This Halloween, I Dove Into the New York Seance Scene in Search of Demonic Possession

Like most millennials, I first learned about the "other side" from Miss Cleo. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the television seer doled out relationship advice and even paternity tests. Invoking the power of tarot cards, Cleo regularly tapped into the spiritual realm to offer her clients enlightened answers.

"My first experience with connecting to somebody on the other side was my uncle, Kane, and it was at age 14," Cleo, a self-described "voodoo priestess" who now goes by the name Y. Cleomili Harris, told Mic.

The other side: Every year around Halloween, the supernatural gets renewed interest by thrill seekers and the general public looking to get into the spirit of the holiday. Cemetery tours, haunted hayrides and Hocus Pocus marathons proliferate across the country in a celebration of the paranormal and otherworldly.

But is it all just for fun, or is it really possible make contact with the dead who have messages for the living? For professional mediums, seers and psychics operating in the $2 billion psychic services industry, there's nothing fun or funny about the other side. Some warn of serious consequences while toying with spirits, either via Ouija boards or formal seances.

Though she is known primarily as a television psychic, Harris said she has conducted seances in the past. "Everyone that I've had has been successful in contacting the people we're trying to contact," she said.

The risks, said Harris, are real.

"We do believe in possession, and we do believe in negative energy," she said. "You can come back with nightmares, you can come back with a presence that can follow you out of the seance."

Well, Ms. Cleo — challenge accepted.

60 Pine

Seeking a seance on a deadline, a friend suggested I head to the Shanghai Mermaid gathering on 60 Pine Street in Lower Manhattan, New York City, for a seance-cum-Victorian bacchanal. The space is owned by the considerably more staid Down Town Association — a member-owned social club which deems itself an "island of quiet civility" — but is frequently rented out for private events.

On the event website (now offline), I was promised a "darkly elegant soiree, on a most unusual night. This night occurs during that very brief time of year, when the veil between the worlds is at its thinnest ... a time when the living and the dead are terribly close."

The evening was scheduled to stretch from 10 p.m. until 3 the next morning. Seances took place on the second floor up an elegant staircase under the guidance of medium Madame Blavanskaya — the name an homage to the 19th-century Russian seer Yelena Blavatskaya — but known as Djahari Clark on Twitter.

Mic reached out to Clark, who was unavailable for comment.

I sat at an elongated table, my glass filled with cheap sparkling wine. On either side of me, gooey hipsters draped in pricey overcoats from Gothic Renaissance did their best to sound like first-class passengers on the Titanic. Flashes of lightning illuminated the room, thanks to a projector near the door.

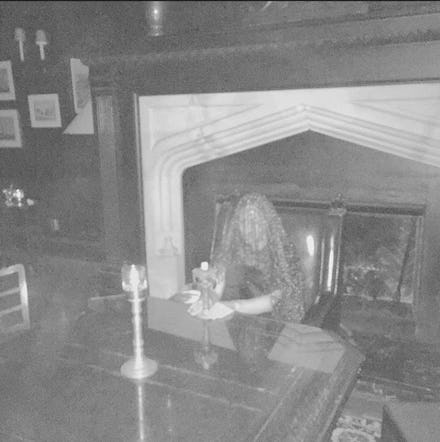

Shrouded in a black veil, Blavanskaya, who at various points during the festivities hailed from the "Eastern Bloc" and/or "Chernobyl," sat at the head of the table. In a shrill voice she summoned a spirit. "Murder!" she shrieked. "Murder!"

From behind a dressing screen we heard a slight whimpering, and a woman draped in white came forward holding a candlestick. Following some more shrieking, the woman came up behind me and placed the candlestick on the table. To the soundtrack of shrieks, whimpers and the din of partygoers in another room, the woman in white gracefully exited. About an hour later, I think I saw her at the bar.

In another seance hosted by Blavanskaya later that night, I sat through what was essentially the same exact routine.

"I wanted to get dressed up, and I like cool things," said Chantel Nanton, who sat next to me. "This wasn't necessarily a seance, this was a woman in a costume."

Nanton, like most other partygoers, didn't mind the less-than-authentic atmosphere. "I'm here for the drinks," she said. Indeed, by the end of the night, the most memorable spirit that entered my body was a mystery shot which I believe was Jägermeister.

A Uniquely American Tradition

"We have good documentation that [Abraham] Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd, held at least one, maybe two seances in the White House," Mitch Horowitz, a historian of alternative spirituality and author of the book Occult America: White House Seances, Ouija Circles, Masons and the Secret Mystic History of Our Nation, told Mic. "For Mary Todd Lincoln, it was a matter of grave seriousness." In 1863, President Lincoln went so far as to invite a reporter from the Boston Gazette to attend his "spiritual soiree."

