Everything I Know About Female Friendship I Learned From 'The Baby-Sitters Club'

I owned the entire Baby-Sitters Club collection growing up. Even the spinoffs. Even Karen's Haircut, the Baby-Sitters Little Sister book about Karen getting that disgusting mullet. My grandpa worked in the Scholastic factory, and he would bring me boxes of free books every time I saw him. After a few years, I had the kind of stockpile Matilda might have built up, if she hadn't had abusive parents.

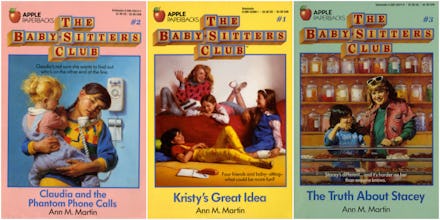

Although my mom begged me to give some away, I was desperate to keep every title of Ann M. Martin's series. The universe of Stoneybrook, Connecticut, the fictional town where the BSC was based, offered an exciting version of what my life might be like when I was one of "the big kids." For me, The Baby-sitters Club was nothing less than an instructional manual on how to navigate the world of female friendships.

When my neighbor Lisa and I stopped having much in common, for instance, I understood we could still be friends even if we didn't have many shared interests, as Kristy taught me when her friend Claudia started becoming interested in makeup and boys. And when my #1 BFF Stephanie committed the ultimate betrayal by making other BFFs at her new school, I understood that Stephanie could have multiple BFFs and still be important to me, just as Mary Anne realized she could be best friends with both Kristy and Dawn.

The 213 books in the series were an extended meditation on the moment in a young girl's life, when the things adults come to see as mundane — getting bad haircuts, receiving mysterious prank phone calls, having more than one BFF — feel major. Amid books about kids morphing into animals or haunted masks and dolls, stories about girls living independent lives and being empowered by friendship were the most thrilling stories on the shelf.

Ann M. Martin's Great Idea: The series began in 1986, when Scholastic editor Jean Feiwel saw that a book called Ginnie's Baby-Sitting Business was a top seller in the Arrow book club. (if you can take a second to imagine what procuring books was like before Amazon and Barnes & Noble, that was a monthly mailer from which students could order titles to be delivered to school.)

Despite its bland cover and page-four placement in the pamphlet, middle grade audiences (the term used to describe readers between the ages of 8 to 12) were consistently drawn to the title.

"I figured [the book's appeal] had to be about the baby-sitting," Feiwel told Mic. "What else could there be about the premise?"

She pitched Ann M. Martin the idea for The Baby-Sitters Club, knowing Martin was a smart, compassionate writer based on other hardcover children's titles she had done for Scholastic. Martin came back with a plan for four books, one from the perspective of each of the four main girls: Kristy, Mary Anne, Claudia and Stacey. Feiwel nixed the idea of Stacey's dad being involved in white-collar crime, otherwise allowing Martin the freedom to craft the concept for each of the main characters.

Seeing the success of the first four books, Scholastic cautiously requested two more, and two more after that, until The Baby-Sitters Club became the 12-book-a-year phenomenon it would be for the next decade and a half. As things continued taking off, Martin and Feiwel realized they had to freeze Stoneybrook in time. The books were coming out far too fast to continue aging their protagonists. Once the girls moved on to eighth grade, there they stayed, with one foot in childhood and one in adolescence for the remainder of the series.

That crystallized microcosm of adolescence is what made The Baby-Sitters Club so compelling. It has all the excitement of teenage maturity and independence, couched in the enthusiasm and innocence of childhood. In the first book, for instance, BSC president Kristy Thomas generates the idea for an intricate, under-the-table company, then yells, "Hooray!" when the school day is over and signals the entire business strategy to her best friend using only a flashlight.

"I think that this is a precious time in life," Feiwel said. "You experience and feel all the things that you will as you get older, but you have none of the real power that you do as you get older, or the real responsibility."

Kristy and the Teen Girl Entrepreneurs: At the heart of The Baby-sitters Club appeal was its narrative about preteen girls taking control of their own finances. That sense of agency and DIY entrepreneurship resonated with 8-to-12-year-old readers, who fantasized about being mature enough to start their own small businesses with their friends after school.

The fact that the girls were 13 was crucial to the appeal. "You're older than the little kids, but not yet a teen," said David Levithan, a Scholastic editor who started working on The Baby-Sitters Club as a 19-year-old intern and went on to edit the final 80 or 90 books. "You're not internalizing what the world is telling you to do," he added. "You're actually just doing what you want to do."

Since babysitting is a female-centric pursuit, Kristy and her cohorts had control of their insular girl world, a magical place in which boys (with the possible exception of Mary Anne's boyfriend Logan, who was introduced later in the series) are secondary characters at most.

"I wanted readers to be able to see girls as independent, as problem-solvers, as entrepreneurs," Martin told Mic, when asked why she kept the series so female-centric. "It sounds simple, but I really do believe this: that kids, girls, can become whatever they want to be."

