15 Years Ago, Outkast Made an Album So Good It Completely Rewrote the Rules of Hip-Hop

When Outkast first introduced audiences to Stankonia 15 years ago, the group made sure listeners knew exactly where they were. They were at "the center of the Earth, seven light-years below sea level," as Andre 3000 says in the opening words of the album — "the place from which all funky things come."

They were also in a studio in the Berkeley Park neighborhood of Atlanta, which Outkast had bought and named Stankonia shortly before beginning to record the album that would make the space legendary. More importantly, Stankonia was a place "where you can open yourself up and be free to express anything," Andre 3000 later said in an interview. It was here, careening between Atlanta and Atlantis, Outkast conceived an album that would change hip-hop forever.

The singles "Ms. Jackson" and "So Fresh, So Clean" are still irresistibly quotable. The deep cuts are still some of the most rewarding experimental hip-hop around. It was the album most hip-hop skeptics had to admit they liked. More than most other albums in the early '00s, Stankonia helped hip-hop build its foundation in the mainstream, where still it stands unfuckwithable today.

While proving how hook-y and marketable the genre could be, it gave the world a glimpse of how far the borders could expand. Spread across a tapestry of funk, psychedelic hard rock, gospel and jazz, Outkast's Stankonia proved hip-hop could outline spiritual conundrums just as effectively as it could describe the traps lining the edges of the ghetto. Music still feels the reverberations today.

Welcome to Stankonia. The album hit the shelves at a pivotal moment in Outkast's career. The duo were coming off a smash success with Aquemini, which had earned a perfect five-mic rating from the Source, the "bible of the genre," Creative Loafing notes. If Outkast wanted to surpass Aquemini with the next release, they knew they would need to reach beyond what hip-hop had attempted before.

"We're in the age of keeping it real, but we're trying to keep it surreal," Andre 3000 once said of the album's mission. He and Big Boi made a point of listening to no hip-hop while recording so as not to fall into any of the cliches they saw developing in the genre. Instead, they turned to Prince, George Clinton and Little Richard, but were careful not to go too deep. "I don't want this to be the generation that went back to '70s rock," Andre 3000 told Vibe. "You gotta take it and do new things with it."

The results are clear in "B.O.B," a searing fusion of Hendrix rock distortion and hyper-fast dancing breakbeats; "Humble Mumble," with its dreamy ballad piano lines floating over unrelenting syncopated snares and scratches; and the apocalyptic funk guitar work of "Gangsta Shit." Each beat is more experimental than the last, veering dangerously close to random at times, each another challenge to hip-hop to step its game up.

Finding that funk: The lyrics match the searching nature of the beats, with Andre 3000 and Big Boi's words narrating their quest for the funk. Said "funk," however, was a metaphor for so much more.

"I guess we're talking about an individual freedom," Andre 3000 told Fader. "Finding that gateway that opens you up, that frees you up mentally so you won't be stuck in a... a... I don't want to say a corporate mindstate, but more like a trained mindstate."

That search for freedom helped open up hip-hop for so many to follow. It gave those who worked on the album and in Atlanta's extended Dungeon Family scene an impeccable credential, helping launch the careers of Cee-Lo Green, Killer Mike and Future (cousin to Rico Wade, one of the producers in Organized Noise, responsible for three Stankonia tracks). Andre 3000 basically wrote the blueprint for the quirky genius in hip-hop, a model MCs like Young Thug to Kendrick Lamar are rewriting today.

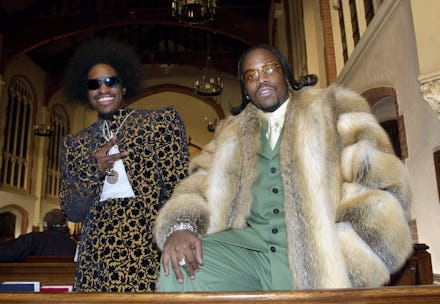

"Outkast has opened up so many doors, for not just for myself, but artists of color," Janelle Monáe, one of today's torch-bearers of the alternative hip-hop, said in an interview with Complex. "They basically rewrote how hip hop could sound, what it could look like, how we could dress, things we could say, the live instrumentation in music."

That freedom came with a bit of a price. The overwhelming creative energy the album barely managed to contain also likely sowed the seeds for the group's eventual dissolution. Listening to the album now, one can hear Andre 3000 and Big Boi's flows start to diverge into idiosyncratic territory: Andre's becoming more melodic, stream-of-consciousness and lyrical while Big Boi is growing more a more firm and confident Atlantan flex.

Even the way they describe the album's birthplace one can see the difference. "Stankonia is whatever's the funkiest shit ever," Big Boi told the Fader. "It could be that purple, or that funky-ass music." Compare it to Andre 3000's New Age, self-actualization explanation and once can see beginning of the fray.

The confidence in these new visions would eventually lead to the group splitting their efforts into Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, their next offering, essentially two solo efforts packaged as one. When they rejoined forces for 2006's Idlewild, the results were disappointing for those expecting that same uncontrollable chemistry.

Today, Big Boi is continuing the group's mission to channel the funk, while Andre 3000 has lost all inspiration to do anything music or Outkast-related. In a 2014 interview with Fader, he said he felt like a "sell-out" playing the hits they crafted on Stankonia during the group's recent reunion tour.

How one could feel like a sell-out screaming the "burn motherfucker, burn American dreams" of "Gasoline Dreams" to an audience of screaming fans is hard to imagine, but this is how the cracker crumbles. None of the group's present dysfunction changes how momentous it was when Outkast threw open the gates of Stankonia and welcomed the whole world to come and join. Hip-hop hasn't been the same since.