magazine, he helped lead a sit-in against racially segregated campus housing, and worked as an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In 1963, he took his first trip to the nation's capital to march in Martin Luther King Jr.'s seismic "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom."

After college, Sanders lived briefly on a kibbutz in Israel, and then went on to buy "85 acres of woodlands in Middlesex, Vermont, for $2,500" with his college girlfriend, who would eventually become his first wife, according to Chicago magazine.

Entering the fray: In Vermont, Sanders maintained his radical political vision while making his first attempts at public office. As the New York Times Magazine notes, his early political career was as notable for its ambition as it was for its failures:

He was an early member of Vermont's Liberty Union party, an offshoot of the antiwar movement in Vermont. He ran as the party's nominee for the Senate in a special election in 1971 and finished with 2% of the vote. The following year, he ran for governor and received 1%. He would run two more times for statewide office that decade as a third-party candidate and never come close.

Things took a turn for the resolute socialist during the Reagan era. As the country embraced a man who sought to identify communism as the world's greatest evil, the largest city in Vermont turned to a man who was driven by faith in socialism as a force for a more virtuous society.

In 1980, Sanders ran for mayor of Burlington, Vermont. It was in this campaign that Sanders' political strengths finally came to the fore: the ability to win the trust of voters by tirelessly going door-to-door, and understanding the concrete problems that afflicted them, no matter how minute. He managed to eke out a win over the incumbent mayor by a dozen votes, according to the New York Times Magazine.

As mayor, Sanders pursued initiatives true to his enterprising socialist sensibility, but he won over his constituents by effectively attending to less glamorous everyday issues, like filling potholes. Burlington residents could — and did — call him on his phone in the middle of the night about any kind of grievance. Sanders quickly developed a reputation as almost superhumanly industrious, and a champion of useful initiatives for working people like expanding dental care access. He was reelected twice.

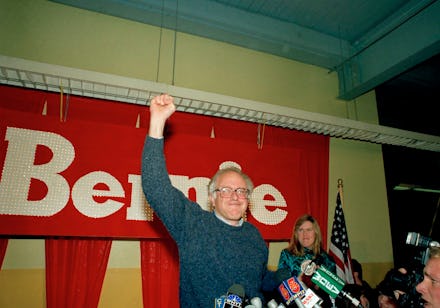

Bernie goes to Washington: Sanders then set his eyes on Congress. He failed to win on his first attempt, but in 1990, he was elected to be Vermont's sole representative in the U.S. House of Representatives. As an independent, he initially alienated most of the Democrats with his fiery rhetoric about the systemic corruption of the party system, but soon he learned how to play the game.

In the House, where he spent the better part of two decades, he co-founded the Congressional Progressive Caucus, which convened the most left-leaning Democrats in the lower chamber. Sanders' brazen political style and strong base in Vermont proved an asset for the party he never joined but grew to work with productively. As the University of Chicago Magazine put it:

Though he was the House's only member unaffiliated with the Democrats or Republicans, after the Democrats lost control of the body in the 1994 election, he proved enormously useful as a leading spokesman against what they saw as the ravages of Newt Gingrich's Republican revolutionaries.

In 2006, Sanders made a leap to the upper chamber, winning a seat in the Senate with a 33-point victory over his Republican opponent.

In the Senate, Sanders has continued to play the role of left-wing gadfly as an independent, but has voted with the Democrats. In 2010, he famously lambasted the deal that the Obama administration struck with the Republicans over extending the Bush tax cuts in a marathon filibuster that lasted more than eight hours. The speech went viral, and was promptly dubbed "the filibernie."

Sanders hasn't been a pure agitator. He has, for example, negotiated bipartisan deals on veterans' benefits, and successfully secured a special waiver to allow Vermont to pursue an experiment in single-payer health care when Congressed passed the Affordable Care Act. But Sanders does not yet have any major piece of legislation to his name.

What's next: These days, Sanders is back in campaign mode. He's railing against the banks, and he's championing the everyman. The mainstream media may think he's out of touch — this is a man whose Capitol Hill office hosts a photo of Eugene Debs, the 20th century socialist who ran for president five times and never had a chance. But Sanders has proven time and again that labels tend to fade from view when the public finds a figure trustworthy and compelling.

The hunger that's driven Sanders since his Brooklyn days still drives him. And there are more than a few signs that the public is craving something different than the usual fare.