It's Not Just Your Brain: This Is the Awful Toll Concussions Take on the Rest of Your Body

Concussions hurt. Slamming your head in a scrum, getting kicked in the face or just falling backward in a chair can cause some very real damage — even if it doesn't knock you out. Only 10% of concussions actually result in a blackout or unconsciousness, but the effects can take years, even decades, to rear their ugly head.

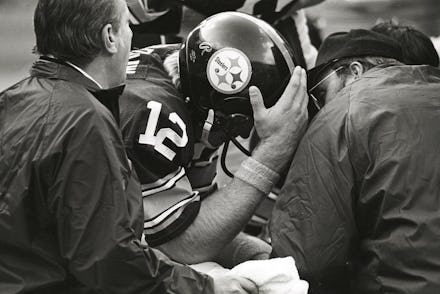

The new Will Smith movie Concussion follows a forensic pathologist named Dr. Bennet Omalu as he studies the death of former Steelers player Mike Webster. Omalu discovers a type of brain degeneration that works a lot like Alzheimer's disease. In the real-life case, Webster's doctors found that after repeated hits to his head, Webster suffered damage to his frontal lobe, which contributed to cognitive dysfunction, screwing up his attention span and concentration.

Other high-impact athletes have experienced even more extreme effects.

In 2005, Terry Long, an offensive lineman for the Steelers in the '80s and '90s, was found dead at 45 from drinking antifreeze. The next year, 44-year-old former Steelers and Cardinals safety Andre Waters shot himself in Tampa. In 2011, 50-year-old Dave Duerson, another safety, this time a former Bear, Giant and Cardinal, killed himself by shooting himself in the chest, complaining about a "deteriorating mental state."

In 2013, a hockey player and high school junior named Alexander Graham took his own life several months after being diagnosed with his first concussion. His parents said his attitude, usually upbeat, had turned depressive. The following year, another student athlete, a football player from Ohio State University named Kosta Karageorge, texted his mother to tell her concussions had messed up his head. Days later, he was found dead from a gunshot wound.

The list of former athletes who took their lives is much longer. Suicide has become a worrying potential byproduct of what's called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which is known for causing memory and cognition problems and a brain-damage grab bag of depression, suicidal behavior, poor impulse control, aggressiveness and dementia. On a more visible, physical level, the long-term effects of concussions can cause Parkinson's disease, leading to tremors, mobility issues and poor balance.

It goes deeper than headaches. Tau proteins are thought to act as "train tracks" in brain neurons that help the brain clean out toxic proteins. When the tau aren't working, those toxins can't get cleared, and you're left with a bunch of molecular-level crap keeping your brain from working at 100%.

With concussions, "you're seeing the tau proteins being laid down in excess, plus literal, degenerative-type changes at the brain level," Dr. Dennis Cardone, associate professor at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery in the Concussion Center at NYU Langone Medical Center, told Mic.

If the problems were only in athletes who get punched, kicked, or head-butted, it would be easier to track. But athletes who play contact sports aren't the only ones who slam their heads.

With concussions, more often than not, they aren't obvious — as in, if you don't black out, people think you're fine. "Ultimately, who's at risk for CTE is the part we don't understand well," Cardone told Mic. "A football player could take thousands of hits over a long career and have no problems 50 years down the road. But someone else hit with less force and fewer times could be the one who develops CTE. We just don't have good predictors for who it will be."

Right now, about 90% of concussions resolving within 10 to 14 days after impact. But that other 10% can last around six weeks. How treatment tends to work is having the patient check back in every couple weeks to see where the symptoms stand. But according to Cardone and Dr. Paul Testa, Chief Medical Info Officer at NYU Langone Medical Center, such spread-out treatment, especially if the patient's doctor can't ensure proper rest, might not be effective enough.

"Rest means a very different thing for me than it means for a varsity athlete midseason," Cardone told Mic. "Currently we recommend rest for a time, then you have a return-to-play algorithm. We used to say the same method for a heart attack. We know that's the wrong thing to do now."

Technology is filling an urgent need: A new app developed at NYU Langone called the NYU Langone Concussion Tracker App offers that granular, daily data to healthcare providers to make sure the patient is staying on course.

The app asks five questions daily and has patients rate their symptoms on a 1-to-5 scale. Since the app is also for wearable devices like the Apple Watch, there's a six-minute walking test to catch distance and heart rate, plus a concentration test, which has patients repeat strings of digits in reverse. "We can offer a clinician a visual representation of data that's a higher fidelity than waiting on a two-week checkup encounter," Testa told Mic.

Obviously most people won't download a concussion app just in case they might hit their heads. But extremely precise data like this could give medical professionals better understanding of how concussions work, how to prevent them — and, most important, how to help people spot them before it's too late.