We Asked White Feminists to Discuss Mistakes They've Made. Here's What Happened.

Whether it's a boo-boo or a fuck-up, no one is immune from making mistakes, or feeling shame.

Luckily, science says mistakes make us smarter. A mistake can be a transformative event; it gives us perspective. It can be scary to make a mistake in a time when Meryl Streep wears a T-shirt with the word "slave" on it or Taylor Swift interrupts Nicki Minaj on Twitter.

Mistakes can be conversation starters, not conversation enders. Mistakes not only make us smarter, they can make feminists better feminists. In an article for Everyday Feminism, Jarune Uwujaren and Jamie Utt praised mistakes as the key to white feminists understanding intersectional feminism.

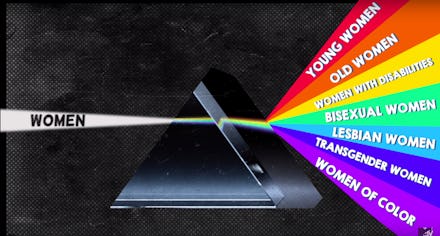

What is white feminism? Feminism that excludes the experiences of women of color, as well as women of other marginalized identities. It's a feminism based in privilege. Don't worry, though — just because you're white doesn't mean you're a white feminist. It's an ideology, not a population.

Let's take a long hard look at our thoughts and actions: The road to intersectionality begins in the mirror. Self-reflection can be one of the greatest tools available to a feminist willing to grow. Self-reflection requires that we understand what challenges us and "the desire to learn about issues and identities that do not impact us personally," according to Uwujaren and Utt.

Mic asked our readers, specifically those who have previously practiced white feminism, to tell us about the mistakes they've made and how it made them better feminists.

"I used to overuse of the word 'ratchet' for a short period of time, and I had an obsession with twerking. Then I'd ask, 'Why aren't we over racism yet? How have we not risen above yet?' I've learned a lot since then. It was simply ignorance and living in my own little 'la la land' and I'm glad I know better now. I think we all need to be more self-aware and empathetic. I've learned to listen more and pay closer attention to the words I actually say."

"In Buenos Aires, Argentina, walking down the street with a friend of mine, I said that the Argentine women might actually like catcalling. Why would Argentine women feel less insecure and harassed by strange men yelling after them on the street? I wish I had not said that."

"Through feminism I became aware of intersectionality and my own white privilege. I know I look back and cringe at when I asked my black friend if I could touch his hair and told him that I thought I might have black ancestry. I never considered myself racist, but I had no concept of the issues black people face on a daily basis. I'm British and sometimes I think the lack of racial tension here compared to the States makes us complacent and forget history. But here too we must recognize white privilege, as my past behavior shows."

Who's at the center of the narrative: One of the main gripes many people had with the Minaj-Swift exchange, including Minaj herself, was that Minaj never mentioned Swift, but Swift decided she was part of the discussion. In their article, Uwujaren and Utt remind us that without self-reflection, "it's easy to center feminism around either our own experiences or the experiences of those who are already the most privileged in society."

Plenty of Mic readers shared stories about times their world views changed:

"I remember talking to a girl in my class who was wearing a hijab and asking obnoxious questions. I hadn't realized that women who wear hijabs, or any other type of head covering, choose to wear them because of religious reasons and not because they're oppressed. Thinking back it makes me cringe. I wish I hadn't acted so high and mighty. I probably would have not interrupted her and just listened to what she had to say."

"I used to use the word 'sketchy' without even thinking. I later realized that 'sketchy' is a word people use, myself included, to describe areas with people of color and/or poor people. Once I made this connection, I stopped using it. When I spoke of places I previously deemed 'sketchy,' I made an effort to talk with empathy and compassion for the people who live there."

"I used to roll my eyes at people calling others out for cultural appropriation for things like clothing, makeup, hair styles and music. After I read more, my eyes were permanently opened. I could see what I'd been missing. I could see that I'd been blinded by the privilege my race had afforded me. I finally understood the seriousness and the wrongness of it all. That by boosting oneself up by using bits and pieces of the culture of another race, damage was being done. That the damages done in the past were being ignored or trivialized. This isn't a silly issue. This isn't some meaningless scheme to take anything away from anyone. This isn't POC punishing white people for being white."

"I live in St. Louis, and an employee in my office was talking about printing some T-shirts that would read, 'My life matters' to hand out during protests in response to the events in Ferguson. I don't remember exactly what I said, but it was something along the lines of, 'That doesn't make sense for me. Will you make one I can wear?'

"I realized I'd approached the conversation from how it affected me, when it had nothing to do with me. In that moment, I was more focused on my place in the movement than the movement as a whole. It was mostly a misguided form of support. I apologized shortly after, and now make conscious decisions to only support and not speak over voices of those who are already telling stories."

You can't fear mistakes: One of the main points of Roxane Gay's book Bad Feminist is that every feminist is, at some point, a bad feminist. And, in that spirit, Uwujaren and Utt come out and say plainly: "There's no room for perfection in feminism." If we never fail, that means we've never made an effort, according to Uwujaren and Utt. Rather than being scared of failing — or chastising people for failing — feminism requires failure.

"I dated a black girl, and in retrospect I was completely unaware and insensitive to her needs as a black queer college student next to my comparable place of privilege. I saw her trying to cope with humor and self-deprecating jokes about her blackness in our group's sea of white ... and I admonished her for it. I wish I would have facilitated conversation and acknowledged the root of it. I should never have dismissed her jokes about being the 'token black girl,' or acted as though she was doing herself a disservice for the jokes about her being different in ways of privilege."

"I didn't understand or realize that the kinds of responses we were crafting in the battered women's movement did not include the needs or concerns of women of color. We focused on police intervention, changing laws, court orders, etc., without realizing that these very systems were abusive and coercive towards WOC, rather than protective and responsive, due to racism. We thought we were working for 'all women,' which is like saying that all women are the same. We understood sexism and misogyny, but we did not understand systemic racism, nor did we understand our own racism.

"I feel shame and regret that white feminists were (are) unaware of their white privilege/racism. I am horrified by some of the tools we fought for that increased the danger for battered WOC and their children (mandatory arrest, for example), and my efforts are now re-directed based on the narratives of WOC."

"In my intro to women's studies course, I made an unfortunate statement in response to a story a student shared. I said, 'anybody can be racist.' A student quickly called me out and clarified to the class that it takes the support of a privileged position to be able to 'be racist.' I thanked her in front of the class and later personally as well. I asked the class if they understood why what she was saying was so important. I made a mistake — I was hoping to convey that, in our culture, anyone can internalize the ideology of the harmful dominant paradigm, even if they consciously object, this hegemonic negativity can still flow through them via the symbolic realm; through word choices, there can be unwitting collusion. That is not what my words conveyed and the student turned it into a teachable moment."

Not everyone who wrote to Mic was a white person. While we did not ask for people's race, some people who came forward did explicitly state that they were feminists who were not white.

"I am not a white woman, but until learning about intersectionality, had a lot of beliefs that corresponded to exclusionary white feminism. I took pride in not being like the 'other' women of color. I would distance myself from my own culture's traditional practices. I hated the color of my skin for years. Every time we learned about women's rights in high school it was all respectability politics and the invisibility of racial issues. I am disheartened when I look back, but am grateful that I have a much greater awareness of the world now. With awareness comes a lot more anger. But sometimes anger is good if it means we are able to speak out about injustice."

— Sanam Sitaram, 22

Thank you to everyone who wrote in and was willing to reflect, take themselves out of the center and make mistakes. If you have any more questions about intersectionality, check out the video below. And don't be afraid to make a couple mistakes.