Scientists Find Malaria May Hold the Key to Fighting Cancer

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen and University of British Columbia believe they have developed a novel cancer treatment — and they owe it all to malaria, a deadly parasitical condition that causes nearly 600,000 deaths a year.

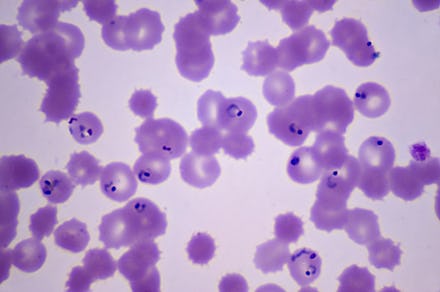

In a statement on the University of Copenhagen's website, malaria expert Ali Salanti explained the research team isolated a protein used by malaria parasites to attach themselves to a pregnant woman's placenta. The protein adheres to a carbohydrate in the placenta that's indistinguishable from one found in many types of tumors.

When the team used the protein as a delivery vehicle for a cell-killing toxin, they were able to effectively target and kill cancer cells in mice. The treatment assaulted over 90% of tumor types tested, including three varieties of human tumors that had been implanted in the rodents.

The results were published in the journal Cancer Cell.

"For decades, scientists have been searching for similarities between the growth of a placenta and a tumor," Salanti said in the statement. "The placenta is an organ, which within a few months grows from only few cells into an organ weighing approximately two pounds, and it provides the embryo with oxygen and nourishment in a relatively foreign environment. In a manner of speaking, tumors do much the same: They grow aggressively in a relatively foreign environment."

According to researchers involved in the study, the correlation led them to remarkable results.

"It appears that the malaria protein attaches itself to the tumor without any significant attachment to other tissue," Ph.D. student and contributor Thomas Mandel Clausen said in the statement. "And the mice that were given doses of protein and toxin showed far higher survival rates than the untreated mice. We have seen that three doses can arrest growth in a tumor and even make it shrink."

While the method sounds miraculous, in reality, the history of cancer research is littered with similar discoveries that simply never panned out. io9's Charlie Jane Anders writes cancer has consistently proven more difficult to fight than scientists anticipate, since drugs which seem promising in early animal studies often fail in humans.

"Obviously you're excited [when a drug works on mice]," University of California, Davis, Cancer Center Director Ralph deVere White told Anders. "But the problem is that 95% of those new drug applications fail. They don't get FDA approval. Seventy percent of them fail in that Phase I, which is the toxicity study. That leaves with you with 30%. And then 60% of those fail, and [most] of the time, it's because they don't work. That's nobody's fault. It isn't surprising that progress is slow."

In the statement, Salanti said that testing in humans was at least four years away, but added that the researchers were optimistic the treatment may eventually join the cancer-fighting arsenal.