The Exit Interview: Arne Duncan on His Legacy and the Future of Higher Education

Arne Duncan will go down as one of the most influential education secretaries in history.

Duncan, 51, will soon step down after serving for seven years as the United States secretary of education, making him one of President Barack Obama's longest-serving cabinet members and the second-longest-serving education secretary since the Department of Education was established in 1979.

During his time in office, Duncan has presided over an unprecedented growth of the size and scope of the federal government's role in K-12 education, enacting a $4.35 billion Race to the Top grant program that enticed states to enact a number of reforms, including performance-based pay for teachers and controversial Common Core standards for math and reading. On issues of higher education, Duncan's department has been similarly aggressive, overhauling the student loan industry, cracking down on for-profit colleges and combatting sexual assault on campus.

But that expansion of federal authority has come with its fair share of criticism, and Duncan is leaving office bruised by attacks from both the left and the right. In July 2014, delegates of the National Education Association, the largest teacher's union, called on Duncan to resign, citing his emphasis on school standards and standardized testing. Congress has taken steps to roll back many of the reforms Duncan has championed, and the House of Representatives recently voted to scale back the Education Department's authority over states and local school districts, with the Senate expected to do the same. On the campaign trail, Republican presidential candidates Sens. Marco Rubio of Florida and Rand Paul of Kentucky have called for eliminating the federal Education Department altogether.

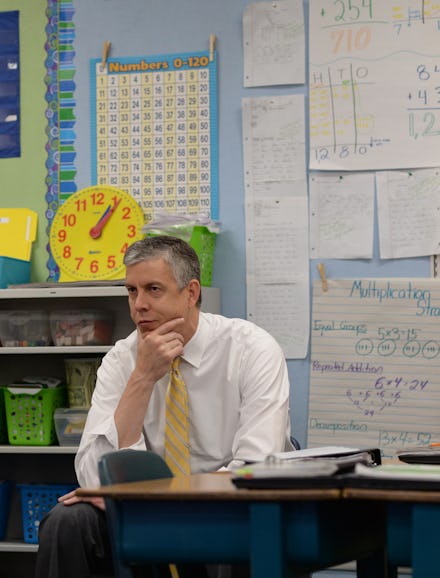

With the education secretary's legacy on the line, Mic sat down with Duncan in the department's offices in downtown Chicago on a recent Friday afternoon for a wide-ranging conversation to take stock of his record, particularly on issues related to higher education. At 6'5'', Duncan is a towering presence with a warm personality and tendency to speak frankly.

Although he said he is proud of his accomplishments while in office, Duncan also said he is leaving unsatisfied, with parts of his ambitious agenda stymied by partisan politics. He has a run-through-the-doors attitude and bristles at what he sees as the glacial pace of change in Washington.

Asked to grade himself on how he has handled higher education issues, Duncan's answer was telling: "Incomplete."

"There's still so much further to go," he said. "No one should be satisfied. Know that I'm not. I'm far from satisfied."

The background: Duncan grew up in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago's South Side. He graduated from Harvard University in 1987 and pursued a career as a professional basketball player with a four-year stint in Australia. In 1992, Duncan returned to Chicago to become the director of an education nonprofit focused on low-income students. It was during this time that he forged a unique bond with a little-known Illinois state senator named Barack Obama, a fellow hoops enthusiast. The two became close friends and regular partners in pick-up games.

Duncan was appointed CEO of Chicago Public Schools in 2001, a position he held until 2008. He said the experience profoundly shaped his view of the federal government's role in education.

"When I ran the Chicago public schools, the Department of Education was not always my friend," he said, recounting an episode in which he battled the department over cutting federal funding to an after-school tutoring program. "In fact, it rarely was. I went to Washington very skeptical about the federal government's role."

When Obama tapped Duncan as education secretary in 2008, Duncan suddenly found himself at the head of a department he had long viewed as unable or unwilling to pursue large-scale, meaningful change. But an influx of billions of dollars in education spending included in the stimulus package passed in 2009 gave Duncan unprecedented resources to implement reforms across the country.

He said that experience opened his eyes to what was possible with the resources and powers of the federal government at his disposal.

"Going in, if someone would have said, 'You can put $1 billion behind early childhood education. You can help encourage and incentivize 40-plus states to raise standards and think about setting assessments differently. You can put $40 billion into Pell grants without going back to taxpayers for a nickel,' I would've been like, 'I'm in! Can't be true,'" he said.

Early momentum eventually gave way to pitched battles over the department's newfound authority. Critics on the left and the right fault him for consolidating power over education policy in Washington, a criticism Duncan acknowledged, but flatly rejected.

"I think most of the critique we get is that we've done more than some folks would like," he said. "My dead honest critique of all of us, and I'll put myself at the top of the list, is we have not moved fast enough. There's a desperate need, and desperate urgency, and we don't act with that urgency."

On college debt: Duncan's track record on student loan debt has been mixed.

Duncan enjoyed several early successes aimed at combating the explosion of debt and containing the cost of college. His first victory was the implementation of an income-based repayment plan in 2009 to provide relief to students with large debt burdens. The program allows borrowers to recalculate their loan payments and pay a lower percentage of their income each month. Although the program has been criticized for its high cost to taxpayers, Duncan views it as one of his signature achievements.

"We've done a bunch to try to make loan repayments at the back end easier and cheaper, [including an] income-based and pay-as-you-earn [system] and loan forgiveness," Duncan said. "But having said that, [debt] is still a huge problem."

Another "leg in the stool" of higher education reform, as Duncan called it, was the 2010 overhaul of how the government provides student loans, quietly passed in tandem with the Affordable Care Act. The change eliminated the bank and lender-based student loan program that had existed for 45 years, making the Education Department the sole direct provider of federal student loans — a change Republicans characterized as a government takeover of the student loan market.