And yet, what's even more important than that sense of entrepreneurship are the friendships forged within that space. It was crucial to Martin that she feature a wide range of girls, with varying backgrounds and family histories, to show them how to work through their differences and ultimately learn to prize sisterhood.

"From the beginning, I wanted to create a group of characters who were very different from one another, but who worked well together in spite of that and became close friends," she told Mic. That meant having racial diversity with the introduction of a Japanese-American character, Claudia and later, an African-American character, the ballerina Jessi. It also meant that the babysitters encountered a wide range of issues, such as dealing with divorce, growing up with a single parent or mourning the loss of a grandmother.

Claudia and the Terrifying Mysteries of Adolescence: Throughout the series, the baby sitters navigate haunted houses, learn sign language and get stranded on a desert island. But more often than not, the complexities of sisterhood drive the narrative. When the rest of the club has a fight in Mary Anne Saves The Day, for instance, Mary Anne has to overcome her signature shyness to bring the group back together. And in Stacey's Mistake, Stacey, a New York City transplant, must contend with the rivalry between her BSC best friends and her New York City best friends.

It all took place in the liminal space between being a child and being an adult, a time of adolescence when becoming a grown-up is too far away to be truly scary, but close enough to seem exciting. It's a moment in time when the bonds of friendship are crucial. In the books, friendship isn't just some happy side note in the girls' day-to-day lives, something the girls only pay lip service to when they're not fighting over boys and looking for dates to the school dance. Their friendships are entwined with who they are and who they will become.

"After this period, other relationships will take a little more importance or maybe primary importance," Feiwel said. "But, at that age, friendship is the thing, and I think that's a beautiful moment Ann was able to explore."

"Their friendships are entwined with who they are and who they will become."

Of course, part of the reason why the girls in The Babysitters' Club valued friendship so highly is because they were protected from the other complicated crap that happens during puberty. There was no sex or drugs in The Baby-Sitters Club, no Dawn's Pesky Pimple or Mallory Learns How to Use Super-Plus Tampons.

The breezy, G-rated tone of the books reads like an overly idealized depiction of adolescence (what self-respecting 13-year-old says "hooray!" at the end of a school day?), but it's also what makes it such an effective snapshot of adolescence: The girls are aware that they're teetering on the precipice of adulthood, but they don't quite know how to deal with that yet.

The approach of change is looming in Stoneybrook from Book #1. There's an awareness that high school will come along and threaten their idyllic arrangement gathered around a landline, waiting for the phone to ring.

As the president of the Baby-sitters Club who runs the organization with an iron fist, Kristy, a tomboy whose denial of her own adolescence is almost pathological, is the most obvious embodiment of this fear. She doesn't wear a bra, she's totally uninterested in boys or makeup, and she's also clear, time and again, that unlike the other club members, she has no interest in boys. "She's wearing a bra, and the way she talks, you'd think boys had just been invented," Kristy says describing Claudia in Kristy's Great Idea.

Kristy's rejection of boys, makeup and other signifiers of womanhood are intended as a reflection of her tomboyish personality. But they also represent an implicit awareness that things in her life will shift, no matter how forcefully she attempts to hold them in place. The subtext throughout the series is that she's afraid of the next step in growing up.

"Kristy can see that this is not going to last forever," Feiwel said. "That's why she's bossy about keeping everyone together and staying with the rules she's set. She would like things to stay the same in a way that's probably not so good, but that's what's sort of great about her as a character. She's not perfect and she'd like to control the world."

Kristy is able to control things, though, if only for a little while. She makes herself president of the Baby-sitters Club, keeping a firm grasp on all the comforts of childhood. But beyond the stories about dealing with a sick babysitting charge or competing with a rival teen babysitting agency lies a much more complicated reality. Life is going to get much, much harder. There are going to be icky things like tampons and lip gloss and sex, bigger complications that simply having great girlfriends won't fix.

Kristy held on to that moment in her life like I held on to every last copy of The Baby-Sitters Club, curled around a small stack, inviting my mother to pry them from my hands. But I eventually gave in to my mother's demands and gave away the books. I went on to middle school. By the time the series ended in 2000, Kristy, Claudia and the gang graduated from eighth grade and prepared to go to high school.

The Young Adult publishing world has changed dramatically since The Baby-sitters Club was first published nearly 30 years ago, thanks to the advent of the Internet and the massive hardcover success of Harry Potter. Yet the legacy of the series lives on. Those core principles of entrepreneurship and the value of female friendship live on for the 20-something and 30-something women who read the books as children, many of whom have reimagined the series set in the present-day. (One such series, 2014 Babysitters' Club Covers, imagines what it would be like if Mallory were on Tinder, or Kristy invested in Bitcoin.)

Martin told Mic that she regularly sees moms at her appearances, as well as a brand new group of 8-to-11-year-olds who are discovering the original series. The are also enjoying the graphic novel adaptations and the ebooks, and discovering themselves in her world. She's not sure exactly why the books are so timeless, but she has a hypothesis.

"I think the friendship aspect overrides any of the differences or things that might have made the books old-fashioned," Martin said. "I think we can get beyond all of those things because of the friendship especially."