Infectious Disease Experts Are Warning About a Possible Future Pandemic We Can't Control

Not everything that gets frozen alive stays dead.

A team of French scientists is resurrecting pathogens from the last Ice Age and cautions that their findings indicate potentially hazardous pathogens could thaw in Siberia.

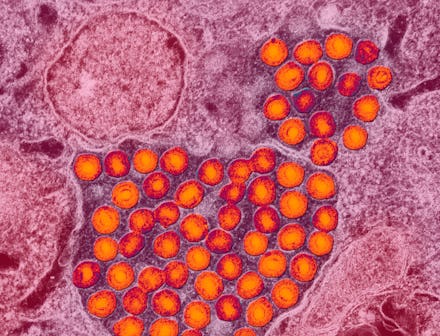

Researchers from the University of Aix-Marseille's National Center of Scientific Research have isolated an amoeba-killing virus called Mollivirus sibericum in a 30,000-year-old chunk of Russian permafrost. It's the fourth new type of giant virus (viruses with complicated genomes that are large enough to be visible under common optical microscopes) to be discovered since 2003. It's also the second to be isolated from the same sample of permafrost.

The researchers write in their study that like another permafrost virus they discovered last year, Pithovirus sibericum, they believe the pathogen can be brought back to life. By exposing the ancient virus to the single-celled amoebas, the scientists hope to entice any remaining contagious particles of the bug into leaving their dormant state.

Here's where it gets worrisome: Mollivirus is completely benign, but scientists really don't know what else may be lurking deep in the Siberian permafrost. Permafrost in Siberia is melting at an alarming rate thanks to global climate change, thought to be the cause of gigantic, mysterious holes in the ground discovered last year on the region's Yamal Peninsula.

As global warming both melts the permafrost and opens areas of northern Siberia up to increased resource extraction activity, many frozen microorganisms could reawaken.

"Mining and drilling means bringing human settlements and digging through these ancient layers for the first time since millions years. If 'viable' virions are still there, this is a good recipe for disaster," lead researcher Jean-Michel Claverie wrote to Mic. "Permafrost is not ice. It is much richer in microbes of all kinds, and a much better preserver than ice. Everything is everywhere, as microbes go, and there is no more no less virus there than in other places."

It's hard not to be reminded of the opening scene of 1998's The X-Files movie, in which a young boy encounters a long-hidden cache of a sinister disease called the black oil in a cave.

"A few viral particles that are still infectious may be enough, in the presence of a vulnerable host, to revive potentially pathogenic viruses," Claverie told Agence France-Presse. "If we are not careful, and we industrialize these areas without putting safeguards in place, we run the risk of one day waking up viruses such as smallpox that we thought were eradicated."

He noted that in addition to unknown diseases, permafrost could contain eradicated viruses like smallpox. That would be extremely bad news for humans, most of whom no longer receive smallpox vaccinations.

Luckily for us, the risk is probably very low. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spokeswoman Callie Carmichael told Mic the CDC is not particularly concerned about frozen viruses, though the topic does "fit in our broader efforts to monitor emerging and re-emerging diseases globally."

"Climate change is causing shifting vector ranges, altering distribution of vulnerable populations (both human and animal), and generally changing disease patterns," she said, "all of which CDC actively monitors to detect disease threats."

According to Columbia University microbiologist and infectious disease specialist Vincent Racaniello, humans have better things to worry about than ancient plagues bubbling up from mysterious chasms in backwoods Siberia.

"There is zero worry" about the kinds of viruses being studied by the NCSR team, Racaniello told Mic. "They're big viruses, they are really interesting, but they do not infect people ... until we have some evidence that there are some viruses there that can infect people, the possibility that there is one there is very low."

Racaniello said viruses circulating around the world (including in environments like kitchen freezers) right now are much more dangerous. Virologists are constantly discovering new pathogens in animal populations across the globe that attract much less attention. "I'm more worried about viruses that are actually out there that are pathogenic," he said.

Claverie, however, believes there is a "non-zero probability that the pathogenic microbes that bothered [human ancestors such as Neanderthals] could be revived, and must likely infect us as well."

"Those pathogens could be banal bacteria (curable with antibiotics), or resistant bacteria, or nasty viruses," he said. "If they have been extinct for a long time, then our immune system is no longer prepared to respond to them. So yes, that could be dangerous."