There's a Huge Advancement in Poop Science That Could Save Thousands of Lives

Clostridium difficile (C. diff) is a terrible way to die. It's an antibiotic-resistant gut bug that causes painful diarrhea, fever and kidney failure. Almost half a million Americans are diagnosed with C. diff a year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced in a February press release. Of those people, around 29,000 die within 30 days of diagnosis.

To put those numbers into perspective, here are a few more. In 2013, 32,719 people were killed in car crashes in the U.S., according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Every year, according to the CDC, 33,000 people are killed by guns in the U.S. This year, about 40,000 women in the U.S. are expected to die from breast cancer.

The intestinal infection comes from a spore-forming bacteria that neither soap nor alcohol can effectively kill and can live on surfaces for months. Though it's largely preventable with proper hygiene, it's usually spread in hospitals and nursing homes.

C. diff is generally treated in two ways: antibiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), also known as a fecal transplant — the "microbial equivalent of a blood transfusion," according to MinuteEarth. Doctors take a fecal sample from a healthy person and transplant it into the patient's intestines through a colonoscopy, enema or nasoenteric tube, which goes up the nose and down into the stomach. FMT is highly effective in treating C. diff cases when antibiotics fail, but it's an invasive procedure and is considered an experimental treatment. Currently, it's used only on patients for whom antibiotics have proven ineffective.

Now there's a much easier cure for this deadly infection: the poop pill.

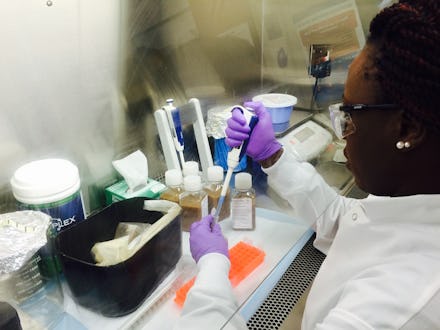

Inside the world's first poop lab

On Oct. 28, OpenBiome announced that it had started production of the first fecal transplant pill.

Even though FMT has been extremely successful for treating C. diff, it's still been difficult to make these transplants happen for people. That difficulty is what inspired Mark Smith to start OpenBiome, the world's first poop bank.

Since 2013, the Boston-based lab has been collecting healthy fecal matter, packaging it and sending it out to doctors around the world. Since then, OpenBiome has been involved in more than 7,500 treatments in roughly 460 hospitals, Carolyn Edelstein, OpenBiome's director of policy and global partnerships, told Mic.

"Despite the underlying simplicity and efficacy of FMT, prior to OpenBiome, it had become difficult for clinicians to offer FMT at a scale that matched patient needs because of the challenges of identifying and screening donors and processing stool material," OpenBiome's website says.

C. diff has traditionally been treated with antibiotics, and around 80% of C. diff patients will be cured by antibiotics, according to OpenBiome's clinical primer.

A study performed from 2008 to 2013 by the Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam tested the efficacy of FMT and antibiotics to treat C. diff. Researchers found that fecal transplants were far much more effective than antibiotics — so conclusively that they stopped the study early. Ninety-four percent of the participants who received FMT as treatment were cured, compared to 31% and 23% cured by different antibiotics.

The process of collecting, packaging and sending fecal matter to practitioners is pretty simple. First, the lab collects poop from donors in the area, then mixes it with saline and glycerol. After the solid is separated from the liquid, the liquid is put into bottles and frozen at minus 112 degrees before being sent to doctors via FedEx over dry ice.

The complicated part is choosing donors. For health and safety reasons, OpenBiome is extremely picky about who donates their poop. "It's harder to get into OpenBiome as a donor than it is to get into Princeton," Smith told Mic. The lab accepts poop from less than 3% of potential donors. Most of OpenBiome's donors are from nearby Tufts University.

Since the field is so new, Smith said, some fear that there are diseases we don't even know about yet that could be spread through FMT.

Now that the lab has cornered the market on FMT, OpenBiome is making the process a little easier to swallow by turning donated fecal matter into pills.

"It's harder to get into OpenBiome as a donor than it is to get into Princeton."

This latest advancement could change lives. Instead of a colonoscopy, enema or tube up the nose, C. diff can now be treated by swallowing a small capsule.

Yes, the pills are actually filled with poop. They contain essentially healthy fecal matter covered in an oil layer to protect the capsule, Edelstein said. Like the traditional FMT liquid, the pills are frozen to protect the bacteria.

You need a good sense of humor if you're going to work with poop all day. When Smith tells people about his line of work, "it usually leads to a very long conversation," he said. "It's very fun." People get excited about it — "maybe too excited about it," Smith continued. "People ask, 'What's it like to mail poo to strangers?'"

And yes, "poo" is what the folks at OpenBiome usually call it. "Poo is probably our most common descriptor," Smith said.

Saying that you work in a poop lab can confuse people, especially if you're at a loud party, Edelstein said. She's found some creative ways to describe what she does without having to bring poop into it. OpenBiome employees use lots of different "turdminology" — to quote OpenBiome's video — to describe their work.

"I generally stick with 'poo,' but 'stool' is popular," says lab technician Laura Burns in a video of lab processes OpenBiome provided to Mic. "Poop" is common too. "We have one girl on our team who calls it 'poo poo,'" Burns said.

Does anyone say "shit"? "Oh, yeah, all the time," said Burns. "Depends if they're happy or not happy in the moment."

The future of poop science

It's not all fun and poop puns at OpenBiome. The lab is changing the way we treat serious intestinal infections.

FMT is arguably the best alternative to antibiotic treatment for infections like C. diff. It's actually a little odd that C. diff is treated with antibiotics, because "almost all cases of C. diff are associated with antibiotic use," Smith told Mic.

"Imagine that there were terrorists on the loose in New York City, and we decided the way to deal with it was nuking New York." Smith said. "That's what antibiotics are like. C. diff is like a sleeper cell; it's waiting for a disturbance caused by antibiotics."

As antibiotics are used more regularly worldwide, there is a danger that we're creating more antibiotic-resistant bacteria like C. diff.

"There's a great effort to try to control the larger issue of antibiotic resistance, to the tune of involving the president," Dr. Cliff McDonald, a medical epidemiologist at the CDC, told Mic. "It's seen as a public health urgency to control this."

What's next: Now that the pill has been released, OpenBiome is setting its sights on more ways to use FMT.

"The two parallel efforts for the field I see are: finding new diseases that we can treat and improving the treatments that already work for some diseases and moving the treatment toward a more purified synthetic version," Smith said.

OpenBiome is trying to figure out the active ingredients that make FMT possible so they can grow them separately from a donor, Smith said.

"We're really excited about inflammatory bowel disease. There's some pretty interesting early data suggesting that FMT works for IBD," he said. "We're excited to figure out if it works and how it works."

"The pills could be good for long-term maintenance therapy," Smith said. "You don't want to get a colonoscopy every day." Instead, you could just take an FMT pill.