The Big Problem With James Franco's Twitter Epic "Zola" Movie That Nobody Is Talking About

On Oct. 27, a 20-year-old Hooters waitress and part-time stripper named Aziah "Zola" Wells mesmerized the internet with an epic, 148-tweet retelling of her springtime trip from Detroit to Tampa.

During the trip, according to Zola's tweets, she was tricked by an acquaintance and fellow stripper named Jessica into a terrifying, multi-night caper filled with kidnapping, prostitution, coercion, rape and murder, all orchestrated by a brutal pimp referred to only as "Z."

The tale was so gripping and fueled by a disarming sense of gallows humor that it glued thousands of Twitter users to their screens. It wasn't long before rumors of a Hollywood adaptation started circulating — rumors that proved prophetic less than four months later.

"Okay listen up. This story long. So I met this white bitch at hooters." — Zola

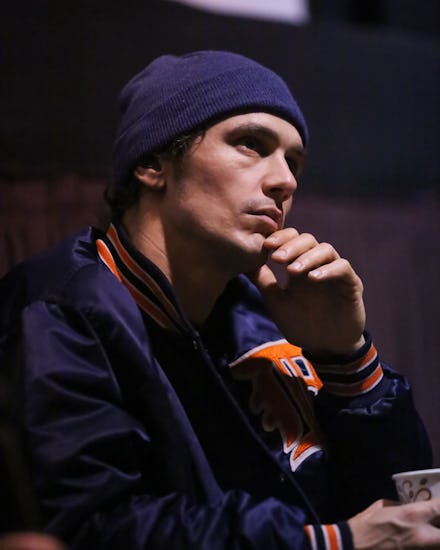

News broke Thursday that Zola's story would be adapted into a film directed by James Franco, a 37-year-old actor, filmmaker and white man best known for getting stuck between two rocks and selling $10,000 worth of "non-visible art."

Franco may be a talented director — I don't know, I've never seen any of his films. It does, however, seem worth remembering Franco's starring role in Spring Breakers — a film whose portrayal of black Florida amounted to a menacing safari for its white and Latina protagonists.

But his attachment to the Zola project speaks to how we're doing this "Hollywood diversity" conversation all wrong. It's not just about representation, like the boycotts and hashtags suggest. It's about economics. It's about who profits from intellectual labor and who doesn't.

Zola's story is the perfect example.

Consider this: By most metrics, Zola is part of multiple marginalized groups. She's black. She's a woman. If she's not a sex worker, she's at least directly peripheral to sex work and its perils. It's no secret why Zola's story has cinematic appeal: It's funny, suspenseful, full of social commentary and, as a bonus, it passes the Bechdel test. And now, a wealthy white man has been tapped to tell her story — not as a matter of charity, but to create a product for profit — at a time when a bevy of talented black woman filmmakers are making their voices known.

Not only is Franco telling Zola's story, he's "basing" his adaptation on the white male-authored Rolling Stone article about her, not Zola's direct account. The point isn't whether Franco can bring skill and sensitivity to this story. Nor is it about whether Zola is satisfied her story is being brought to the screen in the first place. It's about how even when stories about black women, told by black women and made popular by Black Twitter — a community dominated by black women — gain national attention, white men become the profiteers.

"So THE NEXT DAY I get a text like "BITCH LETS GO TO FLORIDA!" & I'm like huh???" — Zola

This may seem obvious: Opportunity in Hollywood boils down to who's collecting checks and who, which should surprise no one. But entertainment is funny that way. The industry's emphasis on profile and exposure — the finished product, as opposed to the process it takes to get there — makes it easy to mislead the discussion.

And the discussion is a rich one: In January, America learned for the second year in a row that all 20 of the Academy Awards' acting nominees were white. The wave of backlash that followed, from the #OscarsSoWhite hashtag to a full-on Oscar boycott initiated by black performers, made it clear that entertainers of color are tired — of both the lack of onscreen representation and not being recognized for their efforts when they are.

In many cases, as Janet Hubert pointed out in a viral tirade against Jada Pinkett Smith last month, these complaints are complicated by the fact they're being put forward by what amounts to the black Hollywood 1%: multi-millionaire performers arguing over trophies.

Meanwhile, the average black actor, writer or director can't even get a job in the industry or their films funded. But the entertainment industry is not a verdant field of opportunity. It's finite. There isn't room for everyone. A job given to a white man is a job not given to a black woman, and so on.

We also talk about diversity in terms of percentages: America is 17% Latino and 25% of movie-going audiences are Latino, so why aren't there more Latinos making movies?

"[After] making about $800, I was ready to go." — Zola

White perspectives dominate Hollywood. Inequality doesn't disappear when you start making money. And it does seem "fair," in an abstract sense, to have an entertainment industry that reflects the diversity of the American public.

But our desire for fairness seems to have been subsumed by a correlative amnesia: We've forgotten Hollywood isn't about fairness. It isn't about seeing faces like yours onscreen. It's about jobs, profit margins and the dollar value attached to intellectual and emotional work. And it's time to talk about it accordingly.

I'm reminded of white actor Michael Caine's response to the #OscarsSoWhite controversy: "Be patient," he said in a piece of advice to black actors. "Of course, it will come. Of course, it will come. It took me years to get an Oscar." But the hard truth is, such recognition is not nearly as guaranteed to creatives of color — nor is future employment.

At this point, our best hope for Zola is that she got a good lawyer to write her contract and her entertainment career doesn't end with a James Franco movie.