Scientists Say Climate Change Could Render the Middle East Almost Uninhabitable by 2100

The moment you leave your air-conditioned home, the scalding heat will hit you as if you'd been sealed in an oven. Minutes later, your clothes will be soaked with sweat that hardly evaporates. Within six hours of continuous exposure, you'll lose consciousness and die.

This is the grim future of the Middle East, according to a new paper from Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Elfatih Eltahir and Loyola Marymount University environmental scientist Jeremy Pal published online this week in the journal Nature Climate Change.

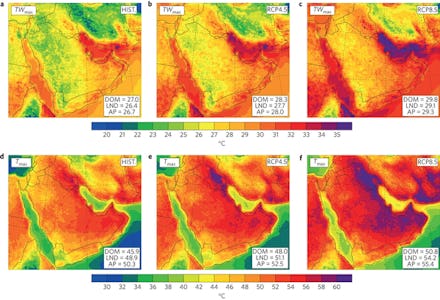

The two researchers concluded that if humans do not make serious changes to the way they are pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere by the end of the century, areas of the Persian Gulf region and wider Arab world could experience heat and humidity waves fundamentally hostile to human life.

Humans are capable of surviving in environments up to a "wet-bulb" temperature of 95 degrees Fahrenheit. (The "wet bulb" temperature is the lowest temperature that a warm object — like a human — can achieve via evaporative cooling — such as sweating, or being covered in water.)

Eltahir told the New York Times that 95 degree temperature translates to roughly 165 degrees Fahrenheit in a heat-index reading. When temperature and humidity combine to cross the 95 degrees Fahrenheit wet-bulb temperature, no amount of sweat will successfully cool off the human body.

In a statement on MIT's website, Eltahir explained their research predicted extreme temperatures that now currently happen once in every 20 summer days will become the norm. MIT wrote "major cities such as Doha, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, Dubai in the United Arab Emirates and Bandar Abbas, Iran," could be hitting the wet-bulb temperature "several times over a 30-year period" by the end of the century if CO2 emissions do not go down.

Heat waves that extreme could endanger the lives of anyone outdoors in the region, the authors writing that six hours of continuous exposure to a wet-bulb temperature of 95 degrees or higher would be enough to kill any human.

John P. Abraham, a thermal and fluid sciences expert at the University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, who studies the impact of heat on the human body, told Mic via email, "In order to survive very intense heat waves, you need to be properly hydrated and have a mechanism for cooling. So a way to adapt is to increase access to [air-conditioned] spaces. That is hard throughout the world.

"A second way is tried-and-true methods like full-body immersion in water," he added.

Clearly, a climate which requires either constant access to air conditioning or full-body water immersion to survive poses a major threat to the basic livability of the region. Workers preparing the 2022 World Cup facilities in Qatar, for example, are already at extreme risk of heat stroke under current environmental conditions. Meanwhile, some Arab countries are facing an imminent water crisis that is already a destabilizing influence.

A 2011 report by the World Food Program concluded "transitory weather shocks" like "drought and excess rainfall" contributed to rising food prices and the Arab Spring uprisings.

"There are already several areas in the Middle East that are uninhabitable, essentially desert, and those areas are apt to expand," Kevin Trenberth, a researcher for the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research, wrote to Mic. "Water availability will be a key."

Pennsylvania State University distinguished professor of meteorology Michael E. Mann told Mic via email that "there is uncertainty" in the authors' climate models, "but uncertainty typically hasn't been our friend."

"In many responses (the loss of Arctic sea ice, the decay of the ice sheets and rise in sea level), the impacts are happening faster than we originally predicted," Mann told Mic. "In this case, the only factor the authors are looking at is heat extremes. But there are other climate change-related threats, from worse drought to more powerful coastal storms to extreme flooding events and the increased spread of infectious disease, that pose a threat to habitability to many regions around the globe."

"Many of these threats are apparent now. We don't have to wait until the end of the century to see the negative impacts," Mann said.

A separate study released this year in Nature found evidence that global warming will result in massive economic damage to many of the world's economies, concluding that growth will decline in direct response to rising temperatures and that previous models significantly underestimated how bad the effects will be.

"The Earth has a big, hot band around the middle and small, cold polar caps, and more of us live in the warmer places," PSU geoscientist Richard Alley wrote to Mic. "Research has increasingly been showing that for growing many of our crops and working outside, most of us are at or a bit above the optimal temperature now.

"This new paper adds to the growing body of evidence that burning fossil fuels and releasing the CO2 to the air has costs from the resulting sea-level rise, changes in floods and droughts, ocean acidification and more, but that the warming itself can become very costly and dangerous," Alley said, "and that may grow to be the most important issue."