According to Horowitz, seances, a word which loosely translates from the French for "session" or "sitting," originated in 18th-century Europe but rode a wave of popularity in America during the 1850s and 1860s. The traditional rules of a seance are traced back to the American spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis, who outlined them in his 1851 book The Philosophy of Spiritual Intercourse: Being an Explanation of Modern Mysteries. Helpful images appeared in a follow-up work, The Present Age and the Inner Life, in 1853.

"That's where we get our image of Victorian-age folk joining hands in a darkened parlor, trying to summon the dead," Horowitz said. "That image has never left."

The fad gradually fell out of favor after the 1887 Seybert Commission report. The inquiry and subsequent findings issued by faculty from the University of Pennsylvania investigated a number of celebrated spiritualists of the era, and determined every single one to be a sham.

"I have been forced to the conclusion that spiritualism, as far at least as it has shown itself before me ... presents the melancholy spectacle of gross fraud, perpetrated upon an uncritical portion of the community," wrote

Today's skeptics have not strayed much from Fullerton's assessment.

"Anybody can talk to the dead; it's getting the dead to talk back that's the hard part," Michael Shermer, the publisher of Skeptic magazine, told Mic. "There's not a shred of scientific evidence that ghosts are real or that seances work."

In a modern retelling of the Seybert findings, Shermer completely dismissed the idea that anyone could be a spiritual medium and that voices and moving tables were more than likely the result of chicanery. "They're just magic tricks," he said. "No different than when [David] Copperfield walks through the wall."

The Church

Haters notwithstanding, I was going to try again. After all, if it was good enough for Honest Abe, it was worth another go for me.

Far more serious ceremonies are held at Midtown Manhattan's Spiritualist Church. Since 2007, the church has provided seances to interested parties on Sunday evenings after services in an upstairs assembly hall. A visit today costs $20.

The room was spartan: A covered piano and small bookshelf sat below a modest performance stage. The rest of the area was dedicated to a circle of black chairs. In the center of the circle was a small table holding candles and a small horn.

Congregants filed in gradually until almost every seat was filled. Far from Victorian dandies, these were ordinary people. Few seemed under 40; many were well beyond that.

Steph Wild and Nilsa Ocasio led the seance from two chairs by the front of the stage. Things got going around 8 p.m. Ocasio dimmed the lights and led the group in an opening prayer where she exhorted participants to imagine being shrouded in white light.

Then: "May I give you a message?" Ocasio said, motioning to a participant. After receiving an invariable "yes," the medium launched into an opaque, and often rambling, series of thoughts or observations she claimed to receive from the spirits. "Can I leave you with that?" she said. Again, the answer was yes.

"May I give you a message?"

Ocasio and Wild traded off with this routine for the duration of the seance. In some cases, the mediums attempted to divine more specific details: a grandfather named Albert, an older male relative who was a police officer. At first they asked participants whether these details resonated. After a few embarrassing strikeouts, they stopped asking.

The whole process vaguely resembled being picked for a middle school dodgeball team. As I sat silently, waiting for my "message," my mind went furiously through the Rolodex of the deceased in my life who I would be curious to hear from: grandparents I never knew, an old music professor, my labrador Maggie.

Given my experience with dodgeball team-picking, I fully expected to be called on last, if at all. But Ocasio's finger eventually waved at me, a paying customer, from the darkness.

I was barred from recording, but her message to me was something along the lines of: I'm a writer often placed in situations I'm not necessarily interested in being in but should approach with an open mind to see what I can get from it. Given that I disclosed to the seance organizers that I was a journalist beforehand, I was more than a little skeptical.

Translated from "spiritualese," Ocasio's words were unambiguous. "Please write nice things about our seance; please give us a good review on Yelp."

And that was it. Other messages came and went, but not for me. Then, in the darkness, I suddenly felt possessed by a demon I knew well — boredom.

And so in the End

There were no nightmares, there were no spirits, there were no ghosts or head-spinning demonic possessions. If I am being followed by an evil spirit like Christine Brown in Drag Me to Hell, it has yet to make itself known.

So was Miss Cleo wrong? Maybe.

To be fair, the seance has become a phenomenon far broader than that which Americans adapted from the European tradition. It is possible that I would have had more powerful experiences had I worked with Miss Cleo and her Voodoo faith or attended a Wiccan ceremony.

But consider this: For nearly 20 years, James Randi, the great-grandfather of professional skepticism, offered a prize of $1 million to any individual who could demonstrably prove "under proper observing conditions, evidence of any paranormal, supernatural or occult power."

The money went unclaimed.