10 Years Ago, My Mathematician Father Sent My Name to Pluto — And I've Finally Arrived

One August evening in 2005, a few weeks shy of my 14th birthday, my father came bounding down the stairs into our living room with a piece of paper in his hands. "You're going to Pluto," he told me, grinning.

I looked at him, screwing my face up into a superb teenage scoff. "What?"

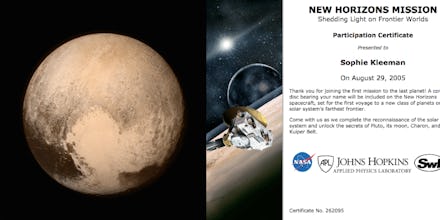

He handed me a printed certificate, titled "New Horizons Mission." It showed a spacecraft drifting through a black, star-strewn cosmos. "Thank you for joining the first mission to the last planet," it read. New Horizons, my father excitedly explained, was the name of a mustard-colored spacecraft headed for Pluto and the rest of the Kuiper belt, a ring-shaped stretch of icy, celestial bodies that extend beyond our solar system. It would explore a new world, he said, a planet — at the time — we knew little about.

My name, as well as the names of over 430,000 other people, is engraved on a compact disc that departed aboard New Horizons in 2006. On Tuesday morning, it passed Pluto, on the outer reaches of our solar system, roughly two and a half billion miles away from Earth.

For almost 10 years, New Horizons has been a kind of oddball totem I used to signify time as the years went by. There were moments the mission seemed unfathomable, like a stretch of time that would never actually come to pass. But this month, as the fanfare surrounding the mission hit a fever pitch and images of the dwarf planet grew clearer by the day, that night in August came into sharper focus, and so too did my mathematician father.

The two of us have always spoken different languages. We share the same navy blue eye color, the same thick, cow-licked hair and the same workaholic tendencies, but where I speak in words and quotations, he speaks in numbers and theorems.

He has always loved the practical, the rational — the ideas he could connect together on a page or a chalkboard. When I was a little girl, I studied the papers and books on his desk, thumbing through them as I tried to understand their mysterious dialects. I felt as though I was handling some sort of prized alien artifact, and when friends came to visit, I pulled them into his office, proudly pointing to the formulas and musings I hazily recognized, even then, as part of his core.

During an era in which funding for American space exploration always seems to be in flux, New Horizons represents a concerted effort to convince us of its pricelessness.

As a mathematician, he directs his attention to the practical applications of numbers and equations. But it was his former life — his PhD is in theoretical physics — that I found the most exciting. At the peak of my preoccupation, when I was 10 or 11 years old, we used to sit for hours after dinner exploring the unknowns of the universe. He taught me what a black hole was, what would happen once the sun stopped burning, whether we were close to finding alien life. He gently explained that our entire universe was an unfathomable, ever-expanding swath of stars and matter that suddenly, inexplicably and wonderfully, appeared out of dust.

It fascinated me. I understood very little of the science behind it, but from a distant, bird's-eye view, it was beautiful, like the music of that language I didn't speak.

When I recently spoke to my father about New Horizons, he said adding my name to the list was intended as a kind of spark. "I was really into it, so I thought, yeah, the kids might be into it as well. It was a way of getting your imagination going," he told me.

But by the time the New Horizons mission rolled around, my interest in outer space had waned, replaced by the Doors and the Boston Red Sox. When my father presented me with the certificate, I wasn't as thrilled as I would have once been. Pluto seemed about as relevant to me then as plant life in Outer Mongolia — that is to say, not at all.

But as the years went by, I found myself returning to it. I occasionally came across news stories about it, and my father would update me every so often about its progress. He has never traded much in sentimentality — he comes from a long line of engineers and academics, after all — but the gesture of adding my name to the list, I came to realize, was his version of that.

Others, I discovered, had realized a similar feeling. "When the opportunity arose to have my name permanently included on the trip to Pluto and beyond, there was absolutely no hesitation," 28-year-old Christian Ponte, whose name also flew by Pluto on Tuesday, told Mic. "I've been waiting for us to visit Pluto for most of my life, so the fact that we're just about there is nothing short of thrilling."

"Unless New Horizons has a head-on collision with some star in the far distant future, my name will be floating around the Milky Way galaxy long after the Sun and Earth are dead and cold," Bob Tregilus, 57, another New Horizoner, told Mic.

There are things out there we don't yet have the answers to.

Pluto, the New Horizons mission has made clear, still occupies a space in our consciousness, despite its downgrade from a planet to a dwarf planet. Hovering around the outskirts of our solar system, it's the celestial version of the one that got away. For many, it's the tiny, icy orb that flitted off before we had a chance to discover what it contained.

"Pluto kind of represents the end of our home environment," Gia Milinovich, 46, who put her and her son's name on New Horizons, told Mic. "Any further out and it's deepest, darkest, 'empty' space. That's why I think people were so upset when it was downgraded: Our home in the universe became a lot smaller then."

Our nostalgia is evident in the materials on the spacecraft itself. Besides the list of names, New Horizons also contains a small parcel of the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the astronomer who discovered Pluto in 1930 at the age of 24. Andy Cheng, the principal investigator for the spacecraft's Long Range Reconnaissance Imager, described its importance in the passing of time. "A big fraction of your whole life is what one of these missions takes," he told the Washington Post. "You just have to teach yourself: Wait. Just wait. Be patient. It's a very long time."

Part of the appeal, besides the sentimentality, is the existence of the unknown. My father put it this way: "I've been interested in space exploration for a long time, and this was the last piece of the puzzle." We know how the inner rocky planets and the outer gas giants work, but New Horizons intends to find out how Pluto and other objects like it fit into our solar system.

The mission gets to an essential curiosity inherent in space exploration: It reminds us, in a way we can actually be part of, that there are things out there we don't yet have the answers to. And during an era in which funding for American space exploration always seems to be in flux, New Horizons represents proof of its pricelessness.

Pluto, for all its admirers, will remain suspended in the Kuiper belt, just as it has been since Clyde Tombaugh spotted it in 1930. New Horizons will meander on, farther out into the ring of icy objects, sending back bits of information as it goes.

Although those 10 years have finally come to pass, it won't cease to be my quirky timepiece. It will still be out there, floating in the ether, with my name, thanks to my father, along for the ride.