The law also increased funding for Pell Grants — direct federal assistance for low-income students — by $40 billion, an unprecedented expansion of the program and another of the accomplishments Duncan is most proud of.

"We went from 6 million Pell Grants to 9 million Pell Grants, a 50% increase," he said. "Many of those are helping first-generation college-goers. Since 2008, we have 1.1 million additional students of color going to college. That feels fantastic."

Duncan's final signature reform came earlier last year, when the Education Department released a report card system for colleges. The site, College Scorecard, publishes information about graduation rates, cost and the average salary of alumni at thousands of schools across the U.S. Duncan initially pushed to release a more robust scorecard that ranked colleges based on their value, but received staunch opposition from universities and the higher education lobby. The resulting version has been criticized for its complex methodology, but Duncan said it empowers students to make more informed decisions about where to go to college.

"We need to do a good job in not only helping young people choose good schools, but [also in selecting schools] where there are good graduation rates and the cost is reasonable," Duncan said.

Despite each of these changes, the scale of the problem remains staggering. Student debt has doubled from $666 billion to nearly $1.3 trillion during Duncan's time in office. States have dramatically cut funding for public colleges by an average of 19% since the Great Recession, and universities have jacked up tuition as a result. The total student loan debt in the U.S. now stands at $1.2 trillion, and 41 million Americans carry some form of student debt. One in five borrowers is either in default or struggling to make payments. So while Duncan was indeed able to secure higher funding for Pell Grants, the grant now covers the smallest percentage of the cost of attending school in 40 years, thanks to runaway tuition costs.

Duncan accepted part of the blame, but also noted that skyrocketing costs are, to some extent, beyond his control. "On the state level, the vast majority of states have disinvested," he said, referring to states who cut funding for higher education in the depths of the recession. "When they disinvest, what do universities do? They jack up the cost."

Duncan also said voters share a portion of the blame for electing politicians who have not made higher education a priority.

"I've never met a politician who didn't want to kiss babies and visit schools, but we as voters don't hold them accountable for actions," Duncan said. "We elect people who talk the talk and don't walk the walk."

On for-profit colleges: Another major focal point for Duncan's higher education agenda has been cracking down on predatory for-profit colleges.

Attendance at for-profit colleges had been on the rise prior to Duncan taking office, and continued to increase throughout the first several years of Obama's presidency. Hundreds of thousands of students took out federal loans to pay for degrees that in many cases proved worthless in the labor market. For-profit schools frequently engaged in deceptive or fraudulent marketing practices meant to entice as many students as possible to sign up, regardless of their ability to pay off student loans. Students at for-profit colleges constitute around 11% of borrowers, but make up 44% of all federal student loan defaults.

Consequently, Duncan's major emphasis has been implementing new gainful employment regulations on for-profit colleges and non-degree community colleges. The regulations are designed to hold these institutions accountable by ensuring they adequately prepared students for gainful job opportunities. The regulations survived a court challenge over the summer, a victory Duncan said was one of his hardest-fought but most important achievements.

"Probably one of the hardest battles I learned was the whole gainful employment thing," Duncan said. "We recently pushed through, but that was a years-long battle that I would have loved to have knocked out in year one and year two. That was painful and difficult."

Duncan also went after a number of large for-profit colleges head on, including the infamous Corinthian Colleges chain. Corinthian subsequently collapsed, and stocks at other colleges like the University of Phoenix have plummeted while enrollment is quickly declining.

In the wake of the Corinthian collapse, more than 1,000 students waged a debt strike to force Duncan's department to cancel their debts. After our interview, the department announced the cancellation of $28 million in student debt held by former Corinthian students.

But critics charge that the new process, which requires individuals to apply for relief, will leave many eligible former students out in the cold. The discharge will likely help just a tiny fraction of the estimated 125,000 students of students who are eligible for cancellation. Duncan has also been criticized for the department's slow response to the students' claims, a delay Duncan chalked up to the unprecedented nature of the situation. He said that the department had to invent a process for dealing with debt relief for students of for-profit colleges on the spot.

"We hadn't done this before. I think we had like six requests for debt relief, and now we're in the thousands," he said. "So it was a new world."

"We were absolutely learning as we went," Duncan said. "I'm sure it is slower than students would like, and I more than understand that if I were in their shoes. [But] I think we're getting to the right place."

On his legacy: Duncan, once skeptical about the federal government's ability to impact education, is leaving with the faith that change can indeed happen.

"I'm actually more hopeful and optimistic about what's possible," he said.

But much of Duncan's legacy hinges on whether the major reforms he championed in office can survive in Congress in the coming years — not to mention under the next president.

On the latter point, Duncan said he's been disappointed by the lack of discussion around education policy in the presidential campaign. Asked about the various candidates' positions on education policy, Duncan responded that those seeking the presidency should answer four key questions: "What's your commitment to early childhood education investment, and what resources are you going to put behind it? What's your goal to increase high school graduation rates? What's your goal to reduce dropout rates? And what's your goal to lead the world in college completion rate again?"

He was particularly frustrated with the lack of emphasis on education in the debates thus far.

"We've got a dozen people running for president, and I don't see anyone talking about those answers or asking those questions," he said. "Take the politics out. That's the conversation we need to have. Everything else to me is small ball."

Looking ahead, Duncan wouldn't share what he will do next, but said he has no plans to endorse any candidate for president or return to Washington to work in the next administration. He is, however, keen on continuing to have an impact.

"I want to see our country get better faster, and however it is, anyway I can be constructive and help, would love to do that," Duncan said, offering to do what he can to assist the next administration, no matter whose it is.

That is, with one exception. When the possibility of a Donald Trump presidency was raised, Duncan responded, "No comment," before catching himself. "No. Not Donald Trump."