This Is How Payday Lenders Dodge Google, Target the Vulnerable and Exploit the Poor

When you're at your lowest, frightened of your debt, what disease you might have or how to handle feelings of panic or depression, there's one place you can go for answers that feels safe, like no one is watching and waiting to judge, scold or exploit you: Google.

But when you're looking at those search results — the pages and pages of potential answers — the watchful eyes of advertisers are looking back.

A new report from civil rights consulting firm Upturn shows how typing in a desperate query like "can't pay my rent" or "need help with car payments" can deliver you into the hands of payday lenders — exploitative loan services that seek out people in financial jeopardy and pull them into a vicious borrowing cycle with hidden fees and sky-high interest rates.

It's a system that finds people most vulnerable to financial crises and delivers them into fiscal ruin.

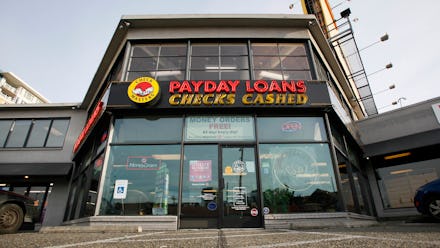

The online debt trap: Payday lending is a type of short-term loan that advertises fast cash you don't have to repay until your next check clears — so if you need money to immediately cover a medical bill and you're living paycheck to paycheck, it gives you fast access to money.

The trouble is that these loans come with enormous interest rates. Where a credit card has an annual percentage rate (APR) of 12%, a typical payday loan can come with hidden fees and APRs as high as 400% to 500%. Payday loan exploitation adversely affects minorities and the poor, and if you're in a position where you're vulnerable to financial dependency — say, if you're a victim of domestic abuse — payday loans can drive someone from dependency into emergency.

Over the past few years, payday lenders have been chased further out of the public eye, whether from government crackdowns or interventions from ad platforms like Google and Facebook. So that business (which was largely comprised of storefronts advertising rapid, same day payments) now does its business online through advertising. Even back in 2011, nine out of 10 complaints to the Better Business Bureau about payday loans involved online lenders.

But it's not the payday lenders themselves that are tucked away on the other end of your searchers — it's lead generators, where up to 75% of the online payday loan business comes from, according to the report.

Lead generators are simply middlemen who gather information about people looking for loans. Instead of an ad taking you to a site for payday loans, you'll see a form that asks if you'd like to provide your information and learn more. Then, the profiles of these financially desperate people are bundled and sold to payday lenders who don't have to get their hands dirty in advertising because middlemen are building lists of potential customers.

"If they get enough information, they can go to a data brokerage company to fill in the blanks," Aaron Rieke, director of tech policy projects at Upturn and co-author of the report, told Mic. "You'd think they'd have a good privacy policy, but none of these lead generation sites do. It's no exaggeration to say that they reserve themselves with unlimited right to do whatever they want with their data.

Finally, there is the potential coup de grâce in the repackaging of that information. Once people have put themselves in financial jeopardy, their personal information is valuable again to a whole new set of services. Legal services, financial recovery programs — the information of those loans' initial victims can be targeted a second time around, like dealers selling both a sickness and a cure.

Essentially, loans are being advertised, but not by the loaners. And because of this shell game, lead generators manage to evade bans and anti-payday loan policies, even as companies like Google try to swat their ads down, one by one.

Playing whack-a-mole: Google has a team that uses a combination of ad-flagging algorithms and actual humans to pick out malicious ads. Google told Mic that in 2014, it banned 214,000 bad actors who were not in compliance with their advertising policy (they couldn't provide numbers about how many of those were payday lenders).

Google doesn't outright ban payday loan advertising. Instead, the company has a strict policy that outlines what a loan service must have on its front page in order to advertise, like a clear description of their fees and what consequences someone faces for not paying.

"In 2012 we instituted new policies on short-term loans and we work hard to remove ads or advertisers that violate these policies," Google representative Crystal Dahlen told Mic. "If we become aware of any ads that violates our policies we immediately take action."

But Google's policies about who can advertise are largely based on state-by-state laws. In Vermont, for example, payday lending is outright banned, so Google does what it can to limit any ads served to people browsing in Vermont. As the Upturn report illustrates, out-of-state lenders still manage to find borrowers in these states.

Meanwhile, these ads are particularly high-value for Google. The average cost for these companies to buy your clicks is a couple of dollars, but Google can make as much as $8 to $12 for each ad clicked for online payday loans.

There's a simple, one-step solution: Google could simply ban anything resembling a payday loan. Facebook already does. Back in August, Facebook added a clause to their advertising policies banning any kind of ad for "payday loans, paycheck advances or any other short-term loan intended to cover someone's expenses until their next payday."

Rob Haralson is the executive director of Trust in Ads, the trade consortium of Google, Facebook, AOL, Yahoo and Twitter that helps those five Internet giants determine how to keep malicious advertisers away. Haralson's tentative defense for Google: The jury is still out between regulators over payday loans and their legality, though there may come a day when Google sees it in its best interest to lay down a systemic ban on these advertisers.

"If you look at weapons or cigarettes, they've made a conscious decision because it's what the company believes in," Haralson told Mic, with a reminder that Facebook's own stance is only a few months old. "This is one of countless topics and issues and areas these companies are looking at, and advertising policies are constantly scrutinized internally, tweaked and changed."

Until then, payday lenders are putting more layers of abstraction between themselves and anyone capable of reining them in.

"The large ad platforms are the first people to collect money when a consumer clicks on those ads," Rieke, who helped write the Upturn report, told Mic. "These platforms have, in the past, made decisions to protect their users from certain products and services. It's not enough to just say 'comply with the laws.'"